Reading: A New Civil Rights Movement

A New Civil Rights Movement

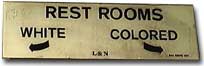

The Supreme Court's 1896 decision in Plessy v. Ferguson determined that "separate but equal" public facilities like restrooms and railroad cars were legal. The laws that resulted drove a further spike between the races in America.

In 1950, the United States operated under an apartheid-like system of legislated white supremacy.

Although the Civil War did bring an official end to slavery in the United States, it did not erase the social barriers built by that "PECULIAR INSTITUTION."

Despite the efforts of RADICAL RECONSTRUCTIONISTS, the American South emerged from the CIVIL WAR with a system of laws that undermined the freedom of African Americans and preserved many elements of white privilege. No major successful attack was launched on the segregation system until the 1950s.

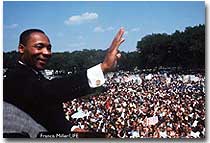

Martin Luther King Jr. addresses a crowd during the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in 1963.

Beginning with the Supreme Court's school integration ruling of 1954, the American legal system seemed sympathetic to African American demands that their FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT CIVIL RIGHTS be protected. Soon, a peaceful equality movement began under the unofficial leadership of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. A wave of marches, boycotts, sit-ins, and freedom rides swept the American South and even parts of the North.

Public opinion polls across the nation and the world revealed a great deal of sympathy for African Americans. The Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson administrations gave the Civil Rights Movement at least tacit support. Although many obstacles to complete racial equity remained, by 1965 most legal forms of discrimination had been abolished.

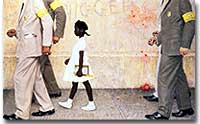

Through his paintings, Norman Rockwell challenged people to address the problem of racism in America. The Problem We All Live With, a work from the early days of desegregation, depicts a little girl being escorted to school by federal marshals.

Legal equality did not bring economic equality and social acceptance. Gains made by civil rights activists did not bring greater unity in the movement. On the contrary, as the 1960s progressed, a radical wing of the movement grew stronger and stronger. Influenced by Malcolm X, the Black Power Movement rejected the policy of nonviolence at all costs and even believed integration was not a desirable short-term goal. Black nationalists called for the establishment of a nation of African Americans dependent on each other for support without the interference or help of whites.

Race-related violence began to spread across the country. Beginning in 1964, a series of "long, hot summers" of rioting plagued urban centers. More and more individuals dedicated to African American causes became victims of assassination. Medgar Evers, Malcolm X, and Martin Luther King Jr. were a few of the more famous casualties of the tempest.

Hope and optimism gave way to alienation and despair as the 1970s began. Many realized that although changing racist laws was actually relatively simple, changing racist attitudes was a much more difficult task.

Separate No Longer?

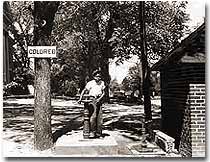

Jim Crow laws existed in several southern states and served to reinforce the white authority that had been lost following Reconstruction. One such law required blacks and whites to drink from separate water fountains.

During the first half of the 20th century, the United States existed as two nations in one.

The Supreme Court ruling in PLESSY V. FERGUSON (1896) decreed that the legislation of two separate societies — one black and one white — was permitted as long as the two were equal.

States across the North and South passed laws creating schools and public facilities for each race. These regulations, known as Jim Crow laws, reestablished white authority after it had diminished during the Reconstruction era. Across the land, blacks and whites dined at separate restaurants, bathed in separate swimming pools, and drank from separate water fountains.

The July 31, 1948, edition of theChicago Defender announces President Truman's executive order ending segregation in the U.S. armed forces.

The United States had established an American brand of apartheid.

In the aftermath of World War II, America sought to demonstrate to the world the merit of free democracies over communist dictatorships. But its segregation system exposed fundamental hypocrisy. Change began brewing in the late 1940s. President Harry Truman ordered the end of segregation in the armed services, andJACKIE ROBINSON became the first African American to play Major League Baseball. But the wall built by JIM CROW legislation seemed insurmountable.

The first major battleground was in the schools. It was very clear by mid-century that southern states had expertly enacted separate educational systems. These schools, however, were never equal. The NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE (NAACP), led by attorney THURGOOD MARSHALL, sued public schools across the South, insisting that the "SEPARATE BUT EQUAL" CLAUSE had been violated.

In the summer of 1947, Jackie Robinson became the first African American to play major league baseball. After a stellar career, he became the first African American player elected to the Baseball Hall of Fame.

In no state where distinct racial education laws existed was there equality in public spending. Teachers in white schools were paid better wages, school buildings for white students were maintained more carefully, and funds for educational materials flowed more liberally into white schools. States normally spent 10 to 20 times on the education of white students as they spent on African American students.

The Supreme Court finally decided to rule on this subject in 1954 in the landmarkBROWN V. BOARD OF EDUCATION OF TOPEKAcase.

The verdict was unanimous against segregation. "Separate facilities are inherently unequal," read Chief Justice EARL WARREN's opinion. Warren worked tirelessly to achieve a 9-0 ruling. He feared any dissent might provide a legal argument for the forces against integration. The united Supreme Court sent a clear message: schools had to integrate.

May 17, 1954, saw the Supreme Court — in the case of Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka — rule that segregation of public schools was a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment, which states that all citizens deserve equal protection under the law.

The North and the border states quickly complied with the ruling, but the Browndecision fell on deaf ears in the South. The Court had stopped short of insisting on immediate integration, instead asking local governments to proceed "with all deliberate speed" in complying.

Ten years after Brown, fewer than ten percent of Southern public schools had integrated. Some areas achieved a zero percent compliance rate. The ruling did not address separate restrooms, bus seats, or hotel rooms, so Jim Crow laws remained intact. But cautious first steps toward an equal society had been taken.

It would take a decade of protest, legislation, and bloodshed before America neared a truer equality.

Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott

Rosa Parks rode at the front of a Montgomery, Alabama, bus on the day the Supreme Court's ban on segregation of the city's buses took effect. A year earlier, she had been arrested for refusing to give up her seat on a bus.

On a cold December evening in 1955,ROSA PARKS quietly incited a revolution — by just sitting down.

She was tired after spending the day at work as a department store seamstress. She stepped onto the bus for the ride home and sat in the fifth row — the first row of the "COLORED SECTION."

In Montgomery, Alabama, when a bus became full, the seats nearer the front were given to white passengers.

Montgomery bus driver JAMES BLAKEordered Parks and three other African Americans seated nearby to move ("Move y'all, I want those two seats,") to the back of the bus.

Three riders complied; Parks did not.

The following excerpt of what happened next is from Douglas Brinkley's 2000 Rosa Park's biography.

|

"Are you going to stand up?" the driver demanded. Rosa Parks looked straight at him and said: "No." Flustered, and not quite sure what to do, Blake retorted, "Well, I'm going to have you arrested." And Parks, still sitting next to the window, replied softly, "You may do that." |

||

After Parks refused to move, she was arrested and fined $10. The chain of events triggered by her arrest changed the United States.

King, Abernathy, Boycott, and the SCLC

Martin Luther King Jr. organized the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955, which began a chain reaction of similar boycotts throughout the South. In 1956, the Supreme Court voted to end segregated busing.

In 1955, a little-known minister named MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. led the DEXTER AVENUE BAPTIST CHURCH in Montgomery.

Henry David Thoreau's work "Civil Disobedience" provided inspiration for many leaders of the Civil Rights Movement.

Born and educated in Atlanta, King studied the writings and practices of Henry David Thoreau andMOHANDAS GANDHI. Their teaching advocated civil disobedience and nonviolent resistance to social injustice.

A staunch devotee of nonviolence, King and his colleague RALPH ABERNATHY organized aBOYCOTT OF MONTGOMERY'S BUSES.

The demands they made were simple: Black passengers should be treated with courtesy. Seating should be allotted on a first-come-first-serve basis, with white passengers sitting from front to back and black passengers sitting from back to front. And African American drivers should drive routes that primarily serviced African Americans. On Monday, December 5, 1955 the boycott went into effect.

Don't Ride the Bus

In 1955, the Women's Political Council issued a leaflet calling for a boycott of Montgomery buses.

Don't ride the bus to work, to town, to school, or any place Monday, December 5.

Another Negro Woman has been arrested and put in jail because she refused to give up her bus seat.

Don't ride the buses to work to town, to school, or any where on Monday. If you work, take a cab, or share a ride, or walk.

Come to a mass meeting, Monday at 7:00 P.M. at the Holt Street Baptist Church for further instruction.

Montgomery officials stopped at nothing in attempting to sabotage the boycott. King and Abernathy were arrested. Violence began during the action and continued after its conclusion. Four churches — as well as the homes of King and Abernathy — were bombed. But the boycott continued.

Together with Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy (shown here) organized the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and helped lead the nonviolent struggle to overturn Jim Crow laws.

King and Abernathy's organization, theMONTGOMERY IMPROVEMENT ASSOCIATION (MIA), had hoped for a 50 percent support rate among African Americans. To their surprise and delight, 99 percent of the city's African Americans refused to ride the buses. People walked to work or rode their bikes, and carpools were established to help the elderly. The bus company suffered thousands of dollars in lost revenue.

Finally, on November 23, 1956, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the MIA. SEGREGATED BUSING was declared unconstitutional. City officials reluctantly agreed to comply with the Court Ruling. The black community of Montgomery had held firm in their resolve.

The Montgomery bus boycott triggered a firestorm in the South. Across the region, blacks resisted "moving to the back of the bus." Similar actions flared up in other cities. The boycott put Martin Luther King Jr. in the national spotlight. He became the acknowledged leader of the nascent CIVIL RIGHTS MOVEMENT.

With Ralph Abernathy, King formed the SOUTHERN CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE (SCLC).

This organization was dedicated to fighting Jim Crow segregation. African Americans boldly declared to the rest of the country that their movement would be peaceful, organized, and determined.

To modern eyes, getting a seat on a bus may not seem like a great feat. But in 1955, sitting down marked the first step in a revolution.

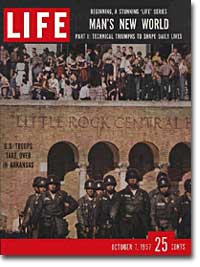

Showdown in Little Rock

President Eisenhower sent the 101st Airborne to Little Rock, Arkansas, to ensure the integration of Central High School in 1957.

Three years after the Supreme Court declared race-based segregation illegal, a military showdown took place in LITTLE ROCK, ARKANSAS. On September 3, 1957, nine black students attempted to attend the all-white Central High School.

Under the pretext of maintaining order, Arkansas Governor ORVAL FAUBUSmobilized the ARKANSAS NATIONAL GUARDto prevent the students, known as theLITTLE ROCK NINE, from entering the school. After a federal judge declared the action illegal, Faubus removed the troops. When the students tried to enter again on September 24, they were taken into the school through a back door. Word of this spread throughout the community, and a thousand irate citizens stormed the school grounds. The police desperately tried to keep the angry crowd under control as concerned onlookers whisked the students to safety.

The nation watched all of this on television. President Eisenhower was compelled to act.

To ensure their safety, African American students were escorted to Central High School in a U.S. Army car.

Eisenhower was not a strong proponent of civil rights. He feared that the Brown decision could lead to an impasse between the federal government and the states. Now that very stalemate had come. The rest of the country seemed to side with the black students, and the Arkansas state government was defying a federal decree. The situation hearkened back to the dangerous federal-state conflicts of the 19th century that followed the end of the Civil War.

On September 25, Eisenhower ordered the troops of the 101st Airborne Division into Little Rock, marking the first time United States troops were dispatched to the South since Reconstruction. He federalized the Arkansas National Guard in order to remove the soldiers from Faubus's control. For the next few months, the African American students attended school under armed supervision.

Can You Meet the Challenge?

This editorial by JANE EMERY appeared in Central High student newspaper, The Tiger, on September 19, 1957.

You are being watched! Today the world is watching you, the students of Central High. They want to know what your reactions, behavior, and impulses will be concerning a matter now before us. After all, as we see it, it settles now to a matter of interpretation of law and order.

Will you be stubborn, obstinate, or refuse to listen to both sides of the question? Will your knowledge of science help you determine your action or will you let customs, superstition, or tradition determine the decision for you?

This is the chance that the youth of America has been waiting for. Through an open mind, broad outlook, wise thinking, and a careful choice you can prove that America's youth has not "gone to the dogs" that their moral, spiritual, and educational standards are not being lowered.

This is the opportunity for you as citizens of Arkansas and students of Little Rock Central High to show the world that Arkansas is a progressive thriving state of wide-awake alert people. It is a state that is rapidly growing and improving its social, health, and educational facilities. That it is a state with friendly, happy, and conscientious citizens who love and cherish their freedom.

It has been said that life is just a chain of problems. If this is true, then this experience in making up your own mind and determining right from wrong will be of great value to you in life.

The challenge is yours, as future adults of America, to prove your maturity, intelligence, and ability to make decisions by how you react, behave, and conduct yourself in this controversial question. What is your answer to this challenge?

The following year, Little Rock officials closed the schools to prevent integration. But in 1959, the schools were open again. Both black and white children were in attendance.

The tide was slowly turning in favor of those advocating civil rights for African Americans. An astonished America watched footage of brutish, white southerners mercilessly harassing clean-cut, respectful African American children trying to get an education. Television swayed public opinion toward integration.

In 1959, Congress passed the CIVIL RIGHTS ACT, the first such measure since Reconstruction. The law created a permanent civil rights commission to assist black suffrage. The measure had little teeth and proved ineffective, but it paved the way for more powerful legislation in the years to come.

Buses and schools had come under attack. Next on the menu: a luncheonette counter.

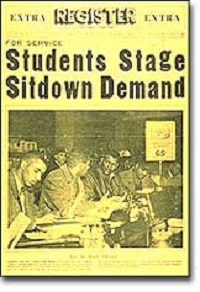

The Sit-In Movement

Students from across the country came together to form the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and organize sit-ins at counters throughout the South. This front page is from the North Carolina A&T University student newspaper.

By 1960, the Civil Rights Movement had gained strong momentum. The nonviolent measures employed by Martin Luther King Jr. helped African American activists win supporters across the country and throughout the world.

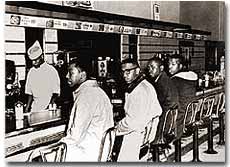

On February 1, 1960, a new tactic was added to the peaceful activists' strategy. Four African American college students walked up to a whites-only lunch counter at the localWOOLWORTH'S store in Greensboro, North Carolina, and asked for coffee. When service was refused, the students sat patiently. Despite threats and intimidation, the students sat quietly and waited to be served.

The civil rights sit-in was born.

No one participated in a sit-in of this sort without seriousness of purpose. The instructions were simple: sit quietly and wait to be served. Often the participants would be jeered and threatened by local customers. Sometimes they would be pelted with food or ketchup. Angry onlookers tried to provoke fights that never came. In the event of a physical attack, the student would curl up into a ball on the floor and take the punishment. Any violent reprisal would undermine the spirit of the sit-in. When the local police came to arrest the demonstrators, another line of students would take the vacated seats.

To challenge laws that kept interstate bus trips segregated, black and white students organized freedom rides through the South. The first such ride was interrupted when an angry mob attacked riders and destroyed their bus during a stop in Alabama.

SIT-IN organizers believed that if the violence were only on the part of the white community, the world would see the righteousness of their cause. Before the end of the school year, over 1500 black demonstrators were arrested. But their sacrifice brought results. Slowly, but surely, restaurants throughout the South began to abandon their policies of segregation.

In April 1960, Martin Luther King Jr. sponsored a conference to discuss strategy. Students from the North and the South came together and formed theSTUDENT NONVIOLENT COORDINATING COMMITTEE (SNCC). Early leaders included STOKELY CARMICHAEL and FANNIE LOU HAMER. The CONGRESS ON RACIAL EQUALITY (CORE) was a northern group of students led by JAMES FARMER, which also endorsed direct action. These groups became the grassroots organizers of future sit-ins at lunch counters, wade-ins at segregated swimming pools, and pray-ins at white-only churches.

By sitting in protest at an all-white lunch counter in Greensboro, North Carolina, four college students sparked national interest in the push for civil rights.

Bolstered by the success of direct action, CORE activists planned the first freedom ride in 1961. To challenge laws mandating segregated interstate transportation, busloads of integrated black and white students rode through the South. The first freedom riders left Washington, D.C., in May 1961 en route to New Orleans. Several participants were arrested in bus stations. When the buses reached Anniston, Alabama, an angry mob slashed the tires on one bus and set it aflame. The riders on the other bus were violently attacked, and the freedom riders had to complete their journey by plane.

New ATTORNEY GENERAL ROBERT KENNEDY ordered federal marshals to protect future freedom rides. Bowing to political and public pressure, the INTERSTATE COMMERCE COMMISSION soon banned segregation on interstate travel. Progress was slow indeed, but the wall between the races was gradually being eroded.

Gains and Pains

Over 250,000 individuals flooded Washington, D.C., in August 1963 to protest the treatment of African American citizens throughout the United States.

Civil rights activists in the early 1960s teemed with enthusiasm. The courts and the federal government seemed to be on their side, and the movement was winning the battle for public opinion. Under the protection of federal troops, in 1962 JAMES MEREDITH became the first African American to attend the UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI.

As sit-ins and freedom rides spread across the South, African American leaders set a new, ambitious goal: a federal law banning racial discrimination in all public accommodations and in employment. In the summer of 1963, President Kennedy indicated he would support such a measure, and thousands marched on Washington to support the bill.

Blacks and whites sang "WE SHALL OVERCOME" and listened to Martin Luther King Jr. deliver his "I HAVE A DREAM" speech. The Civil Rights Movement seemed on the brink of triumph.

As equality advocates notched more and more successes, the forces against change grew more active as well. Groups such the Ku Klux Klan increased hate crimes.

Earlier in 1963, the nation watched the Birmingham police force under the direction of BULL CONNOR unleash dogs, tear gas, and fire hoses on peaceful demonstrators.

16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, served as a meeting place for many participants of the civil rights movement. Tragedy struck the church in 1963 when a bomb exploded there, killing four young girls and injuring 22 others.

NAACP leader Medgar Evers was murdered in cold blood that summer in Mississippi as he tried to enter his home.

Church burnings and bombings increased. Four young girls were killed in one such bombing in Birmingham as they attended Sunday school lessons.

Many who had looked to JOHN F. KENNEDYas a sympathetic leader were crushed when he fell victim to assassination in November 1963. But Kennedy's death did not derail the Civil Rights Act.

PRESIDENT LYNDON JOHNSON signed the bill into law in July 1964. As of that day, it became illegal to refuse employment to an individual on the basis of race. Segregation at any public facility in America was now against the law.

Martin Luther King Jr. began his address at the March on Washington by saying "I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation."

The passage of that act led to a new focus. Many African Americans had been robbed of the right to vote since southern states enacted discriminatory poll taxes and literacy tests. Only five percent of African Americans eligible to vote were registered in Mississippi in 1965. The24TH AMENDMENT banned the POLL TAXin 1964. A new landmark law, theVOTING RIGHTS ACT of 1965, banned the literacy test and other such measures designed to keep blacks from voting. It also placed federal registrars in the South to ensure black suffrage. By 1965, few legal barriers to racial equality remained.

But centuries of racism could not be erased with the pen. Many African Americans continued to languish in the bottom economic strata. Civil rights activists fought on to achieve economic as well as legal equality. It is a fight that continues to this day.

In the words of Martin Luther King Jr.:

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal."I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia, the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slaveowners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a desert state, a state sweltering with the heat of injustice, a state sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

Full text of "I Have a Dream"

On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 people gathered in Washington, DC hoping to turn the nation's eyes to the problems of racial injustice and inequality. It was at this massive rally that Martin Luther King Jr. gave his best-known address. It has become known as the "I Have a Dream" speech.

On August 28, 1963, over 250,000 people gathered in Washington, DC hoping to turn the nation's eyes to the problems of racial injustice and inequality. It was at this massive rally that Martin Luther King Jr. gave his best-known address. It has become known as the "I Have a Dream" speech.

I am happy to join with you today in what will go down in history as the greatest demonstration for freedom in the history of our nation.

Fivescore years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand signed the Emancipation Proclamation. This momentous decree came as a great beacon light of hope to millions of Negro slaves who had been seared in the flames of withering injustice. It came as a joyous daybreak to end the long night of captivity.

But one hundred years later, we must face the tragic fact that the Negro is still not free. One hundred years later, the life of the Negro is still sadly crippled by the manacles of segregation and the chains of discrimination. One hundred years later, the Negro lives on a lonely island of poverty in the midst of a vast ocean of material prosperity. One hundred years later, the Negro is still languishing in the corners of American society and finds himself an exile in his own land. So we have come here today to dramatize a shameful condition.

In a sense we have come to our nation's capital to cash a check. When the architects of our republic wrote the magnificent words of the Constitution and the declaration of Independence, they were signing a promissory note to which every American was to fall heir. This note was a promise that all men would be guaranteed the "unalienable Rights of Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness." It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note insofar as her citizens of color are concerned. Instead of honoring this sacred obligation, America has given the Negro people a bad check which has come back marked "insufficient funds."

But we refuse to believe that the bank of justice is bankrupt. We refuse to believe that there are insufficient funds in the great vaults of opportunity of this nation. And we have come to cash this check, a check that will give us upon demand the riches of freedom and the security of justice.

We have also come to this hallowed spot to remind America of the fierce urgency of now. This is no time to engage in the luxury of cooling off or to take the tranquilizing drug of gradualism. Now is the time to rise from the dark and desolate valley of segregation to the sunlit path of racial justice. Now is the time to lift our nation from the quicksands of racial injustice to the solid rock of brotherhood. Now is the time to make justice a reality for all of God's children.

It would be fatal for the nation to overlook the urgency of the moment. This sweltering summer of the Negro's legitimate discontent will not pass until there is an invigorating autumn of freedom and equality. Nineteen sixty-three is not an end, but a beginning. And those who hope that the Negro needed to blow off steam and will now be content will have a rude awakening if the nation returns to business as usual. There will be neither rest nor tranquility in America until the Negro is granted his citizenship rights. The whirlwinds of revolt will continue to shake the foundations of our nation until the bright day of justice emerges.

But there is something that I must say to my people, who stand on the warm threshold which leads into the palace of justice: In the process of gaining our rightful place we must not be guilty of wrongful deeds. Let us not seek to satisfy our thirst for freedom by drinking from the cup of bitterness and hatred. We must forever conduct our struggle on the high plane of dignity and discipline. We must not allow our creative protest to degenerate into physical violence. Again and again, we must rise to the majestic heights of meeting physical force with soul force. The marvelous new militancy which has engulfed the Negro community must not lead us to distrust of all white people, for many of our white brothers, as evidenced by their presence here today, have come to realize that their destiny is tied up with our destiny. And they have come to realize that their freedom is inextricably bound to our freedom. We cannot walk alone.

And as we walk, we must make the pledge that we shall march ahead. We cannot turn back. There are those who are asking the devotees of civil rights, "When will you be satisfied?"

We can never be satisfied as long as the Negro is the victim of the unspeakable horrors of police brutality. We can never be satisfied as long as our bodies, heavy with the fatigue of travel, cannot gain lodging in the motels of the highways and the hotels of the cities. We cannot be satisfied as long as the Negro's basic mobility is from a smaller ghetto to a larger one. We can never be satisfied as long as our children are stripped of their selfhood and robbed of their dignity by signs stating "for whites only." We cannot be satisfied as long as a Negro in Mississippi cannot vote and a Negro in New York believes he has nothing for which to vote. No, no, we are not satisfied, and we will not be satisfied until "justice rolls down like waters and righteousness like a mighty stream."

I am not unmindful that some of you have come here out of great trials and tribulations. Some of you have come fresh from narrow jail cells. Some of you have come from areas where your quest for freedom left you battered by the storms of persecution and staggered by the winds of police brutality. You have been the veterans of creative suffering. Continue to work with the faith that unearned suffering is redemptive. Go back to Mississippi, go back to Alabama, go back to South Carolina, go back to Georgia, go back to Louisiana, go back to the slums and ghettos of our northern cities, knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed. Let us not wallow in the valley of despair.

I say to you today, my friends, so even though we face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.

I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: "We hold these truths to be self-evident: that all men are created equal."

I have a dream that one day on the red hills of Georgia the sons of former slaves and the sons of former slave owners will be able to sit down together at a table of brotherhood.

I have a dream that one day even the state of Mississippi, a desert state, sweltering with the heat of injustice, sweltering with the heat of oppression, will be transformed into an oasis of freedom and justice.

I have a dream that my four little children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day down in Alabama, with its vicious racists, with its governor having his lips dripping with the words of "interposition" and "nullification," one day right there in Alabama little black boys and black girls will be able to join hands with little white boys and white girls as sisters and brothers. I have a dream today.

I have a dream that one day "every valley shall be exalted, every hill and mountain shall be made low; the rough places will be made plain, and the crooked places will be made straight; and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed, and all flesh shall see it together."

This is our hope. This is the faith that I go back to the South with. With this faith we will be able to hew out of the mountain of despair a stone of hope. With this faith we will be able to transform the jangling discords of our nation into a beautiful symphony of brotherhood. With this faith we will be able to work together, to pray together, to struggle together, to go to jail together, to stand up for freedom together, knowing that we will be free one day. This will be the day when all of God's children will be able to sing with new meaning, "My country, 'tis of thee, sweet land of liberty, of thee I sing. Land where my fathers died, land of the pilgrim's pride, from every mountainside, let freedom ring."

And if America is to be a great nation this must become true.

So let freedom ring from the prodigious hilltops of New Hampshire.

Let freedom ring from the mighty mountains of New York.

Let freedom ring from the heightening Alleghenies of Pennsylvania!

Let freedom ring from the snowcapped Rockies of Colorado!

Let freedom ring from the curvaceous slopes of California!

But not only that; let freedom ring from Stone Mountain of Georgia!

Let freedom ring from Lookout Mountain of Tennessee!

Let freedom ring from every hill and every molehill of Mississippi.

From every mountainside, let freedom ring.

And when this happens, when we allow freedom ring, when we let it ring from every village and every hamlet, from every state and every city, we will be able to speed up that day when all of God's children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, "Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!"

Martin Luther King Jr.

As the leader of the nonviolent Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, Martin Luther King Jr. traversed the country in his quest for freedom. His involvement in the movement began during the bus boycotts of 1955 and was ended by an assassin's bullet in 1968.

As the unquestioned leader of the peaceful Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING JR. was at the same time one of the most beloved and one of the most hated men of his time. From his involvement in the Montgomery bus boycott in 1955 until his untimely death in 1968, King's message of change through peaceful means added to the movement's numbers and gave it its moral strength. The legacy of Martin Luther King Jr. is embodied in these two simple words: equality and nonviolence.

King was raised in an activist family. His father was deeply influenced by MARCUS GARVEY's BACK TO AFRICA MOVEMENT in the 1920s. His mother was the daughter of one of Atlanta's most influential African American ministers. As a student, King excelled. He easily moved through grade levels and entered Morehouse College, his father's alma mater, at the age of fifteen. Next, he attended Crozer Theological Seminary, where he received a Bachelor of Divinity degree. While he was pursuing his doctorate at Boston University, he met and married CORETTA SCOTT. After receiving his Ph.D. in 1955, King accepted an appointment to the Dexter Street Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama.

Birmingham, Alabama, police commissioner Bull Connor ordered that fire hoses and dogs be used to subdue protesters. The violence that ensued was broadcast across the nation galvanized the Civil Rights Movement.

After his organization of the bus boycott, King formed the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which dedicated itself to the advancement of rights for African Americans. In April 1963, King organized a protest in Birmingham, Alabama, a city King called "the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States." Since the end of World War II, there had been 60 unsolved bombings of African American churches and homes.

Boycotts, sit-ins and marches were conducted. When Bull Connor, head of the Birmingham police department, used fire hoses and dogs on the demonstrators, millions saw the images on television. King was arrested. But support came from around the nation and the world for King and his family. Later in 1963, he delivered his famous "I Have a Dream" speech to thousands in Washington, D.C.

In March 1965, Dr. King led protestors on a 50-mile, voting-rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. It took three attempts for the protestors to complete the march, battling tear gas, cattle prods, and police batons, but the national attention drawn by their efforts ultimately led to the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

After the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, King turned his efforts to registering African American voters in the South. In 1965, he led a march in Selma, Alabama, to increase the percentage of African American voters in Alabama. Again, King was arrested. Again, the marchers faced attacks by the police. Tear gas, cattle prods, and billy clubs fell on the peaceful demonstrators. Public opinion weighed predominantly on the side of King and the protesters. Finally, President Johnson ordered the National Guard to protect the demonstrators from attack, and King was able to complete the long march from Selma to the state capital of Montgomery. The action in Selma led to the passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

Early in the morning of April 4, 1968, King was shot by JAMES EARL RAY. Spontaneous violence spread through urban areas as mourners unleashed their rage at the loss of their leader. Rioting burst forth in many American cities.

RFK on MLK

The day Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, Robert F. Kennedy was campaigning for the presidency in Indianapolis, Indiana. Kennedy made this speech in remembrance of Dr. King's tireless efforts.

I have bad news for you, for all of our fellow citizens, and people who love peace all over the world, and that is that Martin Luther King was shot and killed tonight.

Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and to justice for his fellow human beings, and he died because of that effort.

In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in. For those of you who are black — considering the evidence there evidently is that there were white people who were responsible — you can be filled with bitterness, with hatred, and a desire for revenge. We can move in that direction as a country, in great polarization — black people amongst black, white people amongst white, filled with hatred toward one another.

Or we can make an effort, as Martin Luther King did, to understand and to comprehend, and to replace that violence, that stain of bloodshed that has spread across our land, with an effort to understand with compassion and love.

For those of you who are black and are tempted to be filled with hatred and distrust at the injustice of such an act, against all white people, I can only say that I feel in my own heart the same kind of feeling. I had a member of my family killed, but he was killed by a white man. But we have to make an effort in the United States, we have to make an effort to understand, to go beyond these rather difficult times.

My favorite poet was Aeschylus. He wrote: "In our sleep, pain which cannot forget falls drop by drop upon the heart until, in our own despair, against our will, comes wisdom through the awful grace of God."

What we need in the United States is not division; what we need in the United States is not hatred; what we need in the United States is not violence or lawlessness; but love and wisdom, and compassion toward one another, and a feeling of justice toward those who still suffer within our country, whether they be white or they be black.

So I shall ask you tonight to return home, to say a prayer for the family of Martin Luther King, that's true, but more importantly to say a prayer for our own country, which all of us love — a prayer for understanding and that compassion of which I spoke.

We can do well in this country. We will have difficult times; we've had difficult times in the past; we will have difficult times in the future. It is not the end of violence; it is not the end of lawlessness; it is not the end of disorder.

But the vast majority of white people and the vast majority of black people in this country want to live together, want to improve the quality of our life, and want justice for all human beings who abide in our land.

Let us dedicate to ourselves to what the Greeks wrote so many years ago: to tame the savageness of man and make gentle the life of this world.

Let us dedicate ourselves to that, and say a prayer for our country and for our people.

But the world never forgot his contributions. Time magazine had named him "Man of the Year" in 1963. In 1964, he won the Nobel Peace Prize and was described as "the first person in the Western world to have shown us that a struggle can be waged without violence." In 1977, he was posthumously awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest award a civilian American can earn. In the 1980s, his birthday became a national holiday, creating an annual opportunity for Americans to reflect on the two values he dedicated his life to advancing: equality and nonviolence.

The Long, Hot Summers

Nearly 4000 people were arrested for various crimes, including looting, during the Watts riots of the 1960s.

On August 11, 1965, the atmosphere in the WATTS district of Los Angeles turned white hot. A police patrol stoppedMARQUETTE FRYE, suspecting he was driving while intoxicated. A crowd assembled as Frye was asked to step out of his vehicle. When the arresting officer drew his gun, the crowd erupted in a spontaneous burst of anger.

Too many times had the local citizens of Watts felt that the police department treated them with excessive force. They were tired of being turned down for jobs in Watts by white employers who lived in wealthier neighborhoods. They were troubled by the overcrowded living conditions in rundown apartments. The Frye incident was the match that lit their fire. His arrest prompted five days of rioting, looting, and burning. The governor of California ordered the National Guard to maintain order. When the smoke cleared, 34 people were killed and property damage estimates approached $40 million.

The National Guard was dispatched to Los Angeles to help quell the rioting plaguing the Watts section of the city. Here, a Guardsman helps a woman safely cross the street.

The urban uprising, part of what was often called "THE LONG, HOT SUMMER," had actually begun in 1964. When a white policeman in Harlem shot a black youth in July 1964, a similar disturbance flared (though on a lesser scale than the Watt's riots.) Rochester, Jersey City, and Philadelphia exploded as well. From 1964 to 1966, outbreaks of violence rippled across many other northern urban areas, including Detroit, where 43 people were killed.

As youths of the counterculture celebrated the famed Summer of Love in 1967, serious racial upheaval took place in more than 150 American cities. The assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 touched off a wave of violence in 125 more urban centers.

A quarter century after the Watts riots, a bystander took a video of white Los Angeles police officers beating Rodney King, a black suspect. The event triggered a riot in L.A. that lasted six days.

At the behest of President Johnson, theKERNER COMMISSION was created to examine the causes behind the rioting. After a six-month study, the committee declared that the source of unrest was white racism. Despite legislative gains against discriminatory policies, America was moving toward two distinct societies divided along racial lines.

As the great migration of blacks from the South to northern cities continued, white northerners began deserting the cities for the suburbs.

African Americans had been victimized by poor education, the unavailability of quality employment, slum conditions, and police brutality. The average income of a black household was only slightly more than half the income of its white counterpart. The Kerner Commission recommended a wide array of social spending programs, including housing programs, job training, and welfare. Civil rights legislation became the cornerstone of Lyndon Johnson's GREAT SOCIETY PROGRAM.

Malcolm X and the Nation of Islam

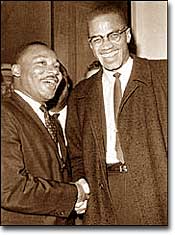

Though Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X were both influential figures in the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, the two met only once and exchanged just a few words.

When MALCOLM LITTLE was growing up in Lansing, Michigan, he developed a mistrust for white Americans. Ku Klux Klan terrorists burned his house, and his father was later murdered — an act young Malcolm attributed to local whites. After moving to Harlem, Malcolm turned to crime. Soon he was arrested and sent to jail.

The prison experience was eye-opening for the young man, and he soon made some decisions that altered the course of his life. He began to read and educate himself. Influenced by other inmates, he converted to Islam. Upon his release, he was a changed man with a new identity.

Believing his true lineage to be lost when his ancestors were forced into slavery, he took the last name of a variable: X.

Malcolm X was a practitioner of the Black Muslim faith, which combines the religious aspects of Islam with the ideas of both black power and black nationalism.

WALLACE FARD founded the NATION OF ISLAM in the 1930s. Christianity was the white man's religion, declared Fard. It was forced on African Americans during the slave experience. Islam was closer to African roots and identity. Members of the Nation of Islam read the Koran, worship Allah as their God, and accept Mohammed as their chief prophet. Mixed with the religious tenets of Islam were BLACK PRIDEand BLACK NATIONALISM. The followers of Fard became known as BLACK MUSLIMS.

When Fard mysteriously disappeared,ELIJAH MUHAMMAD became the leader of the movement. The Nation of Islam attracted many followers, especially in prisons, where lost African Americans most looked for guidance. They preached adherence to a strict moral code and reliance on other African Americans. Integration was not a goal. Rather, the Nation of Islam wanted blacks to set up their own schools, churches, and support networks. When Malcolm X made his personal conversion, Elijah Muhammad soon recognized his talents and made him a leading spokesperson for the Black Muslims.

Martin and Malcolm

Although their philosophies may have differed radically, Malcolm X believed that he and Martin Luther King Jr. were working toward the same goal and that given the state of race relations in the 1960s, both would most likely meet a fatal end. This excerpt is taken from THE AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF MALCOLM X, which was cowritten with famed ROOTSauthor ALEX HALEY.

The goal has always been the same, with the approaches to it as different as mine and Dr. Martin Luther King's non-violent marching, that dramatizes the brutality and the evil of the white man against defenseless blacks. And in the racial climate of this country today, it is anybody's guess which of the "extremes" in approach to the black man's problems might personally meet a fatal catastrophe first — "non-violent" Dr. King, or so-called '"violent" me.

As Martin Luther King preached his gospel of peaceful change and integration in the late 1950s and early 1960s, Malcolm X delivered a different message: whites were not to be trusted. He called on African Americans to be proud of their heritage and to set up strong communities without the help of white Americans. He promoted the establishment of a separate state for African Americans in which they could rely on themselves to provide solutions to their own problems. Violence was not the only answer, but violence was justified in self-defense. Blacks should achieve what was rightfully theirs "by any means necessary."

Cartoonist Jimmy Margulies's satire of police profiling — the practice of pulling motorists over simply because of their race — won him an award for excellence in journalism. Caption: "Not only does this have dynamic performance, but think of the oohs and aahs you'll get when you're pulled over on the turnpike."

Malcolm X electrified urban audiences with his eloquent prose and inspirational style. In 1963, he split with the Nation of Islam; in 1964, he made the pilgrimage to Mecca. Later that year, he showed signs of softening his stand on violence and even met with Martin Luther King Jr. to exchange remarks. What direction he might have ultimately taken is lost to a history that can never be written. As Malcolm X led a mass rally in Harlem on February 21, 1965, rival Black Muslims gunned him down.

Although his life was ended, the ideas he preached lived on in the Black Power Movement.

Black Power

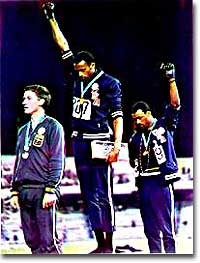

During the October 16, 1968 awards ceremony at the Mexico City Olympics, U.S. gold and bronze medallists John Carlos and Tommie Smith raise their arms and fists in a Black Power salute.

On June 5, 1966, JAMES MEREDITH was shot in an ambush as he attempted to complete a peaceful march from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi. Meredith had already made national headlines in 1962 by becoming the first African American to enroll at the University of Mississippi.

Civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., FLOYD MCKISSICK of CORE, and Stokely Carmichael of SNCC rushed to Meredith's hospital bed. They determined that his march must be completed. As Carmichael and McKissick walked through Mississippi, they observed that little had changed despite federal legislation. Local townspeople harassed the marchers while the police turned a blind eye or arrested the activists as troublemakers.

The "Black Panther Party for Self Defense" was formed to protect Black individuals and neighborhoods from police brutality. This 1966 photo features the six original members of the Black Panthers.

At a mass rally, Carmichael uttered the simple statement: "What we need is black power." Crowds chanted the phrase as a slogan, and a movement began to flower.

Carmichael and McKissick were heavily influenced by the words of Malcolm X, and rejected integration as a short-term goal. Carmichael felt that blacks needed to feel a sense of racial pride and self-respect before any meaningful gains could be achieved. He encouraged the strengthening of African American communities without the help of whites.

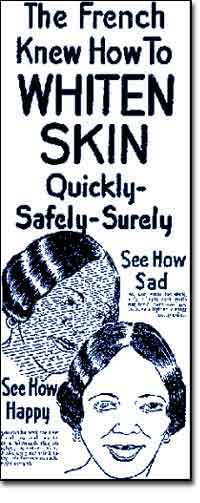

The Black Power movement turned popular fashion and aesthetics on end. In the 1930s, skin lighteners and hair straighteners were used by fashionable black women in an effort to look whiter. By the end of the 1960s, being proud of the African heritage dictated that afros and dark skin were desirable.

Chapters of SNCC and CORE — both integrated organizations — began to reject white membership as Carmichael abandoned peaceful resistance. Martin Luther King Jr. and the NAACP denounced black power as the proper forward path. But black power was a powerful message in the streets of urban America, where resentment boiled and tempers flared.

Soon, African American students began to celebrate African American culture boldly and publicly. Colleges teemed with young blacks wearing traditional African colors and clothes. Soul singer JAMES BROWN had his audience chanting "Say it loud, I'm black and I'm proud." Hairstyles unique to African Americans became popular and youths proclaimed, "BLACK IS BEAUTIFUL!"

That same year, HUEY NEWTON AND BOBBY SEALE took Carmichael's advice one step further. They formed the BLACK PANTHER PARTY in Oakland, California. Openly brandishing weapons, the Panthers decided to take control of their own neighborhoods to aid their communities and to resist police brutality. Soon the Panthers spread across the nation. The Black Panther Party borrowed many tenets from socialist movements, including Mao Zedong's famous creed "Political power comes through the barrel of a gun." The Panthers and the police exchanged gunshots on American streets as white Americans viewed the growing militancy with increasing alarm.

Black Panther Party

In 1966, the Black Panther Party offered a list of their wants and beliefs. Drawing from the language of the Declaration of Independence, the document made a powerful statement about the state of race relations in the United States at the time.

THE BLACK PANTHER PARTY

Platform & Program

October 1966

WHAT WE WANT

WHAT WE BELIEVE

1. WE WANT freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.

WE BELIEVE that black people will not be free until we are able to determine our destiny.

2. WE WANT full employment for our people.

WE BELIEVE that the federal government is responsible and obligated to give every man employment or a guaranteed income. We believe that if the white American businessmen will not give full employment, then the means of production should be taken from the businessmen and placed in the community so that the people of the community can organize and employ all of its people and give a high standard of living.

3. WE WANT an end to the robbery by the CAPITALIST of our Black Community.

WE BELIEVE that this racist government has robbed us and now we are demanding the overdue debt of forty acres and two mules. Forty acres and two mules was promised 100 years ago as restitution for slave labor and mass murder of black people. We will accept the payment in currency which will be distributed to our many communities. The Germans are now aiding the Jews in Israel for the genocide of the Jewish people. The Germans murdered six million Jews. The American racist has taken part in the slaughter of over fifty million black people; therefore, we feel that this is a modest demand that we make.

4. WE WANT decent housing, fit for the shelter of human beings.

WE BELIEVE that if the white landlords will not give decent housing to our black community, then the housing and the land should be made into cooperatives so that our community, with government aid, can build and make decent housing for its people.

5. WE WANT education for our people that exposes the true nature of this decadent American society. We want education that teaches us our true history and our role in the present-day society.

WE BELIEVE in an educational system that will give to our people a knowledge of self. If a man does nothave knowledge of himself and his position in society and the world, then he has little chance to relate to anything else.

6. WE WANT all black men to be exempt from military service.

WE BELIEVE that Black people should not be forced to fight in the military service to defend a racist government that does not protect us. We will not fight and kill other people of color in the world who, like black people, are being victimized by the white racist government of America. We will protect ourselves from the force and violence of the racist police and the racist military, by whatever means necessary.

7. WE WANT an immediate end to POLICE BRUTALITY and MURDER of black people.

WE BELIEVE we can end police brutality in our black community by organizing black self-defense groups that are dedicated to defending our black community from racist police oppression and brutality. The Second Amendment to the Constitution of the United States gives a right to bear arms. We therefore believe that all black people should arm themselves for self- defense.

8. WE WANT freedom for all black men held in federal, state, county and city prisons and jails.

WE BELIEVE that all black people should be released from the many jails and prisons because they have not received a fair and impartial trial.

9. WE WANT all black people when brought to trial to be tried in court by a jury of their peer group or people from their black communities, as defined by the Constitution of the United States.

WE BELIEVE that the courts should follow the United States Constitution so that black people will receive fair trials. The 14th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution gives a man a right to be tried by his peer group. A peer is a person from a similar economic, social, religious, geographical, environmental, historical and racial background. To do this the court will be forced to select a jury from the black community from which the black defendant came. We have been, and are being tried by all-white juries that have no understanding of the "average reasoning man" of the black community.

10. WE WANT land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice and peace. And as our major political objective, a United Nations supervised plebiscite to be held throughout the black colony in which only black colonial subjects will be allowed to participate, for the purpose of determining the will of black people as to their national destiny.

WHEN, in the course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bonds which have connected them with another, and to assume, among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the laws of nature and nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

WE HOLD these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. **That, to secure these rights, governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that, whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute a new government, laying its foundation on such principles, and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their safety and happiness.** Prudence, indeed, will dictate that governments long established should not be changed for light and transient causes; and, accordingly, all experience hath shown, that mankind are more disposed to suffer, while evils are sufferable, than to right themselves by abolishing the forms to which they are accustomed. **But, when a long train of abuses and usurpations, pursuing invariably the same object, evinces a design to reduce them under absolute despotism, it is their right, it is their duty, to throw off such government, and to provide new guards for their future security.

The peaceful Civil Rights Movement was dealt a severe blow in the spring of 1968. On the morning of April 4, King was gunned down by a white assassin named James Earl Ray. Riots spread through American cities as African Americans mourned the death of their most revered leader. Black power advocates saw the murder as another sign that white power must be met with similar force. As the decade came to a close, there were few remaining examples of legal discrimination. But across the land, de facto segregation loomed large. Many schools were hardly integrated and African Americans struggled to claim their fair share of the economic pie.