Reading: New Dimensions in Everyday Life

New Dimensions in Everyday Life

City life or country life? The typical farmer rose with the sun, tended the animals, worked the fields, broke bread with the family, and retired when the sun went down. With the exceptions of the Sabbath and holiday observances, life remained constant, changing only with the seasons.

While this bucolic lifestyle was and still is romanticized by many, it simply bore no resemblance to big city existence. The city promised conveniences, nightlife, excitement and variety. Despite its darker side, many were willing to sample cosmopolitan life. The contrast and struggle between rural and urban America raged throughout the last half of the 19th century. Although each side had its proponents, by 1900 one fact was clear. The city was winning.

Cities Change America

URBANIZATION brought greater change to postwar America than any other single factor. As America modernized, pressures to reform education from early childhood through adulthood brought marked improvements. Increased worker productivity and labor demands for a shorter work day enabled many urban residents to engage in newly popular sports and leisure activities unknown in the countryside.

Simply put, such a concentration of people enabled the flourishing of ideas and enterprises, from professional sports to elite clubs. The opportunities were there for the taking for those who had the means. Metropolitan residents became more worldly as they had greater access to the explosion of new forms of printed materials such as more extensive newspapers and a wider variety of periodicals.

City life also redefined gender roles. The average size of the American family dropped from seven children in 1800 to approximately four a century later. Crude birth control methods contributed somewhat to this decline, but large families simply were not as desirable in the city as on the farm. A farm child promised additional agricultural labor, but an urban child was simply an extra mouth to feed.

As women slowly became more educated and independent, traditional Victorian values were challenged. New jobs were available in the city, especially for single women. Demands for NATIONAL REFORM such as prohibition of alcohol, regulation of CHILD LABOR, and the right to vote were brought into public discourse by educated women.

Daily life was changed forever. Although the rural population of America remained an absolute majority until 1920, city life permeated American culture. Critics condemned the slums and vices of urban life, but the cities grew and grew as the American farmer struggled for survival.

Education

Demands for better PUBLIC EDUCATIONwere many. Employers wanted a better educated workforce, at least for the technical jobs. Classical liberals believed that public education was the cornerstone of any democracy. Our system of government could be imperiled if large numbers of uneducated masses voted unwisely.

Teaching America's Youth

Church leaders and modern liberals were concerned for the welfare of children. They believed that a strong education was not only appropriate, but an inalienable right owed to all. Furthermore, critics of child labor practices wanted longer mandatory school years. After all, if a child was in school, he or she would not be in the factory.

In 1870, about half of the nation's children received no formal education whatsoever. Although many states provided for a free public education for children between the ages of 5 and 21, economic realities kept many children working in mines, factories, or on the farm. Only six states had compulsory education laws at this point, and most were for only several weeks per year.

Massachusetts was the leader in tightening laws. By 1890, all children in Massachusetts between the ages of 6 and 10 were required to attend school at least twenty weeks per year. These laws were much simpler to enact than to enforce. TRUANT OFFICERS would be necessary to chase down offenders. Private and religious schools would have to be monitored to ensure quality standards similar to public schools. Despite resistance, acceptance of mandatory elementary education began to spread. By the turn of the century such laws were universal throughout the North and West, with the South lagging behind.

Under the laws of JIM CROW, the public schools in operation in the South were entirely SEGREGATED by race in 1900. Mississippi became the last state to require elementary education in 1918.

Other reforms began to sweep the nation. Influenced by German immigrants,KINDERGARTENS sprouted in urban areas, beginning with St. Louis in 1873. Demands for better trained teachers led to an increase in "normal" schools, colleges that specialized in preparation to teach. By 1900, one in five public school teachers had a degree.

More and more high schools were built in the last three decades of the 19th century. During that period the number of public high schools increased from 160 to 6,000, and the nation's ILLITERACY rate was cut nearly in half. However, only 4% of American children between the ages of 14 and 17 were actually enrolled.

Higher Education for All

Higher education was changing as well. In general, the number of colleges increased owing to the creation of public land-grant colleges by the states and private universities sponsored by philanthropists, such as Stanford and Vanderbilt.

Opportunities for women to attend college were also on the rise. MT. HOLYOKE,SMITH, VASSAR, WELLESLEY, and BRYN MAWR Colleges provided a liberal arts education equivalent to their males-only counterparts. By 1910, 40% of the nation's college students were female, despite the fact that many professions were still closed to women.

Although nearly 47% of the nation's colleges accepted women, African American attendance at white schools was virtually nonexistent. BLACK COLLEGES such as HOWARD, FISK, and ATLANTA UNIVERSITY rose to meet this need.

Sports and Leisure

A sports craze was sweeping the nation. Work weeks were still long, averaging about sixty hours per week in 1890. But the average worker notched 66 hours in 1860, giving the typical American six extra hours of free time each week. Three more decades would see an additional 10 hours of average working time turn into free time.

What did Americans do with all this time? Participation in sports, leisure, and amusement activities multiplied.

Take Me out to the Ball Game

BASEBALL was quickly becoming the national pastime. It had graduated from a gentleman's game to a form of mass entertainment. As cities and towns dedicated more and more public land for recreational purposes, baseball became more and more popular. Those who did not enjoy playing were given the opportunity to watch.

Moses Fleetwood Walker was the first African-American to play on a major league baseball team (the Toledo Blue Stockings).

The NATIONAL LEAGUE was formed in 1876 and Americans were able to watch touring professionals play the game. As a color barrier had been quickly established, not all athletes were given an opportunity. The National League and its rival, the AMERICAN LEAGUE, played for the first WORLD SERIES CHAMPIONSHIP in 1903. The baseball craze led to the financing of large grandstand arenas such as FENWAY PARK in Boston, SHIBE PARK in Philadelphia, and WRIGLEY FIELD in Chicago.

Other spectator sports were also popular.FOOTBALL had a large following, particularly on the college level. Universities were accused of hiring ringers (professionals) to help them win games. The rules were fairly lax, and many injuries resulted. In 1905, eighteen players were killed by injuries related to football.

BOXING became more respectable with a new innovation — gloves.BASKETBALL was invented in 1891 in Springfield, Massachusetts by JAMES NAISMITH, a YMCA instructor. Designed as an indoor sport, basketball enabled athletic competition during the winter months. Croquet and tennis provided the only opportunity in sport for coed play.

Vaudville

Other forms of mass entertainment also flourished. The most popular form of urban performance was the VAUDEVILLE SHOW. An evening at vaudeville might last two or three hours, as audiences watched nine or ten different acts, ranging from singing and dancing to stand-up comedy and acrobatics. The first vaudeville theater was opened in 1881 by TONY PASTOR in Manhattan. Eventually, New York had ten vaudeville theaters, and every major city could boast at least one.

For the children, PHINEAS T. BARNUM AND JAMES A. BAILEY presented "THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH," a three-ring circus complete with exotic animals, trapeze artists, and big tent.

Age of the Bicycle

The velocipede became popular in the later half of the 19th century. While the larger front wheel allowed for greater speed, the potential fall was quite dangerous.

On an individual level, the turn of the century was also the age of the bicycle. In 1885, theVELOCIPEDE, a "bicycle" with one huge wheel followed by a smaller one, became instantly obsolete when the safer, modern bicycle with two wheels of equal size made its debut.

Many became addicted to this new form of exercise. Men and women took romantic rides through parks, and courtship took a step closer to independence from parental involvement.

The bicycle even had an impact on women's fashion. No one could ride around on a bicycle with a big Victorian hoop dress, so designers accommodated the new trend by producing a freer, less constrictive style.

Women in the Gilded Age

The idea was to create a maternal commonwealth. Upper-middle-class women of the late 19th century were not content with the cult of domesticity of the early 1800s. Many had become college educated and yearned to put their knowledge and skills to work for the public good.

MATERNAL COMMONWEALTHmeant just that. The values of WOMEN'S SPHERE— caretaking, piety, purity — would be taken out of the home and placed in the public life. The result was a broad reform movement that transformed America.

Just Say No to Alcohol

Many educated women of the age felt that many of society's greatest disorders could be traced to ALCOHOL. According to their view, alcohol led to increased domestic violence and neglect. It decreased the income families could spend on necessities and promoted prostitution and adultery. In short,PROHIBITION of alcohol might diminish some of these maladies.

Frances Willard was the president of the WOMAN'S CHRISTIAN TEMPERANCE UNION, the nation's foremost prohibition organization. Although national prohibition was not enacted until 1919, the WCTU was successful at pressuring state and local governments to pass dry laws. Willard advocated a "DO EVERYTHING" policy, which meant that chapters of the WCTU also served as soup kitchens or medical clinics.

The WCTU worked within the system, but there were radical TEMPERANCEadvocates who did not. CARRY NATION preferred the direct approach of taking an ax into saloons and chopping the bars to pieces.

Homes for the Destitute

Another way women promoted the values of women's sphere into the public arena was through the SETTLEMENT HOUSE MOVEMENT. A SETTLEMENT HOUSE was a home where destitute immigrants could go when they had nowhere else to turn. Settlement houses provided family-style cooking, lessons in English, and tips on how to adapt to American culture.

The first settlement house began in 1889 in Chicago and was called HULL HOUSE. Its organizer, JANE ADDAMS, intended Hull House to serve as a prototype for other settlement houses. By 1900 there were nearly 100 settlement houses in the nation's cities. Jane Addams was considered the founder of a new profession — social work.

Different Backgrounds, Different Lives

Most of the advocates of maternal commonwealth were white, upper-middle-class women. Many of these women had received a college education and felt obliged to put it to use. About half of the women in this demographic group never married, choosing instead independence. Other college educated women were content to join literary clubs to keep academic pursuits alive.

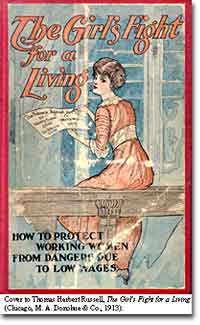

Women and labor

For women who did not attend college, life was much different. Many single, middle-class women took jobs in the new cities. Clerical jobs opened as typewriters became indispensable to the modern corporation. The telephone service required switchboard operators and the new department store required sales positions. Many of these women found themselves feeling marvelously independent, despite the lower wages they were paid in comparison with their male counterparts.

For others, life was less glamorous. Wives of immigrants often took extra tenants called BOARDERS into their already crowded tenement homes. By providing food and laundry service at a fee, they generated necessary extra income for the families. Many did domestic work for the middle class to supplement income.

In the South, the lives of wealthy women changed from managing a home on a slave plantation to one with hired work. Women who found themselves with new freedom from slavery still suffered great difficulties. SHARECROPPING was a male and female task. Women in these conditions found themselves doing double duty by working the fields by day and the house by night.

Victorian Values in a New Age

Victorian values dominated American social life for much of the 19th century. The notion of separate spheres of life for men and women was commonplace. The male sphere included wage work and politics, while the female sphere involved childrearing and domestic work.

Industrialization and urbanization brought new challenges to Victorian values. Men grew weary of toiling tireless hours and yearned for the blossoming leisure opportunities of the age. Women were becoming more educated, but upon graduation found themselves shut out of many professions. Immigrants had never been socialized in the Victorian mindset. As the century drew to a close, a revolt was indeed brewing.

Victoria Battles the Victorians

At the vanguard of revolt were the young, single, middle-class women who worked in the cities. Attitudes toward sex were loosening in private, yet few were brave enough to discuss the changes publicly.

One exception was VICTORIA WOODHULL. In 1871, she declared the right to love the person of her choice as inalienable. Indeed, she professed the right to free love. She and her sister, TENNESSEE CLAFLIN, published their beliefs in the periodical WOODHULL AND CLAFLIN'S WEEKLY.

A devout feminist, Woodhull protested the male hold on politics by running for President in 1872. She became the first female American to do so in a time when women did not even enjoy the right to vote.

The Comstock Law

As energetic as the rebellion may have been, the reaction was equally as forceful. Criticizing the evils of modern urban life — prostitution, gambling, promiscuity, and alcohol — Victorians fought to maintain the values they held dear.

ANTHONY COMSTOCK lobbied Congress to pass the notorious COMSTOCK LAWbanning all mailings of materials of a sexual nature. As a special agent for theUNITED STATES POSTAL SERVICE, Comstock confiscated thousands of books and pictures he deemed objectionable. Over 3,000 arrests were made for violations of the Comstock Law.

However valiantly Victorians fought to maintain their view of morality, they could not stop the changes. A greater acceptance of sexual expression naturally followed — especially in the new American city. For example, regions such as the BOWERY in New York were known by city dwellers as areas where homosexuals found community.

America was evolving, and no one could bottle up that change. The public struggle between Victoria Woodhull and Anthony Comstock merely illustrated the underlying tensions between old and new values.

The Print Revolution

Even the news was a business. As Americans streamed into cities from small towns and overseas, JOURNALISTS realized the economic potential. If half of Boston's citizens would buy a newspaper three times a week, a publisher could become a millionaire.

The LINOTYPE MACHINE, invented in 1883, allowed for much faster printing of many more papers. The market was there. The technology was there. All that was necessary was a group of entrepreneurs bold enough to seize the opportunity. The result was an American revolution in print.

Birth of the Modern Paper

Anybody with a modest sum to invest could buy a printing press and make newspapers. The trick was getting people to buy them.

The modern American NEWSPAPER took its familiar form during the Gilded Age. To capitalize on those who valued Sunday leisure time, the Sunday newspaper was expanded and divided into supplements. The subscription of women was courted for the first time by including fashion and beauty tips. For Americans who followed the emerging professional sports scene, a sports page was added.

"DOROTHEA DIX," actually ELIZABETH GILMER, became the nation's first advice columnist for the NEW ORLEANS PICAYUNE in 1896. To appeal to those completely disinterested in politics and world events, CHARLES DANA of the<i>NEW YORK SUN INVENTED THE HUMAN-INTEREST STORY. THESE ARTICLES OFTEN RETOLD A HEART-WARMING EVERYDAY EVENT LIKE IT WAS NATIONAL NEWS.

Twisting the Truth

The competition was fierce, especially in New York. The two titans of American publishing were JOSEPH PULITZER of the NEW YORK WORLD andWILLIAM RANDOLPH HEARST of the NEW YORK JOURNAL. These men stopped at nothing to increase their readership. If a news story was too boring, why not twist the facts to make it more interesting? If the truth was too bland, why not spice it up with some innocent fiction? If all else failed, the printer could always increase the size of the headlines to make a story seem more important.

This kind of SENSATIONALISM was denounced by veteran members of the press corps. Labeled YELLOW JOURNALISM by its critics, this practice was prevalent in late-19th century news. At its most harmless, it bent reality to add a little extra excitement to everyday life. At its most dangerous, it fired up public opinion to start a war with Spain.

Nevertheless, as a business strategy, it worked. Pulitzer increased the daily circulation of the Journal from 20,000 to 100,000 in one year. By 1900, it had increased to over a million.

The print revolution affected books and magazines as well. The total number of books in print increased fourfold from 1880 to 1917. MAGAZINES such as the SATURDAY EVENING POST and LADIES' HOME JOURNAL reached a broader audience than any previous magazine. America was becoming more populous, more literate, and, as a result of the print revolution, better informed.