Reading: Economy

History

As long as someone has been making and distributing goods or services, there has been some sort of economy; economies grew larger as societies grew and became more complex. The ancient economy was mainly based on subsistence farming. According to Herodotus, and most modern scholars, the Lydians were the first people to introduce the use of gold and silver coin.[1] It is thought that these first stamped coins were minted around 650-600 BC.[2]

For most people the exchange of goods occurred through social relationships. There were also traders who bartered in the marketplaces. The Babylonians and their city state neighbors developed economic ideas comparable to those employed today.[3] They developed the first known codified legal and administrative systems, complete with courts, jails, and government records.[4]

About 2600 BC the use of writing expanded beyond debt/payment certificates and inventory lists to be applied for the first time to messages and mail delivery, history, legend, mathematics, and astronomical records. Ways to divide private property, when it is contended, amounts of interest on debt, rules as to property and monetary compensation concerning property damage or physical damage to a person, fines for 'wrong doing', and compensation in money for various infractions of formalized law were standardized for the first time in history.[4]

In Medieval times, what we now call economy was not far from the subsistence level. Most exchange occurred within social groups. On top of this, the great conquerors raised venture capital to finance their land captures. The capital investment would be returned to the investor when goods from the newly discovered or captured lands were returned by the conquerors. The endeavors of Marco Polo (1254-1324), Christopher Columbus (1451-1506) and Vasco de Gama (1469-1524) set the foundations for a global economy. In 1513 the first stock exchange was founded in Antwerpen.

The lands captured by Europeans became branches of the European states, the so-called "colonies". The rising nation-states Spain, Portugal, France, Great Britain, and the Netherlands tried to control the trade through custom duties and taxes in order to protect their national economy. Mercantilism was a first approach to intermediate between private wealth and public interest.

The first economist in the true meaning of the word was the Scotsman Adam Smith (1723-1790). He defined the elements of a national economy: products are offered at a natural price generated by the use of competition--supply and demand--and the division of labour. He maintained that the basic motive for free trade is human self interest. In Europe, capitalism started to replace the system of mercantilism and led to economic growth. The period today is called the industrial revolution because the system of production and division of labour enabled the mass production of goods.

Capitalism

Capitalism is an economic and social system in which capital and the non-labor factors of production or the means of production are privately controlled; labor, goods and capital are traded in markets; profits are taken by owners or invested in technologies and industries; and wages are paid to labor.

Capitalism as a system developed incrementally from the 16th century on in Europe, although capitalist-like organizations existed in the ancient world, and early aspects of merchant capitalism flourished during the Late Middle Ages.[5][6] Capitalism gradually spread throughout Europe and other parts of the world. In the 19th and 20th centuries, it provided the main means of industrialization throughout much of the world.[7]

History

The origins of modern markets can be traced back to the Roman Empire[8] and the Islamic Golden Age and Muslim Agricultural Revolution[9][10] where the first market economy and earliest forms of merchant capitalism took root between the 8th–12th centuries.[11]

The economic system employed between the 16th and 18th centuries is commonly described as mercantilism.[19] This period was associated with geographic "discoveries" by merchant overseas traders, especially from England, and the rapid growth in overseas trade. Mercantilism was a system of trade for profit, although commodities were still largely produced by non-capitalist production methods.[7]

The commercial stage of capitalism began with the founding of the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company.[12] During this era, merchants, who had traded under the previous stage of mercantilism, invested capital in the East India Companies and other colonies, seeking a return on investment, setting the stage for capitalism.

During the Industrial Revolution, the industrialist replaced the merchant as a dominant actor in the capitalist system and effected the decline of the traditional handicraft skills of artisans, guilds, and journeymen. Also during this period, the surplus generated by the rise of commercial agriculture encouraged increased mechanization of agriculture. Industrial capitalism marked the development of the factory system of manufacturing, characterized by a complex division of labor between and within the work process and the routinization of work tasks.[19]

In the late 19th century, the control and direction of large areas of industry came into the hands of trusts, financiers and holding companies. This period was dominated by an increasing number of oligopolistic firms earning supernormal profits.[21] Major characteristics of capitalism in this period included the establishment of large industrial monopolies; the ownership and management of industry by financiers divorced from the production process; and the development of a complex system of banking, an equity market, and corporate holdings of capital through stock ownership.[7] Inside these corporations, a division of labor separates shareholders, owners, managers, and actual laborers.[7]

By the last quarter of the 19th century, the emergence of large industrial trusts had provoked legislation in the US to reduce the monopolistic tendencies of the period. Gradually, during this era, the US government played a larger and larger role in passing antitrust laws and regulation of industrial standards for key industries of special public concern. By the end of the 19th century, economic depressions and boom and bust business cycles had become a recurring problem.

In his book The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1904-1905), Max Weber sought to trace how Protestant faith helped form the basis of modern Western capitalism. Protestants emphasized daily work in various occupations as God's calling, and they believed in stewardship of money and property in service to God. This motivated them to work hard, to handle money carefully, and to avoid wasteful behaviors such as gambling and drunkenness. They accumulated wealth through work, self-discipline, saving, and reinvesting. Also, according to Weber, some Protestants believe that prosperity could serve as evidence of being chosen by God for salvation, and this made them work all the harder. Some details of Weber's theory may be mistaken, but there is little doubt that "the Protestant work ethic" was significant for economic development.

How Capitalism Works

The economics of capitalism developed out of the interactions of the following five items:

1. Commodities: There are two types of commodities: capital goods and consumer goods. Capital goods are products not produced for immediate consumption (i.e. land, raw materials, tools machines and factories), but serve as the raw materials for consumer goods (i.e. televisions, cars, computers, houses) to be sold to others.

2. Money: Money is primarily a standardized means of exchange which serves to reduce all goods and commodities to a standard value. It eliminates the cumbersome system of barter by separating the transactions involved in the exchange of products, thus greatly facilitating specialization and trade through encouraging the exchange of commodities.

3. Labour power: Labour includes all mental and physical human resources, including entrepreneurial capacity and management skills, which are needed to transform one type of commodity into another.

4. Means of production: All manufacturing aids to production such as tools, machinery, and buildings.

5. Production: The act of making goods or services through the combination of labour power and means of production.[23][24]

Individuals engage in the economy as consumers, producers, labourers, and investors, providing both money and labour power. For example, as consumers, individuals influence production patterns through their purchase decisions, as producers will change production to produce what consumers want to buy. As labourers, individuals may decide which jobs to prepare for and in which markets to look for work. As investors they decide how much of their income to save and how to invest their savings. These savings, which become investments, provide much of the money that businesses need to grow.

Business firms decide what to produce and where this production should occur. They also purchase capital goods to convert them into consumer goods. Businesses try to influence consumer purchase decisions through marketing as well as the creation of new and improved products. What drives the capitalist economy is the constant search for profits (revenues minus expenses). This need for profits, known as the profit motive, ensures that companies produce the goods and services that consumers desire and are able to buy. In order to be successful, firms must sell a certain quantity of their products at a price high enough to yield a profit. A business may consequently lose money if sales fall too low or costs are incurred that are too high. The profit motive also encourages firms to operate efficiently by using their resources in the most productive manner. By using less materials, labour or capital, a firm can cut its production costs which can lead to increased profits.

Following Adam Smith, Karl Marx distinguished the use value of commodities from their exchange value in the market. Capital, according to Marx, is created with the purchase of commodities for the purpose of creating new commodities with an exchange value higher than the sum of the original purchases. For Marx, the use of labor power had itself become a commodity under capitalism; the exchange value of labor power, as reflected in the wage, is less than the value it produces for the capitalist. This difference in values, he argues, constitutes surplus value, which the capitalists extract and accumulate. The extraction of surplus value from workers is called exploitation. In his book Capital, Marx argues that the capitalist mode of production is distinguished by how the owners of capital extract this surplus from workers: all prior class societies had extracted surplus labor, but capitalism was new in doing so via the sale-value of produced commodities.[25] Marx argues that a core requirement of a capitalist society is that a large portion of the population must not possess sources of self-sustenance that would allow them to be independent, and must instead be compelled, in order to survive, to sell their labor for a living wage.[26][27][28] In conjunction with his criticism of capitalism was Marx's belief that exploited labor would be the driving force behind a revolution to a socialist-style economy.[29] For Marx, this cycle of the extraction of the surplus value by the owners of capital or the bourgeoisie becomes the basis of class struggle. This argument is intertwined with Marx's version of the labor theory of value asserting that labor is the source of all value, and thus of profit. How capitalists generate profit is illustrated in the figure below.

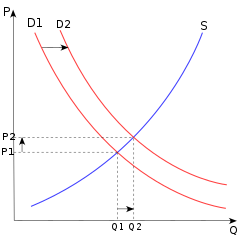

The market is a term used by economists to describe a central exchange through which people are able to buy and sell goods and services.[30] In a capitalist economy, the prices of goods and services are controlled mainly through supply and demand and competition. Supply is the amount of a good or service produced by a firm and available for sale. Demand is the amount that people are willing to buy at a specific price. Prices tend to rise when demand exceeds supply and fall when supply exceeds demand, so that the market is able to coordinate itself through pricing until a new equilibrium price and quantity is reached. Competition arises when many producers are trying to sell the same or similar kinds of products to the same buyers. Competition is important in capitalist economies because it leads to innovation and more reasonable prices as firms that charge lower prices or improve the quality of their product can take buyers away from competitors (i.e., increase market share. Furthermore, without competition, a monopoly or cartel may develop. A monopoly occurs when a firm supplies the total output in the market. When this occurs, the firm can limit output and raise prices because it has no fear of competition. A cartel is a group of firms that act together in a monopolistic manner to control output and raise prices. Many countries have competition laws and anti-trust laws that prohibit monopolies and cartels from forming. In many capitalist nations, public utilities (communications, gas, electricity, etc), are able to operate as a monopoly under government regulation due to high economies of scale.

Income in a capitalist economy depends primarily on what skills are in demand and what skills are currently being supplied. People who have skills that are in scarce supply are worth a lot more in the market and can attract higher incomes. Competition among employers for workers and among workers for jobs, helps determine wage rates. Firms need to pay high enough wages to attract the appropriate workers; however, when jobs are scarce workers may accept lower wages than when jobs are plentiful. Labour unions and the government also influence wages in capitalist nations. Unions act to represent labourers in negotiations with employers over such things as wage rates and acceptable working conditions. Most countries have an established minimum wage and other government agencies work to establish safety standards. Unemployment is a necessary component of a capitalist economy to insure an excessive pool of laborers. Without unemployed individuals in a capitalist economy, capitalists would be unable to exploit their workers because workers could demand to be paid what they are worth. What's more, when people leave the employed workforce and experience a period of unemployment, the longer they stay out of the workforce, the longer it takes to find work and the lower their returning salaries will be when they return to the workforce.[31] Thus, not only do the unemployed help drive down the wages of those who are employed, they also suffer financially when they do return to the paid workforce.

In capitalist nations, the government allows for private property and individuals are allowed to work where they please. The government also generally permits firms to determine what wages they will pay and what prices they will charge for their products. The government also carries out a number of important economic functions. For instance, it issues money, supervises public utilities and enforces private contracts. Laws, such as policy competition, protect against competition and prohibit unfair business practices. Government agencies regulate the standards of service in many industries, such as airlines and broadcasting, as well as financing a wide range of programs. In addition, the government regulates the flow of capital and uses things such as the interest rate to control factors such as inflation and unemployment.

Criticisms of Capitalism

Critics argue that capitalism is associated with the unfair distribution of wealth and power; a tendency toward market monopoly or oligopoly (and government by oligarchy); imperialism, counter-revolutionary wars and various forms of economic and cultural exploitation; repression of workers and trade unionists, and phenomena such as social alienation, economic inequality, unemployment, and economic instability. Critics have argued that there is an inherent tendency towards oligopolistic structures when laissez-faire laws are combined with capitalist private property. Capitalism is regarded by many socialists to be irrational in that production and the direction of the economy are unplanned, creating inconsistencies and internal contradictions and thus should be controlled through public policy.[32]

Environmentalists have argued that capitalism requires continual economic growth, and will inevitably deplete the finite natural resources of the earth, and other broadly utilized resources.

A common response to the criticism that capitalism leads to inequality is the argument that capitalism also leads to economic growth and generally improved standards of living, such as better availability of food, housing, clothing, and health care.[38]

Socialism

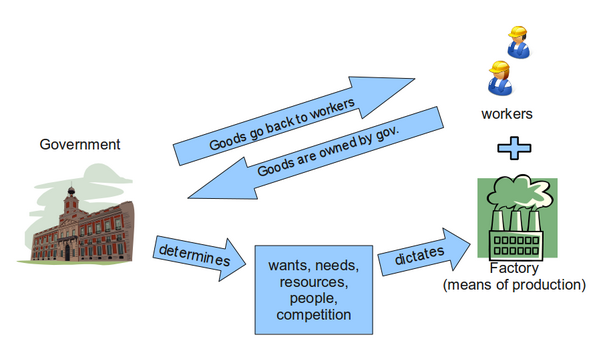

Socialism refers to various theories of economic organization advocating public or direct worker ownership and administration of the means of production and allocation of resources, and a society characterized by equal access to resources for all individuals with a method of compensation based on the amount of labor expended.[41] Most socialists share the view that capitalism unfairly concentrates power and wealth among a small segment of society that controls capital and derives its wealth through exploitation, creates an unequal society, does not provide equal opportunities for everyone to maximise their potentialities[42] and does not utilise technology and resources to their maximum potential nor in the interests of the public.[43]

In one example of socialism, the Soviet Union, state ownership was combined with central planning. In this scenario, the government determined which goods and services were produced, how they were to be produced, the quantities, and the sale prices. Centralized planning is an alternative to allowing the market (supply and demand) to determine prices and production. In the West, neoclassical liberal economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman said that socialist planned economies would fail because planners could not have the business information inherent to a market economy, nor could managers in Soviet-style socialist economies match the motivation of profit. Consequent to Soviet economic stagnation in the 1970s and 1980s, socialists began to accept parts of these critiques.

In western Europe, particularly in the period after World War II, many socialist parties in government implemented what became known as mixed economies. These governments nationalised major and economically vital industries while permitting a free market to continue in the rest. These were most often monopolistic or infrastructural industries like mail, railways, power and other utilities. Typically, this was achieved through compulsory purchase of the industry (i.e. with compensation).

Marxist and non-Marxist social theorists agree that socialism developed in reaction to modern industrial capitalism, but disagree on the nature of their relationship. Émile Durkheim posits that socialism is rooted in the desire to bring the state closer to the realm of individual activity. In socialism, Max Weber saw acceleration of the rationalisation started in capitalism. As a critic of socialism, he warned that placing the economy entirely in the state's bureaucratic control would result in an "iron cage of future bondage".

Social democrats propose selective nationalisation of key national industries in mixed economies, while maintaining private ownership of capital and private business enterprise. Social democrats also promote tax-funded welfare programs and regulation of markets. Many social democrats, particularly in European welfare states, refer to themselves as socialists, introducing a degree of ambiguity to the understanding of what the term means.

Criticisms of Socialism

Criticisms of socialism range from claims that socialist economic and political models are inefficient or incompatible with civil liberties to condemnation of specific socialist states. In the economic calculation debate, classical liberal Friedrich Hayek argued that a socialist command economy could not adequately transmit information about prices and productive quotas due to the lack of a price mechanism, and as a result it could not make rational economic decisions. Ludwig von Mises argued that a socialist economy was not possible at all, because of the impossibility of rational pricing of capital goods in a socialist economy since the state is the only owner of the capital goods. Hayek further argued that the social control over distribution of wealth and private property advocated by socialists cannot be achieved without reduced prosperity for the general populace, and a loss of political and economic freedoms.[71][72]

Socialism's Failure (David Feddes slide)

Capitalism

is the unequal distribution of blessing. Socialism is the equal distribution of

misery. (Winston Churchill)

The

trouble with socialism is that eventually you run out of other people’s money.

(Margaret Thatcher)

Economic Measures

GDPThe Gross Domestic Product or GDP of a country is a measure of the size of its economy. While often useful, it should be noted that GDP only includes economic activity for which money is exchanged. GDP and GDP per capita are widely used indicators of a country's wealth. The map below shows GDP per capita of countries around the world:

Gini Coefficient

The Gini coefficient is a statistical measure of a country's income inequality. A Gini coefficient of zero expresses perfect equality, where all values are the same (for example, where everyone has the same income). A Gini coefficient of one (or 100%) expresses maximal inequality among values (for example where only one person has all the income). Some studies have suggested that greater income inequality lead to poorer health.

Informal Economy

An informal economy is economic activity that is neither taxed nor monitored by a government and is contrasted with the formal economy as described above. The informal economy is thus not included in a government's Gross National Product or GNP. Although the informal economy is often associated with developing countries, all economic systems contain an informal economy in some proportion. Informal economic activity is a dynamic process which includes many aspects of economic and social theory including exchange, regulation, and enforcement. By its nature, it is necessarily difficult to observe, study, define, and measure. The terms "under the table" and "off the books" typically refer to this type of economy. The term black market refers to a specific subset of the informal economy. Examples of informal economic activity include: the sale and distribution of illegal drugs and unreported payments for house cleaning or baby sitting.

Additional Reading

Esping-Andersen, Gosta. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Cambridge: Polity Press. Esping-Andersen, Gosta. 1999. Social Foundations of Postindustrial Economies. Oxford University Press. Chaps. Korpi, Walter and Joachim Palme. 1998. “The Paradox of Redistribution and Strategies of Equality: Welfare State Institutions, Inequality, and Poverty in the Western Countries.” American Sociological Review 63(5):661-687. Orloff, Ann S. 2002. “Explaining US Welfare Reform: Power, Gender, Race and the US Policy Legacy.” Critical Social Policy 22: 96-118 Allen, Michael Patrick and John Campbell. 1994. “State Revenue Extraction from Different Income Groups: Variations in Tax Progressivity in the United States, 1916-1986.” American Sociological Review 59: 169-86. Jacobs, David and Ronald Helms. 2001. “Racial Politics and Redistribution: Isolating the Contingent Influence of Civil Rights, Riots, and Crime on Tax Progressivity.” Social Forces 80: 91-121. Piven, Frances Fox and Richard Cloward. 1993. (2nd Edition). Regulating the Poor: The Functions of Public Welfare. Vintage. Prasad, Monica. 2006. The Politics of Free Markets: The Rise of Neoliberal Economic Policies in Britain, France, Germany, & The United States. University of Chicago Press.

Discussion Questions

- Is the US a purely capitalist country?

- Would you want a capitalist police force?

- What is the difference between socialism and communism? Is there a difference?

- What would you, personally, prefer: an economy closer to capitalism or closer to socialism?

- Can you think of an alternative economic system?

References

- Jump up↑ Herodotus. Histories, I, 94

- Jump up↑ http://rg.ancients.info/lion/article.html Goldsborough, Reid. "World's First Coin"

- Jump up↑ Charles F. Horne, Ph.D. (1915). "The Code of Hammurabi : Introduction". Yale University. Retrieved September 14 2007.

- ↑ Jump up to:a b Sheila C. Dow (2005), "Axioms and Babylonian thought: a reply", Journal of Post Keynesian Economics 27 (3), p. 385-391.

- Jump up↑ Braudel, Fernand. 1982. The Wheels of Commerce, Vol. 2, Civilization & Capitalism 15th-18th Century. University of California Press. Los Angeles.

- Jump up↑ Banaji, Jairus. 2007. Islam, the Mediterranean and the rise of capitalism. Journal of Historical Materialism. 15, 47–74.

- ↑ Jump up to:a b c d Scott, John. 2005. Industrialism: A Dictionary of Sociology Oxford University Press. Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Scott2005" defined multiple times with different content - Jump up↑ Erdkamp, Paul (2005), "The Grain Market in the Roman Empire", (Cambridge University Press)

- Jump up↑ Hasan, M (1987) "History of Islam". Vol 1. Lahore, Pakistan: Islamic Publications Ltd. p. 160.

- Jump up↑ The Cambridge economic history of Europe, p. 437. Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0521087090.

- Jump up↑ Subhi Y. Labib (1969), "Capitalism in Medieval Islam", The Journal of Economic History 29 (1), pp. 79–96.

- ↑ Jump up to:a b c Banaji, Jairus. (2007), "Islam, the Mediterranean and the rise of capitalism", Historical Materialism 15 (1), pp. 47–74, Brill Publishers.

- Jump up↑ Lopez, Robert Sabatino, Irving Woodworth Raymond, Olivia Remie Constable (2001), Medieval Trade in the Mediterranean World: Illustrative Documents, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0231123574.

- Jump up↑ Kuran, Timur (2005), "The Absence of the Corporation in Islamic Law: Origins and Persistence", American Journal of Comparative Law 53, pp. 785–834 [798–9].

- Jump up↑ Labib, Subhi Y. (1969), "Capitalism in Medieval Islam", The Journal of Economic History 29 (1), pp. 79–96 [92–3].

- Jump up↑ Spier, Ray. (2002), "The history of the peer-review process", Trends in Biotechnology 20 (8), p. 357-358 [357].

- Jump up↑ Arjomand, Said Amir. (1999), "The Law, Agency, and Policy in Medieval Islamic Society: Development of the Institutions of Learning from the Tenth to the Fifteenth Century", Comparative Studies in Society and History 41, pp. 263–93. Cambridge University Press.

- Jump up↑ Amin, Samir. (1978), "The Arab Nation: Some Conclusions and Problems", MERIP Reports 68, pp. 3–14 [8, 13].

- ↑ Jump up to:a b Burnham, Peter (2003). Capitalism: The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Oxford University Press.

- Jump up↑ Polanyi, Karl. 1944. The Great Transformation. Beacon Press,Boston.

- Jump up↑ [Economy Professor http://www.economyprofessor.com/economictheories/monopoly-capitalism.php]

- Jump up↑ Engerman, Stanley L. 2001. The Oxford Companion to United States History. Oxford University Press.

- Jump up↑ Ragan, Christopher T.S., and Richard G. Lipsey. Microeconomics. Twelfth Canadian Edition ed. Toronto: Pearson Education Canada, 2008. Print.

- Jump up↑ Robbins, Richard H. Global problems and the culture of capitalism. Boston: Allyn & Bacon, 2007. Print.

- Jump up↑ Capital. v. 3. Chapter 47: Genesis of capitalist ground rent

- Jump up↑ Karl Marx. Chapter Twenty-Five: The General Law of Capitalist Accumulation. Das Kapital.

- Jump up↑ Dobb, Maurice. 1947. Studies in the Development of Capitalism. New York: International Publishers Co., Inc.

- Jump up↑ Harvey, David. 1989. The Condition of Postmodernity.

- Jump up↑ Wheen, Francis Books That Shook the World: Marx's Das Kapital1st ed. London: Atlantic Books, 2006

- Jump up↑ swedberg, richard. 2007. “the market.” Contexts 6:64-66.

- Jump up↑ Arranz, Jose M., Carlos Garcia-Serrano, and Maria A. Davia. 2010. “Worker Turnover and Wages in Europe: The Influence of Unemployment and Inactivity.” The Manchester School 78:678-701.

- Jump up↑ Brander, James A. Government policy toward business. 4th ed. Mississauga, Ontario: John Wiley & Sons Canada, Ltd., 2006. Print.

- Jump up↑ [http://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/imp-hsc/index.htm Lenin, Vladimir. 1916. Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism

- Jump up↑ Horvat, B. The Political Economy of Socialism. Armonk, NY. M.E.Sharpe Inc.

- Jump up↑ Cass. 1999. Towards a Comparative Political Economy of Unfree Labor

- Jump up↑ Lucas, Robert E. Jr. The Industrial Revolution: Past and Future. Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis 2003 Annual Report. http://www.minneapolisfed.org/pubs/region/04-05/essay.cfm

- Jump up↑ DeLong, J. Bradford. Estimating World GDP, One Million B.C. – Present. http://www.j-bradford-delong.net/TCEH/1998_Draft/World_GDP/Estimating_World_GDP.html Accessed: 2008-02-26

- Jump up↑ Nardinelli, Clark. Industrial Revolution and the Standard of Living. http://www.econlib.org/library/Enc/IndustrialRevolutionandtheStandardofLiving.html Accessed: 2008-02-26

- Jump up↑ Prasad, Monica. 2012. The Land of Too Much: American Abundance and the Paradox of Poverty; Harvard University Press

- Jump up↑ Prasad, Monica. 2006. The Politics of Free Markets: The Rise of Neoliberal Economic Policies in Britain, France, Germany, and the United States;University of Chicago Press

- Jump up↑ Newman, Michael. 2005. Socialism: A Very Short Introduction, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-280431-6

- Jump up↑ Socialism, (2009), in Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved October 14, 2009, from Encyclopædia Britannica Online: http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/551569/socialism, "Main" summary: "Socialists complain that capitalism necessarily leads to unfair and exploitative concentrations of wealth and power in the hands of the relative few who emerge victorious from free-market competition—people who then use their wealth and power to reinforce their dominance in society."

- Jump up↑ Marx and Engels Selected Works, Lawrence and Wishart, 1968, p. 40. Capitalist property relations put a "fetter" on the productive forces.

- Jump up↑ John Barkley Rosser and Marina V. Rosser, Comparative Economics in a Transforming World Economy (Cambridge, MA.: MIT Press, 2004).

- Jump up↑ Beckett, Francis, Clem Attlee, (2007) Politico's.

- Jump up↑ Socialist Party of Great Britain. 1985. The Strike Weapon: Lessons of the Miners’ Strike. Socialist Party of Great Britain. London. http://www.worldsocialism.org/spgb/pdf/ms.pdf

- Jump up↑ Hardcastle, Edgar. 1947. The Nationalisation of the Railways Socialist Standard. 43:1 http://www.marxists.org/archive/hardcastle/1947/02/railways.htm

- Jump up↑ http://www.economictheories.org/2008/07/karl-marx-socialism-and-scientific.html

- Jump up↑ Schaff, Kory. 2001. Philosophy and the problems of work: a reader. Rowman & Littlefield. Lanham, MD. ISBN 0-7425-0795-5

- Jump up↑ Walicki, Andrzej. 1995. Marxism and the leap to the kingdom of freedom: the rise and fall of the Communist utopia. Stanford University Press. Stanford, CA. ISBAN 0-8047-2384-2

- Jump up↑ "Market socialism," Dictionary of the Social Sciences. Craig Calhoun, ed. Oxford University Press 2002

- Jump up↑ "Market socialism" The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Politics. Ed. Iain McLean and Alistair McMillan. Oxford University Press, 2003

- Jump up↑ Stiglitz, Joseph. "Whither Socialism?" Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1995

- Jump up↑ http://www.fsmitha.com/h3/h44-ph.html

- Jump up↑ Karl Marx: did he get it all right?, The Times (UK), October 21, 2008, http://www.timesonline.co.uk/tol/news/politics/article4981065.ece

- Jump up↑ Capitalism has proven Karl Marx right again, The Herald (Scotland), 17 Sep 2008, http://www.heraldscotland.com/capitalism-has-proven-karl-marx-right-again-1.889708

- Jump up↑ Gumbell, Peter. Rethinking Marx, Time magazine, 28 January 2009, http://www.time.com/time/specials/packages/article/0,28804,1873191_1873190_1873188,00.html

- Jump up↑ Capitalist crisis - Karl Marx was right Editorial, The Socialist, 17 Sep 2008, www.socialistparty.org.uk/articles/6395

- Jump up↑ Cox, David. Marx is being proved right. The Guardian, 29 January 2007, http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2007/jan/29/marxisbeingprovedright

- Jump up↑ Communist Party of Nepal'

- Jump up↑ [http://www.countryrisk.com/editorials/archives/cat_singapore.html CountryRisk Maintaining Singapore's Miracle

- Jump up↑ Japan's young turn to Communist Party as they decide capitalism has let them down - Daily Telegraph October 18, 2008

- Jump up↑ "Communism on rise in recession-hit Japan", BBC, May 4, 2009

- Jump up↑ Germany’s Left Party woos the SPD'

- Jump up↑ Germany: Left makes big gains in poll https://archive.is/20120803142254/www.greenleft.org.au/2009/813/41841

- Jump up↑ Christofias wins Cyprus presidency'

- Jump up↑ Danish centre-right wins election http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/world/europe/7091941.stm

- Jump up↑ Has France moved to the right? http://www.socialismtoday.org/110/france.html

- Jump up↑ Le Nouveau parti anticapitaliste d'Olivier Besancenot est lancé Agence France-Presse, June 29, 2008

- Jump up↑ Rasmussen Reports http://www.rasmussenreports.com/public_content/politics/general_politics/april_2009/just_53_say_capitalism_better_than_socialism , accessed October 23, 2009.

- Jump up↑ Hayek, Friedrich. 1994. The Road to Serfdom. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-32061-8

- Jump up↑ Hoppe, Hans-Hermann A Theory of Socialism and Capitalism. Kluwer Academic Publishers. page 46 in PDF.