Addiction and Its Costs

William S. Cartwright and James M. Kaple

There is renewed interest in the role of health services research in assisting the Nation to improve the delivery of basic drug abuse treatment. The first National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) technical review to focus on the drug services research agenda was convened May 21-22, 1990. The purpose of the technical review was to identify and plan services research dealing with social and economic costs, cost-effectiveness, and financing of drug treatment, prevention, referral, and followup care in health and community settings. The Financing and Services Research Branch (FSRB), Division of Applied Research, NIDA, sponsored this technical review to examine research to develop new methods of analysis and to improve current methods in these areas,

The scientific environment in drug abuse services research is one of active and intense interest in which scientific and programmatic policies are rapidly evolving after a period of neglect. In June 1990, the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) issued a White Paper titled Understanding Drug Treatment (Office of National Drug Control Policy 1990 a). In September 1990, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) published its report, Treating Drug Problems (Institute of Medicine 1990a), and a previous IOM report, Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems (Institute of Medicine 1990b), also was published earlier that year. The ONDCP has published two reports, both titled National Drug Control Strategy (Office of National Drug Control Policy 1989, 1990b), and each discusses national policy and research needs and emphasizes services research as an important and integral part of a well-rounded research strategy. The FSRB is charged to nurture the development of basic and applied research in the drug abuse services field.

This technical review used three main themes to organize the issues. First, the review focused on the development of the latest cost estimates associated with drug abuse and considered new approaches to improve the methodology.

Second, issues surrounding the state of cost-effectiveness research of alternative drug treatments were dealt with in four chapters. Third, a review of drug treatment financing from the public and private perspectives examined how funding the delivery of drug treatment and other appropriate services was undertaken. Finally, suggested services research opportunities and data collection needs were examined, building on presentations made throughout the technical review.

Services research investments over the next few years will lead to an improved understanding of the relative effectiveness of organizational, structural, and financial approaches to the Nation’s drug treatment system and the clients it serves. Services research now in place and planned for the future will enhance the knowledge base necessary to inform future policy decisions affecting financing and delivery of drug treatment in the public and private sectors. This technical review contributes to the research process by providing guidance in the assessment of economic costs, cost-effectiveness, and financing issues.

ECONOMIC COSTS OF DRUG ABUSE

Establishing the economic costs of drug abuse presents an interesting challenge to those who develop such estimates and those who would use such estimates for policy purposes. The first chapter, by Rice and coworkers, summarizes the most recent findings on drug abuse economic costs from an FSRB-sponsored study (Rice et al. 1990) that included mental health and alcohol costs. Sindelar and Harwood offer cautionary notes to researchers and policymakers concerning the interpretation of the findings.

Rice and colleagues present a careful analysis of the burden of drug abuse on society. The study uses the human capital approach rather than the willingness-to-pay approach. The study also uses a prevalence approach to estimate a 1985 base period of costs rather than an incidence approach that would attempt to estimate lifetime cost over the sum of affected individuals.

The reader should remember that estimates were generated on data acquired before the crack/cocaine epidemic in the late 1980s and therefore do not capture the additional costs of this new drug usage. Overall, the computations result in a 1985 estimated cost to the Nation of $44 billion, which is updated by inflation only to an 1988 estimate of $58.3 billion. In 1988, $325 billion represented crime-related costs-a large burden to the economy and to those who do not use drugs. Such high crime-related costs distinguish drug abuse costs from those related to alcohol and mental health costs.

This cost-of-illness study contributes, among other things, two technical innovations. First, in estimating productivity losses (income losses) by age and sex, the authors develop a model that takes into account the timing and duration of the drug abuse disorder on current income. To do this, the National Institute of Mental Health Epidemiology Catchment Area data are used along with the available information on time of onset of last drug abuse symptom relative to the time of the interview. Second, new variables for alcohol and drug abuse and mental illness are used as explanatory variables in the income loss equations. A major finding was that the income loss was lower for alcohol and drug abuse than was found in an earlier study conducted by the Research Triangle Institute (Harwood et al. 1984). The new study had the advantage of newer and more complete databases and new statistical models and methods.

The striking thing about these cost estimates is how large the burden is and how much of it falls on society rather than on the individual drug user. The crime portion of this estimate accounts for nearly 74 percent of the total cost.

For policymakers, this crime factor creates a unique situation for financing and reimbursement policy because there are such large external costs on other members of society. One effect of these external costs is a willingness to pay a subsidy for treatment to reduce these costs. The subsidy is present already in the State block grant for alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health (ADM) services, but at what level the subsidy should be set is a question of intense policy interest.

Although such cost-of-illness studies indicate a large burden on society, Sindelar cautions that this is not sufficient information for decisionmaking about the allocation of scarce resources. Additional information must be collected on the marginal effectiveness of policies and programs if decisionmaking is going to move toward an optimum. Second, she recommends focusing studies on individuals with defined constellations of ADM comorbidities rather than artificially parceling diseases into distinct categories when dealing with polysubstance abuse. Finally, Sindelar recommends that attention be paid to certain hidden costs such as the deadweight loss attributable to government taxation to finance public problems.

Harwood suggests additional caveats to the interpretation of cost-of-illness studies. He notes that such studies provide a metric to summarize the burden of disparate diseases, but it is a metric that is limited in calculating other aspects of drug abuse problems such as pain and suffering. He reminds us that, from 1980, cost-of-illness studies have undergone dramatic improvement in methodology. As a result, estimates of the impact of drug abuse on persons in the work force have fundamentally increased over previous estimates.

Finally, Harwood points out that economic concerns of efficiency and equity are primary in the development of a national drug control strategy.

The editors wish to point out the significance of research findings related to the large costs in productivity losses for individuals in the workplace. Such findings underlay the basis for economic arguments of the benefits of workplace drug policies related to testing and treatment. Of course, there will be a need for additional estimates of such effects, although such measurements must be conducted In an environment of heightened consciousness of workplace drug problems. This heightened consciousness potentially biases the best efforts of researchers to control for all Intervening variables. For example, increased levels of general information affected the measured impact of health interventions for reducing heart disease because controls generally were subject to better knowledge concerning changes in healthy behavior. The overall result Is an increased difficulty in detecting a measured difference between the controls and the treatment groups and, hence, a bias to not finding a treatment effect in the workplace.

COST-EFFECTIVENESS

Apsler’s review of the cost-effectiveness literature is a critical assessment of accomplishments to date. For his purpose, the important question is, Are today’s drug treatment programs cost-effective? Apsler develops a three-part argument about the results in the literature. First, there is evidence that some “typical” drug programs are of “questionable” cost-effectiveness. Moreover, there is also evidence that some treatment strategies are “cost-ineffective.”

Finally, there is evidence that certain treatments have a positive cost-effectiveness. Underlying these various estimates is what Apsler suggests is a lack of rigor in research design and implementation. To redress this, he recommends a renewed commitment to undertaking cost-effectiveness studies and to using better research methods.

Hser and Anglin have comprehensively reviewed the effectiveness of drug treatment in a paper published elsewhere (Anglin and Hser 1990). In the chapter for this monograph, they point out new directions for research into cost-effectiveness studies of drug treatment. They start with the definitional and conceptual framework for cost-effectiveness studies and then focus on the dynamic aspects of the treatment system and the client’s career in drug addiction and treatment. Hser and Anglin discuss the use of time-series analysis and its potential for studying the addiction career and for policy analysis. They also discuss survival analysis, Markov and Semi-Markov Modeling, and system dynamics approaches. Within such a methodological focus, they argue that in the framework of these models interventions can be examined to provide policy analysis of alternatives.

Hubbard and French maintain that, on balance, treatment is “an effective and cost-effective strategy.” They recommend that attention be shifted from a defensive posture regarding treatment outcome findings to a more offensive one so that the maximum return on each dollar invested in treatment can be achieved. This theme is strongly recommended throughout the first section on social and economic costs. Hubbard and French’s chapter lays out new perspectives on research to study treatment careers, components of treatment, and the effects of client impairment (assessed at treatment entry). Hubbard and French take a reductionist approach to disaggregating the “black box” of treatment and the client types in the system. They argue that only through this approach can a better understanding of what is cost-effective be developed.

Lampinen examines cost-effectiveness issues in the prevention of acquired lmmunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). He reviews epidemiologic and public health Issues in evaluating cost-effectiveness of drug treatment as an AIDS prevention strategy. The problem Lampinen perceives is that Federal AIDS

prevention dollars are distributed to areas with the highest cumulative incidence rates of diagnosed AIDS cases. This is problematic because AIDS among intravenous (IV) drug users is underweighted in resource discussions and allocations and because the latency period for AIDS is so long. In assessing alternative prevention strategies for IV drug users, he notes that the drug treatment approach may be limited by the lack of treatment slots and the costs associated with treatment. Outreach initiatives to conduct AIDS education and prevention still remain the most logical alternative given the current size of the drug treatment system. Finally, consideration must be given to epidemiologic information on rates of infectivity in weighting prevention strategies so that resource allocations will be more effective.

FINANCING

Gerstein lays out fundamental questions to guide policy research and development. In particular, policy research must focus on public support for financing drug treatment. He posits three principles on which such public policy should focus: (1) reduce external social costs, (2) increase access to care, and (3) stimulate effective treatment. In developing his thesis, Gerstein explores several topics in a wide-ranging discussion that goes beyond considerations of financing. In particular, he discusses the role of cost-of-illness studies, cost-effectiveness and efficiency in treatment, and financing. In financing issues, a problem unique to drug abuse clients is the moral conception about those needing treatment. These moral conceptions play a role in determining the willingness of others to pay for drug treatment and rehabilitation either through the public system or through private, risk-pooling arrangements of private health insurance. Gerstein advocates further research into Medicaid financing of drug treatment, utilization management, incentive effects of regulatory controls, and data requirements.

Duggar notes that in spite of the lack of comprehensive data there are indications that third-party reimbursement for drug treatment has expanded to a greater number of health insurance plans. There has been an expansion in drug treatment coverage as measured in some national surveys, but details on various reimbursement characteristics are not available. Limitations on drug treatment benefits seem more restrictive than what is customary for other health care benefits, but there has been expansion to provide drug treatment and rehabilitation in what are called “other approved facilities,” which include residential treatment facilities and freestanding drug abuse clinics as opposed to costly inpatient care.

Duggar sees great possibilities in Medicaid program expansion where States institute Medicaid coverage for drug treatment. Where this occurs, State licensure activity for Medicaid reimbursement eligibility seems to stimulate private payers’ interest in recognizing legitimate drug treatment programs and in reimbursing for treatment. However, most Medicaid programs exclude reimbursement for residential treatment facilities because there is no Federal funding designated for this activity.

Duggar reports on some preliminary data concerning Pennsylvania’s establishment of a “Health Insuring Organization” (HIO) to enroll a subset of Philadelphia Medicaid clients. The HIO contracted with primary care physicians on a capitated basis to have them serve as gatekeepers to medical care.

Preliminary results indicate some reductions for inpatient hospital costs, but none for drug treatment costs because of the lack of HIO control over outpatient drug treatment episodes. He recommends that such Medicaid demonstrations are important natural experiments for studies of reimbursement for drug treatment.

Pauly examines the current state of financing of treatment for drug abuse and important economic factors that determine adequacy and future policy. He highlights the dual and virtually separate drug treatment provided in the public and private sectors. A fundamental problem facing both sectors is the skepticism of payers that treatment works with any certainty. Thus, third-party payers such as insurance companies, employers, and governments have the difficult problem of determining whether treatment dollars are well spent. Pauly further Indicates that, if there is a rational expectation of effective treatment, then why would treatment be denied? He also asks, Why do the public and private programs differ so greatly?

Pauly develops a series of research questions in logical sequence about public and private financing of drug abuse treatment, with a special section on employment-related insurance coverage. Under public and private financing, drug treatment has a role of providing effective health investments for communities or individuals. Along with such investments, consideration must be given to the distribution of costs across various groups in society. In employment-related insurance coverage, there are several issues, with State mandates for minimal levels of drug abuse treatment coverage having several effects that need to be studied and verified.

McGuire and Shatkin focus on the difficulties of estimating the cost of health insurance for drug treatment. The cost of drug treatment has been perceived as rising rapidly and requiring special attention to manage the cost of insurance.

State and Federal laws attempt to meet social goals by imposing mandates and minimal requirements on the benefits and insurance contracts that may be written in a State, which in turn increases costs to others elsewhere in the economy. Estimates of these costs are a critical component in evaluating the tradeoffs in achieving social goals. The authors critique two studies that examine the impact of providing drug treatment on health insurance premiums and the impact of State mandates to provide drug treatment benefits. McGuire and Shatkin call for studies that can exploit large data sets of insurance claims to examine the response to different reimbursement policies and for studies that focus on determinants of health insurance coverage for drug treatment.

Cartwright and Woodward survey the use of health insurance questions in national surveys to determine appropriate methods for estimation of insurance coverage, substance abuse benefits, and access to care and propose a set of questions to be added to the National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (NHSDA) or other small area surveys. The chapter examines the Current Population Survey (CPS), National Medical Expenditure Survey, and the National Health Interview Survey. In asking questions about illicit use of drugs, it must be remembered that confidentiality and anonymity requirements are important factors in the survey design of the NHSDA. Obtaining household information is difficult because the most knowledgeable person about the household situation may not be questioned because persons within the household are randomly selected. There are also many adolescents who may have limited knowledge about their health insurance coverage. In the face of these problems, it is necessary to use more than one survey to derive a picture concerning health insurance coverage and drug coverage. The authors recommend a strategy using CPS health insurance questions to link data with the NHSDA. In this way, the CPS may be used to provide fundamental data on the Nation’s population and household characteristics that may inform the study of access to and adequacy of drug treatment.

This technical review was a first step for the FSRB toward defining a national research agenda for drug abuse services research. This monograph presents several exciting research opportunities for multidisciplinary research teams to undertake. The technical review examined the methodology of cost-of-illness estimates and reviewed cost-effectiveness and benefit-cost studies, two areas that must be closely linked in the development of the research agenda.

However, financing also was included because of its potential role in providing an important source of information on both costs and benefits. Furthermore, financing issues are sources of research questions on efficiency and equity in the drug treatment system. In drug services research, all the complications of understanding the various roles of the public and private sector are conjoined in questions of financing of the treatment system. The continued development of the services research agenda represents a challenge for the research community as theoretical work is combined with applied, empirical research to achieve the goal of improved public health in the United States.

REFERENCES

Anglin, M.D., and Hser, Y. Treatment of drug abuse. In: Tonry, M., and Wison, J.Q., eds. Crime and Justice: An Annual Review of Research. Vol. 13. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1990.

Harwood, H.J.; Napolitano, D.M.; Kristiansen, P.; and Collins, J.J. Economic Costs to Society of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Mental Illness: 1980.

Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute, 1984.

Institute of Medicine. Broadening the Base of Treatment for Alcohol Problems. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1990b.

Institute of Medicine. Treating Drug Problems. Vol. 1. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1990a.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. National Drug Control Strategy. Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1989.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. National Drug Control Strategy. Washington DC: Supt. of Docs., US. Govt. Print. Off., January 1990b.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. Understanding Drug Treatment Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off., June 1990a.

Rice, D.P.; Kelman, S.; Miller, L.S.; and Dunmeyer, S. The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Mental Illness: 1985. Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., US. Govt. Print. Off., 1990.

William S. Cartwright, Ph.D.

Health Policy Analyst

James M. Kaple, Ph.D.

Associate Director for Services Research

Financing and Services Research Branch

National Institute on Drug Abuse

Room 9A-42

5600 Fishers Lane

Rockville, MD 20857

Dorothy P. Rice, Sander Kelman, and Leonard S. Miller

INTRODUCTION

Drug abuse and drug addiction are costly to the Nation in medical resources used for care, treatment, and rehabilitation; in reduced or lost productivity; in crime enforcement; and in pain and suffering of drug abusers and their families and friends. Although the overall use of drugs has decreased in recent years, drug addiction continues to be widespread and its consequences are more serious (Committee on Ways and Means 1990). The 1988 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse (National Institute on Drug Abuse 1990) estimates that almost 28 million Americans over the age of 12, about one in every seven persons, had used illicit drugs one or more times in the past year. Of these, marijuana (including hashish) was the most commonly used illicit drug, with over 21 million users in the past year, and heroin with about 600,000 users in the past year. The 1988 survey also showed that over 1 million persons used crack in the past year and that nearly 2.5 million persons had used the drug at least once in their lifetime. Crack cocaine, the most addictive drug that scientists have ever confronted, coupled with the emergence of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) among intravenous (IV) drug users, are major public health problems in the United States, flooding hospitals, emergency rooms, drug treatment centers, child welfare systems, and ultimately the Nation’s morgues.

Drug abuse imposes a substantial burden on individuals as well as society as a whole. Although it is difficult to quantify all aspects of the burden that drug abuse imposes on society, it is important to translate this burden into economic terms to facilitate decisionmaking. With the continued rise in health care expenditures and the growing pressures for cost-containment, limited financial resources may limit the health care Americans need. Priorities should allow for the greatest improvement in welfare or well-being per dollar spent. To determine the expenditures on prevention, education, treatment, control, interdiction, and research on drug abuse, it is necessary to understand the burden it places on society as well as the cost and effectiveness of alternative interventions.

The research presented in this chapter developed estimates of the economic burden of drug abuse in 1985. It is part of a larger study, The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Mental Illness: 1985 (Rice et al. 1990), conducted for the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration. This chapter summarizes the methods and sources of data used in estimating the direct and indirect costs of drug abuse and presents the results for 1985 and 1988. The same methodology applies to the costs of alcohol abuse and mental illness that are part of the larger study.

METHODOLOGY

Cost-of-illness studies are typically divided into two major categories: core costs and related costs. Core costs are those resulting directly from the illness, whereas other related costs are the costs of secondary, nonhealth effects of Illness. Within each category, there are direct and indirect costs. Direct costs are those for which payments are actually made, and indirect costs are those for which resources are lost. Indirect costs consist of morbidity and mortality costs. Morbidity costs are the value of lost productivity by persons unable to perform their usual activities or to perform them at a level of full effectiveness due to the illness. Mortality costs are the value of lost productivity due to premature death resulting from illness; lost productivity is calculated as the present discounted value of future market earnings plus an imputed value for housekeeping services.

Human Capital and Willingness-To-Pay Approaches This study uses the human capital approach, whereby an individual is seen as producing a stream of output over time that is valued at market earnings or the imputed value of housekeeping services. It assumes a social perspective and has the important advantage of using data that are reliable and readily available. It is useful for answering questions regarding the economic burden of disease for a specific duration (e.g., drug abuse in 1985) or for cost-benefit analysis (e.g., determining the cost savings of a specific procedure or intervention program that reduces illness and/or improves survival rates). The human capital approach also has limitations. Because the value of human life is based on market earnings, it yields very low values for children and the retired elderly. Many drug abusers fall into these categories, especially young persons. This approach may undervalue or overvalue life if labor market imperfections exist and wages do not reflect true abilities. Finally, certain dimensions of illness and death such as pain and suffering are ignored.

A conceptually different approach, willingness to pay, captures other aspects of the value of life. This method values human life according to what indlviduals would be willing to pay for a change that reduces the probability of illness or death (Schelling 1966; Acton 1975). Objections to the willingness-to-pay method are that it is difficult to implement in practice, that the value of individual lives depends on income distribution (with the rich able to pay more than the poor), and that people have great difficulty in placing a value on small reductions In the probability of death (Hodgson and Meiners 1962). However, the methodology has been refined considerably in recent years (Rice et al. 1989).

Prevalence and lncidence Approaches

Two approaches can be used to estimate the cost of illness by the human capital method. Prevalence-based cost provides an estimate of the direct and indirect economic burden incurred in a period (the base period) as a result of the prevalence of illness during this same base period, most often a year.

Included is the cost of base-year manifestations of illness or associated disability with onset in or at any time before the base year. Prevalence-based cost measures the value of resources used or lost during a specified period regardless of the onset of the illness or injury.

Incidence-based cost represents the lifetime cost resulting from the illness.

Incidence cost refers to the total lifetime cost of all cases with the onset of disease In the base year. Incidence cost is difficult to estimate because it requires knowledge of the likely course of an illness and its duration, including survival rates since onset; the amount and cost of medical care to be used and its cost during the duration of the illness; and the impact of the illness on lifetime employment, housekeeping, and earnings (Hodgson 1983; Scitovsky 1982).

Most cost-of-illness studies employ the prevalence-based approach, as does the one employed in the current study on the economic costs of drug abuse.

Definition of Drug Abuse

Drug abuse is defined as any of the diagnoses listed in the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), as shown in table 1. Included are drug psychoses; drug dependence; nondependent abuse of drugs; poisoning by drugs, including opiates and related narcotics, sedatives, and hypnotics; psychotropic agents, central nervous system (CNS) depressants and stimulants; and heroin, methadone, opiates, and related narcotics causing adverse effects In therapeutic use.

These ICD-9-CM diagnoses are used for estimating the direct drug abuse treatment costs of hospital and ambulatory care from the National Hospital Discharge Survey (NHDS) and the National Ambulatory Care Survey. They also are used for estimating mortality costs based on the number of deaths from these diagnoses reported in the National Mortality Detail File.

| Diagnosis | ICD-9-CMa Code |

|---|---|

| Nondependent abuse of drugs | 305 |

| Polyneuropathy due to drugs | 357.6 |

| Narcotics affecting fetus or newborn via placenta or breast | 760.72 |

| Hallucinogenic agents affecting fetus or newborn via placenta or breast | 760.73 |

| Drug withdrawal syndrome in newborn | 779.5 |

| Poisoning by opiates and related narcotics | 965.0 |

| Poisoning by sedatives and hypnotics | 967 |

| Poisoning by CNS muscle-tone depressants | 968.0 |

| Poisoning by psychotropic agents | 969 |

| Poisoning by CNS stimulants | 970 |

| Heroin causing adverse effects In therapeutic use | E935.0 |

| Methadone causing adverse effects in therapeutic use | E935.1 |

| Other opiates and related narcotics causing adverse effects in therapeutic use | E935.2 |

| Sedatives and hypnotics causing adverse effects in therapeutic use | E937 |

| Other CNS depressants and anesthetics causing adverse effects in therapeutic use | E938 |

| Psychotropic agents causing adverse effects in therapeutic use | E939 |

| CNS stimulants causing adverse effects in therapeutic use | E940 |

aInternational Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification

For estimates of morbidity costs, the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Surveys are used, which classify disorders according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders III, Revised. The ECA data provide diagnostic information on drug abuse and dependence for each of six substances (barbiturates, opioid [heroin], cocaine, amphetamines, hallucinogens, and cannabis [marijuana]) as well as a summary measure of the six, considering each equally disordered.

Estimation Models

Estimating the economic costs of drug abuse is complex, involving a variety of methods and sources of data that are spelled out in considerable detail in the full report (Rice et al. 1990). This section briefly summarizes the models for estimating the cost of drug abuse for 1985 by type of cost.

Direct Costs. The direct costs of drug abuse are the value of resources that could be allocated to other uses in the absence of drug abuse. Direct costs include the amounts spent for personal health care for persons suffering from drug abuse, including care in drug-related specialty and Federal institutions, short-stay hospital care, and physician and other professional services. Also included are support costs related to the treatment of drug abuse, such as expenditures for research, training costs for physicians and nurses, program administration, and net cost of private insurance. Other related direct costs encompass the costs of crime, including public police protection costs, private legal defense, and property destruction.

In general, the direct costs of drug abuse are estimated as the product of two components: total utilization of services and unit prices or charges. For example, short-stay hospital days of care were obtained from the 1984, 1985, and 1986 NHDS public use tapes. Included are days of care associated with a primary diagnosis of drug abuse and the additional days of care (by age and sex) reported as secondary or comorbid drug abuse diagnoses. Expenses per patient day were applied to these days of care to obtain total short-stay hospital costs. Table 2 summarizes the core costs of drug abuse by type of cost as well as the data sources used.

Other related direct costs of drug abuse include the following components: criminal justice system, drug traffic control, private legal defense, property destruction, and social welfare administration. For each component, the costs attributed to drug abuse are estimated employing the offense-specific methodology developed by Cruze and associates (1981) and Harwood and associates (1984) in which causal factors that represent the proportion of offenses or arrests considered to be due to drug abuse are applied to the number of known offenses and then multiplied by the costs per offense. Table 3 summarizes the other related costs and the data sources used.

TABLE 2.

Core costs of drug abuse by type of cost, 1985

| Type of Cost | Amount (millions) | Percent Distribution | Data Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 10,624 | 100 | |

| Direct Costs | 2,082 | 19.6 | |

ADMa specialty and Federal Institutions |

570 | 5.4 | |

Federal Providers |

176 | 1.7 | Personal Communications with Veterans Administration, Department of Defense, and Indian Health Service |

State and County Psychiatric Providers |

91 | 0.9 | National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) 1988 |

Private psychiatric hospitals |

30 | 0.3 | NIMH 1988 |

Other ADMa Institutions |

273 | 2.6 | NIDA 1983: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism 1983 |

Short-stay hospitals |

1,242 | 11.7 | National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS) 1986-1988; American Hospital Association 1987 |

Other treatment costs |

69 | 0.6 | |

Office-based Physicians |

52 | 0.5 | NCHS 1985a |

Other Professional Services |

17 | 0.2 | Personal communications with American Psychological Association and American Council of Social Workers |

Support Costs |

201 | 1.9 | U.S. Executive Office of the President 1986; Jolly et al. 1986; Klemmer et al. 1987; Health Care Financing Administration 1987 |

| Indirect Costs | 8,542 | 80.4 | |

Morbidity |

5,979 | 56.3 | |

Noninstitutionalized population |

5,943 | 55.9 | NIMH 1980-1985 |

Institutionalized population |

36 | 0.3 | Manderscheld 1988 |

Mortalityb |

2,563 | 24.1 | NCHS 1985b; U.S. Bureau of the Census 1985; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 1986 |

aAlcohol and other drug abuse and mental lllness

bDiscounted at 6 percent

NOTE: Percents may not add to total due to rounding.

TABLE 3. Other related costs of drug abuse by type of cost, 1985

| Type of Cost | Amount ($ millions) | Percent Distribution | Date Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 32,401 | 100.0 | |

Direct Costs |

13,209 | 40.7 | |

Crime |

13,203 | 40.7 | |

Public expenditures |

11,063 | 34.1 | |

Criminal justice |

9,508 | 29.3 | |

Police protection |

5,810 | 17.9 | U.S. Department of Justice 1987a, 1986a |

Legal adjudication |

1,108 | 3.4 | U.S. Department of Jusice 1987a, 1986a |

Correction |

2,500 | 8.0 | U.S. Department of Justice 1987a, 1986b |

Drug traffic control |

1,535 | 4.8 | |

Prevention |

175 | .5 | U.S. Office of Management and Budget 1988 |

Law enforcement |

1,380 | 4.3 | U.S. Office of Management and Budget 1988 |

Private Legal Defense |

1,381 | 4.3 | U.S. Bureau of the Census 1985 |

Property destruction |

759 | 2.3 | U.S. Department of Justice 1987b |

Other direct expendituresa |

6 | b | Blxby 1988 |

Indirect Costs |

19,252 | 59.3 | |

Victims of crime |

842 | 2.6 | US. Department of Justice 1986c and average earnings per day |

Incarceration |

4,434 | 13.7 | U.S. Department of Justice 1985, 1986d, 1087c, 1987a, 1988 and average earnings |

Crime careers |

13,976 | 43.1 | NIDA 1988: U.S. General Accounting Office 1988; Nurco et al. 1985; U.S. Bureau of the Census 1987 |

aSocial welfare expenditures

bLess than one-tenth of 1 percent

NOTE: Percents may not add to total due to rounding.

Morbidity Costs. Morbidity costs, the value of reduced or lost productivity due to drug abuse, are estimated as the product of the number of individuals affected times the average income loss per individual due to drug abuse. Each of these terms is further divided into two parts: (1) The number of drug abusers is the size of the reference population times the drug abuse prevalence rates; and (2) the average income loss per drug abuser is the percentage loss due to the disorder per individual times the average income level the individual would have earned had he or she not been affected by this disorder. Each of these terms is disaggregated by age, sex, and disorder, except average income for persons without these disorders, which can be disaggregated only by age and sex.

The identity is given below:

$LOSS= (POPlj*PREVljk) (bljk*Ylj)

Where:

$LOSS=the aggregate loss in income due to drug abuse POPlj=the size of the population by age and sex

PREVljk=the prevalence rate by age, sex, and disorder bljk=the percentage income loss per individual with drug abuse by age, sex, and disorder

Ylj=the average Income by age and sex for individuals without disorders Summing this four-term product over age, sex, and drug abuse disorder provides an estimate of the aggregate loss of income due to drug abuse among the entire population.

A timing model was developed in the estimation of impairment rates (percent of income loss) that were applied to average incomes, including an imputed value of housekeeping services, by age and sex. Maximum likelihood estimation is employed to estimate impairment rates based on a model that measures the lifetime effect on current income of individuals with these disorders, taking into account the timing and duration of the drug abuse disorders. Timing and duration are based on measures of time of onset and time of last symptom relative to the time of interview. The impairment rates are the adjusted cross-section coefficients obtained when the probability of each observation in the likelihood function is estimated by the integral of the error in the income equation over the reported income interval. The error is equal to the difference between the natural logarithm of personal income and coefficients multiplying lifetime measures of functions of the timing and duration of individual drug abuse disorders and other control variables. Multiplying the impairment rates by average incomes, therefore, yields measures of the annual income loss per individual with the disorder by age, sex, and disorder.

Alcohol and other drug abuse and mental disorders are not neatly segregated among drug abusers who often abuse alcohol and vice versa, and both types of substance abusers have higher than average rates of mental illness (Collins and Schlenger 1983; Grande et al. 1984; Miller et al. 1983; Rachal et al. 1981, 1982; Wolf et al. 1988).

In the larger study, all income losses due to these disorders are distributed among the three categories. The prevalence of multiple disorders in individuals presents a unique problem-namely, how to allocate income loss attributable to multiple disorders among the disorders. This problem was addressed by first determining if measurable interaction effects of overlapping disorders were identifiable. In initial regression studies, multiple diagnostic variables were included to determine if overlapping prevalence introduced additional income loss (over and above that found from first-order prevalence measures).

Because of the colinearity introduced by these additional variables, however, it was not possible to statistically discern such effects. As a result, the analysis assumes that the effects of overlapping prevalence are additive but not interactive. In other words, the impairment rate found for drug abuse is the same whether it is a sole disorder or in the presence of an alcohol and/or a mental disorder.

Mortality Costs. Mortality costs are the value of lost productivity due to premature death resulting from drug abuse. If an individual had not died prematurely, he or she would have continued to be productive for a number of years. The estimated cost or value to society of all deaths is the product of the number of deaths and the expected value of an individual’s future earnings with sex and age taken into account. This method of derivation considers life expectancy for different age and sex groups, changing pattern of earnings at successive ages, varying labor force participation rates, an imputed value for housekeeping services, and the appropriate discount rate to convert a stream of costs into its present worth.

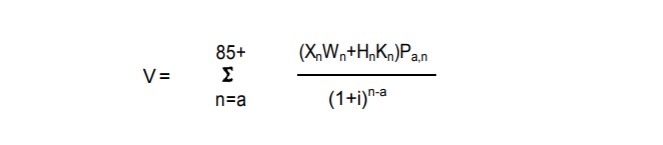

The formula for calculating the present value of lifetime earnings (V) per person is presented below:

a=the midyear age for the given cohort of persons Xn=the annual mean earnings for all persons with earnings in an age group where the midpoint is age n

i=the discount rate

Hn=the annual mean imputed value of housekeeping services for all persons in an age group where the midpoint is age n

Kn=the average housekeeping participation rate in the age group with midpoint age n

Wn=the average labor force participation rate in an age group with midpoint age n

Pa,n=the probability that a person of age a will survive to age n

A discount rate of 8 percent is used to convert the stream of lifetime costs into its present value equivalent, and an average annual increase of 1 percent in the future productivity of wage earners was assumed.

The estimate of lifetime earnings is based on varying labor force participation rates. The assumption is that people will be working and productive during their expected lifetime in accordance with the current pattern of work experience for their sex and age group. The economic variables used for estimating lifetime earnings are shown in table 4.

Output losses are based on annual mean earnings by age and sex adjusted for wage supplements such as employer contributions for social insurance, private pensions, and welfare funds. Cross-sectional profiles of mean earnings by age and sex are employed to estimate lifetime earnings. In applying these data, the future pattern of earnings of an average individual within a sex group is assumed to follow the pattern reported by the U.S. Bureau of the Census (1987) during a base year. The average individual may expect his or her earnings to rise with age and experience in accordance with the cross-sectional data for that year.

Marketplace earnings underestimate the loss resulting from injury because many persons are not in the labor force. Many of these persons, as well as those in the labor force, perform household services. The value of household work, therefore, must be added to earnings. For this study, estimates are developed of hours spent on household labor employing regression analysis to control for socioeconomic and demographic factors (Douglas et al. 1990). The hours are then valued on the basis of 1985 wage rates. The present value of lifetime earnings by age and sex at a 6-percent discount rate are shown in table 5.

TABLE 4.

Selected economic variables used in estimating mortality costs by age and sex, 198

| Percent of Population | With Earnings | Mean Annual | Earnings ($) | Mean Annual Value | Of Housekeeping | Services | ($)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

In | Labor Force | Not In | Labor Force | ||||

| Age Group | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female |

| 15-29 | 44.9 | 41.5 | 6,706 | 6,353 | 1,835 | 4,691 | 3,611 | 9,330 |

| 20-24 | 85.0 | 71.8 | 19,357 | 16,030 | 2,220 | 7,076 | 4,706 | 11,715 |

| 25-29 | 94.1 | 75.5 | 25,771 | 19,702 | 2,604 | 7.862 | 5,091 | 12,396 |

| 30-34 | 94.4 | 74.1 | 30,950 | 22,268 | 2,871 | 8,491 | 5,327 | 13,130 |

| 35-39 | 94.8 | 75.6 | 36,075 | 22,077 | 2,960 | 8,911 | 5,446 | 13,549 |

| 40-44 | 93.5 | 75.4 | 38,856 | 21,642 | 2,989 | 8,282 | 5,475 | 12,920 |

| 45-49 | 93.2 | 73.0 | 38,884 | 21,252 | 2,989 | 7,469 | 5,475 | 12,108 |

| 50-54 | 90.5 | 65.4 | 37,497 | 20,476 | 2,989 | 7,469 | 5,475 | 12,108 |

| 55-59 | 82.0 | 55.7 | 35,936 | 19,878 | 3,196 | 7,338 | 5,682 | 12,029 |

| 60-64 | 62.6 | 40.3 | 35,409 | 19,270 | 3,196 | 7,338 | 5,682 | 12,029 |

| 65-69 | 24.6 | 13.3 | 33,412 | 19,552 | 3,196 | 7,155 | 5,712 | 11,793 |

| 70-74 | 12.9 | 5.5 | 27,896 | 16,529 | 2,276 | 5,094 | 4,067 | 8,397 |

| 74-79 | 8.4 | 3.0 | 23,284 | 13,988 | 1,547 | 3,484 | 2,786 | 5,710 |

| 80-84 | 5.5 | 1.5 | 19,418 | 11,824 | 899 | 2,013 | 1,607 | 3,317 |

| 85+ | 3.5 | 1.0 | 16,212 | 9,999 | 509 | 1,139 | 909 | 1,878 |

aMean annual earnings for year-round, full-time workers, including suppliments, consisting mainly of employer's contributions to social insurance.

bValues are imputed by muitiplying hours spent In each type of domestic activity by the wager for corresponding occupations.

SOURCES: U.S. Bureau of the Census 1985, tables 34 and 36; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 1986. table 3.

AIDS. Drug abuse has contributed to the spread of the human immunodeficiency virus and other sexually transmitted diseases, IV drug users account for about one-fifth of the AIDS cases (Centers for Disease Control 1990). To estimate the cost of AIDS attributed to drug abuse, 20 percent is applied to the total direct and indirect costs of AIDS in 1985 developed by Scitovsky and Rice (1987).

Cost Estimates for 1988. The total cost of drug abuse is updated for 1988 by employing economic data and indexes with known relationships to the drug abuse cost estimates, To obtain the 1988 values, inflationary and real changes are taken into account. Direct costs are adjusted using the percentage change in the components of total personal health care expenditures between 1985 and 1988. These data incorporate inflation in the medical care market as well as the effect of changing demographics and patterns of health care utilization. For indirect costs, inflation and real change are estimated separately. The change in hourly compensation in the business sector is used for inflation; the change in the U.S. civilian labor force is used to reflect real change for morbidity; and the change in the total number of deaths is used to reflect real change for mortality.

TABLE 5. Present value of lifetime earnings ($)a by age and sex, 1985

| Age | Males | Females |

|---|---|---|

| <1 | 208,631 | 173,738 |

| 1-4 | 236,117 | 196,515 |

| 5-9 | 293,977 | 244.559 |

| 10-14 | 374,790 | 311,678 |

| 15-19 | 468,782 | 384,026 |

| 20-24 | 541,021 | 425,804 |

| 25-29 | 568,546 | 424,982 |

| 30-34 | 565,043 | 402,178 |

| 35-39 | 532,289 |

364,873 |

| 40-44 | 471,190 | 319,090 |

| 45-49 | 389,462 | 268,529 |

| 50-54 | 294,646 | 214,826 |

| 55-59 | 194,878 | 159,614 |

| 60-64 | 101,085 | 105,272 |

| 65-69 | 39,713 | 61,103 |

| 70-74 | 17,802 | 33,574 |

| 75-79 | 8,789 | 17,531 |

| 80-84 | 4,457 | 8,655 |

| 85+ | 1,408 | 2,257 |

aCalculations are based on a 6-percent discount rate.

Similarly, for other related crime expenditures, the gross national product implicit price deflator for government purchases of goods and services is used to reflect inflation, and the change in the number of arrests is used for real change. For AIDS, inflation is accounted for by the change in the medical care component of the Consumer Price Index and real change by the significant increase in the number of AIDS cases diagnosed.

RESULTS

The 1985 costs to society of drugs are highlighted below. Crack cocaine addiction and its devastating consequences are not included in the cost estimates because this major public health problem emerged after 1985.

- The total economic costs of drug abuse amount to $44.1 billion in 1985, including direct treatment and support costs (5 percent), indirect morbidity costs (14 percent), indirect mortality costs (6 percent), other related costs (74 percent), and the cost of AIDS (2 percent) (table 6).

TABLE 6. Economic costs of drugs by type of cost, 1985 and 1988

| 1985 | 1988 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of Cost | Amount ($ millions) | Percent Distribution | Amount ($ millions) | Percent Distribution |

| Total | 44,052 | 100.0 | 58,279 | 100.0 |

Core costs |

10,624 | 24.1 | 12,896 | 22.1 |

Direct |

2,082 | 4.7 | 2,656 | 4.6 |

Treatment |

1,881 | 4.3 | 2,407 | 4.1 |

support |

201 | 0.4 | 249 | 0.4 |

Indirect |

8,542 | 19.4 | 10,240 | 17.6 |

Morbidity |

5,979 | 13.6 | 7,194 | 12.3 |

Mortality |

2,583 | 5.8 | 3,046 | 5.2 |

Other related costs |

32,461 | 73.7 | 42,202 | 72.4 |

Direct |

13,209 | 30.0 | 18,782 | 28.8 |

Indirect |

19,252 | 43.7 | 25,420 | 43.8 |

AIDS |

967 | 2.2 | 3,181 | 5.6 |

aCalculations are based on a 6-percent discount rate.

- Direct costs of drug abuse amount to $2.1 billion for 1985. Of this total, three-fifths are for short-stay hospital care of persons with primary and secondary diagnoses of drug abuse.

- Private sources account for 36 percent of the $2.1 billion direct costs for treatment and support of drug abusers; 64 percent is borne by public sources-39 percent from Federal funds and 25 percent from State and local sources (table 7).

TABLE 7. Drug abuse core direct costs by treatment setting and source of payment, 1985

| Amount ($ millions) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment Setting | Total | State and Federal | Local | Private |

| Total | 2,082 | 806 | 517 | 759 |

| ADMb specialty and Federal institutions |

570 | 233 | 298 | 39 |

Federal providers |

178 | 178 | - | - |

State and county psychiatric hospitals |

91 | 13 | 74 | 4 |

Private psychiatric hospitals |

30 | 4 | 3 | 23 |

Other ADM institutions |

273 | 40 | 221 | 12 |

| Other treatment costs | 1,311 | 509 | 204 | 598 |

Short-stay hospitals |

1,242 | 504 | 202 | 538 |

Office-based physicians |

52 | 4 | 1 | 47 |

Other professional services Nursing homes Drugs |

17 | 1 | 1 | 15 |

| Support costs |

201 | 64 | 15 | 122 |

aIncludes prlvate health insurance, direct payments by patients, and philanthropy

bAlcohol and other drug abuse and mental Illness

- Drug abuse morbidity costs, the value of reduced or lost productivity, amount to $6 billion based on a prevalence rate of 3.6 percent among adults ages 18 to 64, or 5.2 million persons, and 1,775 residents In mental facilities suffering from this disorder. Prevalence is based on a diagnostic measure, defined in terms of clinical criteria for a medical diagnosis of drug abuse or dependence. People who use marijuana, hashish, cocaine, and other illicit drugs without clinical manifestations of drug abuse or dependence and without meeting severity criteria are not included here.

- More than 6,100 deaths in 1965 are attributed to drug abuse, representing 231,000 person years lost, or 37.6 years per death and a loss of $2.6 billion to the economy at a 6-percent discount rate, or $416,657 per death (table 6).

TABLE 8. Drug abuse mortality: number of deaths, person years lost, and productivity Iosses by age and sex, 1985

| Age and Sex | Number of Deaths | Person Years Lost Number (thousands) | Per Death | Productivity amount (millions) | Losses ($)a Per Death |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both Sexes | 6,118 | 231 | 37.8 | 2,583 | 418,857 |

| <15 | 61 | 4 | 71.5 | 14 | 238,244 |

| 15-24 | 581 | 30 | 53.9 | 277 | 492,928 |

| 25-44 | 4,007 | 169 | 42.1 | 2,049 | 511,452 |

| 45-84 | 885 | 22 | 25.4 | 209 | 241,696 |

| 65+ | 824 | 6 | 10.2 | 13 | 21,108 |

| Males | 4,290 | 182 | 37.9 | 2,050 | 477,989 |

| <15 | 30 | 2 | 88.5 | 8 | 252,967 |

| 15-24 | 383 | 20 | 51.7 | 203 | 529,138 |

| 25-44 | 3,108 | 127 | 40.8 | 1,700 | 547,389 |

| 45-84 | 485 | 11 | 23.5 | 135 | 278,883 |

| 65+ | 288 | 3 | 9.2 | 5 | 17,111 |

| Females | 1,828 | 69 | 37.7 | 512 | 280,132 |

| <15 | 31 | 2 | 74.4 | 7 | 220,080 |

| 15-24 | 178 | 10 | 58.7 | 74 | 415,007 |

| 25-44 | 901 | 42 | 48.5 | 349 | 387,585 |

| 45-84 | 380 | 11 | 27.7 | 74 | 194,514 |

| 55+ | 338 | 4 | 11.1 | 8 | 24,487 |

aCalculations are based on a d-percent discount rate.

NOTE: Numbers may not add to totals due to rounding.

- About three-fourths of drug abuse deaths occur among persons ages 15 to 44 years. This age group accounts for 66 percent of the person years lost and 91 percent of the mortality costs of drug abuse.

- Core costs (direct and indirect health-related costs) account for $10.6 billion. Adults ages 15 to 44 account for two-thirds of the total core costs. The cost for men is almost twice that for women-$6.9 billion compared with $3.7 billion (table 9).

- The major cost component for drug abuse is other related costs, amounting to $32.5 billion and constituting almost three-fourths of the total economic costs of drug abuse. Direct crime expenditures amount to $13.2 billion, two-fifths of the other related costs. Crime expenditures include public police protection costs, private legal defense, and property destruction.

TABLE 9. Core costs of drug abuse by age and sex, 1985

| Age and Sex | Amount ($ millions) | Percent Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 10,624 | 100.0 |

| <15a | 96 | 0.9 |

| 15-44 | 7,216 | 67.9 |

| 45-64 | 3,015 | 26.4 |

| 65+ | 295 | 2.6 |

| Males | 6,953 | 100.0 |

| <15a | 57 | 0.8 |

| 15-44 | 4,977 | 71.6 |

| 45-64 | 1,792 | 25.6 |

| 65+ | 127 | 1.6 |

| Females | 3,671 | 100.0 |

| <15a | 41 | 1.1 |

| 15-44 | 2,239 | 61 .0 |

| 45-64 | 1,223 | 33.3 |

| 65+ | 168 | 4.5 |

aThe <15 age group includes costs for 15-to 17-year-old persons for several cost categories (including alcohol and other drug abuse and mental illness specialty institutions and Federal providers); thus, the costs for the <15 age group are overstated and the costs for the 15 to 44 age groups are correspondingly understated.

- Other related costs also include the value of productivity losses for those who, as a result of heroin or cocaine addiction, engage in crime as a career rather than in legal employment. These productivity losses are estimated at $14 billion. In addition, the productivity losses of people incarcerated in prisons as a result of conviction of a drug-related crime are estimated at $4.4 billion.

- The direct and indirect costs of AIDS associated with IV drug users is estimated at almost $1 billion. Of this total, indirect costs constituting four-fifths of the total, mainly due to high mortality among persons with AIDS.

- The total cost of drug abuse is estimated at $58.3 billion for 1988 (table 6).

LIMITATIONS

The cost estimates presented in this study are based on the most current and reliable data available and new methodology developed specifically for this study. Nonetheless, several qualifications are in order.

Several known costs are excluded because data are unavailable. No attempt is made to capture the costs of pain and suffering, and no attempt is made to value the services of family members and friends who care for drug abusers. This “informal care” cost is likely to be significant, but there are no reliable data from which to make estimates.

Some of the cost estimates are likely to be low, again due to data limitations. For example, hospital discharge data records may not list drug abuse diagnoses because of the stigma associated with this disorder (Gfroerer et al. 1988). In one study, physicians identified only 40 percent of patients who suffered from alcohol or other drug abuse (Coulehan et al. 1987). To compensate for the probable omission of hospitalization of some drug abusers, we use average expense per patient day in all non-Federal community hospitals applied to the reported days of care to obtain total hospital costs. Because most drug abuse short-stay hospital episodes do not involve surgery, the average expense per day for drug abuse patients is probably less than for the average patient, which is likely to overestimate the costs.

No estimates are made for drug abuse income loss among the transient and the military populations, resulting in underestimation of costs. Estimates of income loss among the civilian noninstitutionalized resident population are calculated only for ages 18 to 64. To the degree that those younger than age 18 and older than 64 suffer earnings losses due to drug abuse, the costs are understated.

Productivity losses are based on personal income rather than personal earnings, Personal income, which includes receipt of transfer payments, may be less sensitive to the effects of drug abuse than personal earnings, resulting in possible understatement of costs.

A d-percent discount rate is employed to estimate the present value of future earnings lost. Use of a lower discount rate would yield higher mortality costs.

Using the d-percent discount rate results in low estimates of mortality costs.

Full-time, year-round earnings for the civilian noninstitutionalized population and average life expectancy are used in the estimates of forgone earnings. These measures should be adjusted to reflect earnings and life expectancy without drug abuse, but data are not available to make these adjustments, thereby introducing a downward bias into the estimates.

For these reasons, the cost estimates presented in this study can be interpreted as a lower limit of the true cost of drug abuse. As better data become available, the approach can be refined and improved.

CONCLUSIONS

The measurable economic costs of drug abuse are high, amounting to $44.1 billion in 1985 and an estimated $58.3 billion for 1988. Each year an estimated 2 million individuals are hospitalized, and 125,000 visits with a drug abuse diagnosis are made to office-based physicians. In 1985 more than 6,100 deaths are attributed to drug abuse, of which three-fourths occur among persons 15 to 44 years of age, representing 231,000 person years lost, or 37.8 years per death.

The cost to society of crime estimated to be due to drug abuse is exceedingly high, amounting to $32.5 billion, almost three-fourths of the total economic costs of drug abuse. Included are expenditures for police protection, private legal defense, and property destruction as well as the value of productivity losses for those who engage in crime as a career as a result of heroin or cocaine addiction and for people incarcerated in prison as a result of conviction of a drug-related crime.

In light of these high costs, more attention must be directed at comprehensive research-based strategies to reduce drug abuse in the United States. In January 1990 President Bush announced a coordinated and comprehensive National Drug Control Strategy to make drugs undesirable and difficult to obtain through a mix of supply and demand policies by using all the drug reduction tools at hand: criminal justice systems; drug treatment programs; prevention activities in schools, businesses, and communities; international efforts aimed at drug source countries; interdiction strategies; and a variety of intelligence and research resources (Office of National Drug Control Policy 1990). Special attention should be given to improvement of data collection, analysis, and evaluation to provide reliable and timely information for policy use. These expanded data efforts will enable the conduct of services research studies to better estimate the economic costs to society of drug abuse.

Acton, J.D. Measuring the Social Impact of Heart and Circulatory Disease Programs: Preliminary Framework and Estimates. Rand Report R-1967.

Santa Monica, CA: The Rand Corporation, 1975.

American Hospital Association. Hospital Statistics. 1987 ed. Chicago: American Hospital Association, 1987.

Bixby, A.K. Public social welfare expenditures, fiscal year 1985. Soc Sec Bull 51(4):21-31, 1988.

Centers for Disease Control. HIV/AIDS Surveillance. Altanta, GA: Center for Infectious Diseases, 1990.

Collins, J., and Schlenger, W.E. The Prevalence of Psychiatric Disorder Among Admissions to Prison. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute, 1983.

Committee on Ways and Means. The Enemy Within: Crack-Cocaine and American Families. U.S. House of Representatives, Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1990.

Coulehan, J.L.; Zettler-Segal, M.; Block, M.; McClelland, M.; and Schuiberg, H.C. Recognition of alcoholism and substance abuse in primary care patients. Arch Intern Med 147:349-352, 1987.

Cruze, A.M.; Harwood, H.J.; Kristiansen, P.C.; Collins, J.J.; and Jones, D.C. Economic Costs to Society of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Mental Illness, 1977. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute, 1981.

Douglas, J.B.; Kenney, G.M.; and Miller, T. Which estimates of household production are best? J Forensic Econ 4:25-45, 1990.

Gfroerer, J.C.; Adams, E.H.; and Moien, M. Drug abuse discharges from non-federal short-stay hospitals. Am J Public Health 78(12):1559-1562, 1988.

Grande, T.P.; Wolf, A.W.; Schubert, D.S.; Patterson, M.B.; and Brocco, K. Associations among alcoholism, drug abuse, and antisocial personality: A review of the literature. Psychol Rep 55:455-474, 1984.

Harwood, H.J.; Napolitano, D.M.; Kristiansen, P.; and Collins, J.J. Economic Costs to Society of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Mental Illness: 1980.

Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute, 1964.

Health Care Financing Administration. National health expenditures, 1986-2000. Health Care Financing Rev 8:1-36, 1987.

Hodgson, T.A. The state of the art of cost-of-illness estimates. Adv Health Econ Health Serv Res 4:129-164, 1983.

Hodgson, T.A., and Meiners, M. Cost-of-illness methodology: A guide to current practices and procedures. Milbank Q 60(3):429-462, 1982.

Jolly, P.; Taksel, L.; and Baime, D. US. medical school finances. JAMA 256(12):1570-1580, 1986.

Klemmer, K.; Bednash, G.; and Redman, B. Cost model for baccalaureate nursing education. J Prof Nurs 3(3):176-189, 1987.

Manderscheid, R.W. “Resident Patients in State and County Mental Hospitals by Mental Disorder, Sex, and Age, by State, United States, 1985.” Rockville, MD: National Institute of Mental Health, 1988 (unpublished tabulations).

Miller, J.; Cisin, I.; Gardner-Keaton, H.; Harrell, A.; Wirtz, P.; Abelson, H.; and Fishburne, P. National Survey on Drug Abuse: Main Findings 1982.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, 1983.

National Center for Health Statistics. Unpublished data from public use tapes, National Ambulatory Care Survey, 1985. Hyattsville, MD: US. Department of Health and Human Services, 1985a.

National Center for Health Statistics. Unpublished data from public use tapes, National Mortality Detail File, 1985. Hyattsville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1985b.

National Center for Health Statistics. Unpublished data from public use tapes, National Hospital Discharge Survey, 1984-1986. Hyattsville, MD: US Department of Health and Human Services, 1986-1988.

National Institute of Mental Health. Unpublished data from public use tapes, Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Surveys, 1980-1985. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, 1980-1985.

National Institute of Mental Health. Specialty mental health organizations: United States, 1985. Mental Health Statistical Note No. 189. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1988.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. National Drug and Alcohol Abuse Treatment Utilization Survey, 1982. Rockviile, MD: US. Department of Health and Human Services, 1983.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. Main Findings for Drug Abuse Treatment Units, September 1982: Data From the National Drug and Alcoholism Treatment Utilization Survey (NDATUS). Series F, No. 10. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, 1983.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Main Findings 1985. DHHS Pub. No. (ADM)88-156. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, 1988.

National Institute on Drug Abuse. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Highlights. 1988. DHHS Pub. No. (ADM)90-1681. Rockville, MD: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, 1990.

Nurco, D.N.; Cisin, I.H.; and Bail, J.C. Crime as a source of income for narcotic addicts. J Subst Abuse Treat 2:113-115, 1985.

Office of National Drug Control Policy. National Drug Control Strategy. 252-692/01157. Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1990.

Rachal, J.V.; Hubbard, R.L.; Cavanaugh, E.R.; Bray, R.; Collins, J.; Allison, M.; and Craddock, G. Characteristics, Behaviors and Intreatment Outcomes of Clients in TOPS-1979 Admission Cohort. Research Triangle Park, NC: Research Triangle Institute, 1981.

Rachal, J.V.; Maisto, S.A.; Guess, L.L.; and Hubbard, R.L. Alcohol Consumption and Related Problems. National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Alcohol and Health Monograph 1. DHHS Pub. No. (ADM)82-1190. Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., US. Govt. Print. Off., 1982.

Rice, D.P.; Keiman, S.; Miller, L.B.; and Dunmeyer, S. The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Mental Illness: 1985. Report submitted to the Office of Financing and Coverage Policy of the Alcohol, Drug Abuse, and Mental Health Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. DHHS Pub. No. (ADM)90-1694. San Francisco, CA: Institute for Health & Aging, University of California, 1990.

Rice, D.P.; MacKenzie, E.J.; and Associates. Cost of Injury in the United States: A Report to Congress. San Francisco, CA: Institute for Health & Aging, University of California and Injury Prevention Center, The Johns Hopkins University, 1989. pp. 101-109.

Schelling, T.C. The life you save may be your own. In: Chase, S.B., ed. Problems in Public Expenditure Analysis. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, 1968.

Scitovsky, A.A. Estimating the direct cost of illness. Milbank Q 60(3):463-491, 1982.

Scitovsky, A.A., and Rice, D.P. Estimates of the direct and indirect cost of acquired lmmunodeficiency syndrome in the United States, 1985, 1986, and 1991. Public Health Rep 102(1):5-17, 1987.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Employment and Earnings. Table 3. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Labor, 1986.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Census of Service Industries, 1982. Tables 34 and 36. Washington, DC: US. Department of Commerce, 1985. pp. 1-117.

U.S. Bureau of the Census. Money income of households, families, and persons in the United States, 1985. Current Population Reports. Series P-60, No. 156. Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1987.

US. Department of Justice. Jail Inmates, 1983. Bulletin NCJ-99175. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1985. p. 4.

U.S. Department of Justice. Criminal Victimization in the United States in 1985. Bulletin NCJ-102534. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1986c.

US. Department of Justice. Crime in the United States, 1985: Uniform Crime Reports. Washington, DC: Federal Bureau of Investigation, 1986a.

US. Department of Justice. Prisoners in 1985. Bulletin NCJ-101384. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1986d. p. 2.

U.S. Department of Justice. Sourcebook of Criminal Justice Statistics. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1986b.

U.S. Department of Justice. Criminal Victimization in the United States, 1985: A National Crime Survey Report. Bulletin NCJ-104273. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1987b.

US. Department of Justice. Jail Inmates, 1986. Bulletin NCJ-107123. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1987c.

U.S. Department of Justice. Justice Expenditure and Employment, 1985. Bulletin NCJ-104460. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1987a.

U.S. Department of Justice. Profile of State Prison Inmates, 1986. Bulletin NCJ-109926. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics, 1988.

U.S. Executive Office of the President. Budget of the United States Government, 1987-Appendix. Washington, DC: Supt. of Docs., U.S. Govt. Print. Off., 1986.

U.S. General Accounting Office. Controlling Drug Abuse: A Status Report, GAO/GGD 88-39. Washington, DC: U.S. General Accounting Office, 1988.

US. Office of Management and Budget. Federal Drug Law Enforcement and Abuse Summary-1981 to 1989. Washington, DC: US. Executive Office of the President, 1988.

Wolf, A.W.; Schubert, D.J.; Patterson, M.B.; Grande, T.P.; Brocco, K.J.; and Pendleton, L. Associations among major psychiatric diagnoses. J Consult Clin Psychol 56(2):292-294, 1988.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This chapter is based on research conducted for the Financing and Services Research Branch, Division of Applied Research, National Institute on Drug Abuse (contract no. 283-87-0007) and titled The Economic Costs of Alcohol and Drug Abuse and Mental Illness: 1985.

The authors acknowledge the contributions of Sarah Dunmeyer for her research assistance on the costs indirectly related to the treatment and lost productivity of drug abusers and to Scott Hood for computer and statistical assistance.

AUTHORS

Dorothy P. Rice, Sc.D. (Hon.) Professor University of California, San Francisco School of Nursing San Francisco, CA 94143

Sander Kelman, Ph.D. Research Economist New Jersey Division of Medical Assistance and Health Services Trenton, NJ 08625

Leonard S. Miller, Ph.D. Professor University of California, Berkeley School of Social Welfare Berkeley, CA 94720

Economic Cost of Illicit Drug Studies: Critique and Research Agenda

Jody L. Sindelar

Retrieved from https://archives.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/monograph113.pdf on 08/06/2020

file:///C:/Users/Mark%20VanderMeer/Downloads/Grim_et_al-2019-Journal_of_Religion_and_Health.pdf

Either click on the link above or copy and paste into your browser to access the link. Read all 38 pages of this document.