Textbook Reading: Northouse Chapter 1 & 2

Introduction

Leadership is a highly sought-after and highly valued commodity. In the 15 years since the first edition of this book was published, the public

has become increasingly captivated by the idea of leadership. People continue to ask themselves and others what makes good leaders. As individuals, they seek more information on how to become effective leaders. As a result, bookstore shelves are filled with popular books about leaders and advice on how to be a leader. Many people believe that leadership is a way to improve their personal, social, and professional lives. Corporations seek those with leadership ability because they believe they bring special assets to their organizations and, ultimately, improve the bottom line. Academic institutions throughout the country have responded by providing programs in leadership studies.

In addition, leadership has gained the attention of researchers worldwide. A review of the scholarly studies on leadership shows that there is a wide variety of different theoretical approaches to explain the complexities of the leadership process (e.g., Bass, 1990; Bryman, 1992; Bryman, Collinson, Grint, Jack- son, & Uhl-Bien, 2011; Day & Antonakis, 2012; Gardner, 1990; Hickman, 2009; Mumford, 2006; Rost, 1991). Some researchers conceptualize leadership as a trait or as a behavior, whereas others view leadership from an information-processing perspective or relational standpoint. Leadership has been studied using both qualitative and quantitative methods in many contexts, including small groups, therapeutic groups, and large organizations. Collectively, the research findings on leadership from all of these areas provide a picture of a process that is far more sophisticated and complex than the often- simplistic view presented in some of the popular books on leadership.

This book treats leadership as a complex process having multiple dimensions. Based on the research literature, this text provides an in-depth description and application of many different approaches to leadership. Our emphasis is on how theory can inform the practice of leadership. In this book, we describe each theory and then explain how the theory can be used in real situations.

There are many ways to finish the sentence “Leadership is . . .” In fact, as Stogdill (1974, p. 7) pointed out in a review of leadership research, there are almost as many different definitions of leadership as there are people who have tried to define it. It is much like the words democracy, love, and peace. Although each of us intuitively knows what we mean by such words, the words can have different meanings for different people. As Box 1.1 shows, scholars and practitioners have attempted to define leadership for more than a century without universal consensus.

Box 1.1 The Evolution of Leadership Definitions

While many have a gut-level grasp of what leadership is, putting a definition to the term has proved to be a challenging endeavor for scholars and practitioners alike. More than a century has lapsed since leadership became a topic of academic introspection, and definitions have evolved continuously during that period. These definitions have been influenced by many factors from world affairs and politics to the perspectives of the discipline in which the topic is being studied. in a seminal work, Rost (1991) analyzed materials written from 1900 to 1990, finding more than 200 different definitions for leadership. his analysis provides a succinct history of how leadership has been defined through the last century:

1900–1929

Definitions of leadership appearing in the first three decades of the 20th century emphasized control and centralization of power with a common theme of domination. For example, at a conference on leadership in 1927, leadership was defined as “the ability to impress the will of the leader on those led and induce obedience, respect, loyalty, and cooperation” (Moore, 1927, p. 124).

1930'sTraits became the focus of defining leadership, with an emerging view of leadership as influence rather than domination. Leadership was also identified as the interaction of an individual’s specific personality traits with those of a group; it was noted that while the attitudes and activities of the many may be changed by the one, the many may also influence a leader.1940's

The group approach came into the forefront with leadership being defined as the behavior of an individual while involved in directing group activities (hemphill, 1949). at the same time, leadership by persuasion was distinguished from “drivership” or leadership by coer- cion (copeland, 1942).

1950s

Three themes dominated leadership definitions during this decade:

· continuance of group theory, which framed leadership as what leaders do in groups;

· leadership as a relationship that develops shared goals, which

defined leadership based on behavior of the leader; and

· effectiveness, in which leadership was defined by the ability to influence overall group effectiveness.

1960s

although a tumultuous time for world affairs, the 1960s saw harmony amongst leadership scholars. The prevailing definition of leadership as behavior that influences people toward shared goals was under- scored by seeman (1960) who described leadership as “acts by persons which influence other persons in a shared direction” (p. 53).

1970s

The group focus gave way to the organizational behavior approach, where leadership became viewed as “initiating and maintaining groups or organizations to accomplish group or organizational goals” (Rost, 1991, p. 59). Burns’s (1978) definition, however, was the most important concept of leadership to emerge: “Leadership is the reciprocal process of mobilizing by persons with certain motives and values, various eco-nomic, political, and other resources, in a context of competition and conflict, in order to realize goals independently or mutually held by both leaders and followers” (p. 425).

1980s

This decade exploded with scholarly and popular works on the nature of leadership, bringing the topic to the apex of the academic and public consciousnesses. as a result, the number of definitions for leadership became a prolific stew with several persevering themes:

· do as the leader wishes. Leadership definitions still predomi- nantly delivered the message that leadership is getting followers to do what the leader wants done.

· Influence. probably the most often used word in leadership definitions of the 1980s, influence was examined from every angle. in an effort to distinguish leadership from manage- ment, however, scholars insisted that leadership is noncoercive influence.

· Traits. spurred by the national best seller In Search of Excellence (peters & Waterman, 1982), the leadership-as-excellence move- ment brought leader traits back to the spotlight. as a result, many people’s understanding of leadership is based on a trait orientation.

· Transformation. Burns (1978) is credited for initiating a move- ment defining leadership as a transformational process, stating that leadership occurs “when one or more persons engage with others in such a way that leaders and followers raise one another to higher levels of motivation and morality” (p. 83).

Into the 21st Century

Debate continues as to whether leadership and management are separate processes, but emerging research emphasizes the process of leadership, whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal, rather than developing new ways of defining leadership. among these emerging leadership approaches are

· authentic leadership, in which the authenticity of leaders and their leadership is emphasized;

· spiritual leadership, which focuses on leadership that utilizes

values and sense of calling and membership to motivate followers;

· servant leadership, which puts the leader in the role of servant, help these followers become more autonomous, knowledge- able, and like servants themselves; and

· adaptive leadership, in which leaders encourage followers to adapt by confronting and solving problems, challenges, and changes.

after decades of dissonance, leadership scholars agree on one thing: They can’t come up with a common definition for leadership. Because of such factors as growing global influences and generational differences, leadership will continue to have different meanings for different people. The bottom line is that leadership is a complex con- cept for which a determined definition may long be in flux.

Ways of Conceptualizing Leadership

In the past 60 years, as many as 65 different classification systems have been developed to define the dimensions of leadership (Fleishman et al., 1991). One such classification system, directly related to our discussion, is the scheme proposed by Bass (1990, pp. 11–20). He suggested that some defini- tions view leadership as the focus of group processes. From this perspective, the leader is at the center of group change and activity and embodies the will of the group. Another set of definitions conceptualizes leadership from a per- sonality perspective, which suggests that leadership is a combination of special traits or characteristics that some individuals possess. These traits enable those individuals to induce others to accomplish tasks. Other approaches to leadership define it as an act or a behavior—the things leaders do to bring about change in a group.

In addition, some define leadership in terms of the power relationship that exists between leaders and followers. From this viewpoint, leaders have power that they wield to effect change in others. Others view leadership as a transformational process that moves followers to accomplish more than is usually expected of them. Finally, some scholars address leadership from a skills perspective. This viewpoint stresses the capabilities (knowledge and skills) that make effective leadership possible.

Definition and Components

Despite the multitude of ways in which leadership has been conceptualized, the following components can be identified as central to the phenomenon:

(a) Leadership is a process, (b) leadership involves influence, (c) leadership occurs in groups, and (d) leadership involves common goals. Based on these components, the following definition of leadership is used in this text:

Leadership is a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal.

Defining leadership as a process means that it is not a trait or characteristic that resides in the leader, but rather a transactional event that occurs between the leader and the followers. Process implies that a leader affects and is affected by followers. It emphasizes that leadership is not a linear, one-way event, but rather an interactive event. When leadership is defined in this manner, it becomes available to everyone. It is not restricted to the formally designated leader in a group.

Leadership involves influence. It is concerned with how the leader affects followers. Influence is the sine qua non of leadership. Without influence, leadership does not exist.

Leadership occurs in groups. Groups are the context in which leadership takes place. Leadership involves influencing a group of individuals who have a common purpose. This can be a small task group, a community group, or a large group encompassing an entire organization. Leadership is about one individual influencing a group of others to accomplish common goals. Oth- ers (a group) are required for leadership to occur. Leadership training pro- grams that teach people to lead themselves are not considered a part of leadership within the definition that is set forth in this discussion.

Leadership includes attention to common goals. Leaders direct their energies toward individuals who are trying to achieve something together. By common, we mean that the leaders and followers have a mutual purpose. Attention to common goals gives leadership an ethical overtone because it stresses the need for leaders to work with followers to achieve selected goals. Stressing mutuality lessens the possibility that leaders might act toward followers in ways that are forced or unethical. It also increases the possibility that leaders and followers will work together toward a common good (Rost, 1991).

Throughout this text, the people who engage in leadership will be called leaders, and those toward whom leadership is directed will be called followers. Both leaders and followers are involved together in the leadership process. Leaders need followers, and followers need leaders (Burns, 1978; Heller & Van Til, 1983; Hollander, 1992; Jago, 1982). Although leaders and followers are closely linked, it is the leader who often initiates the relationship, creates the communication linkages, and carries the burden for maintaining the relationship.

In our discussion of leaders and followers, attention will be directed toward follower issues as well as leader issues. Leaders have an ethical responsibility to attend to the needs and concerns of followers. As Burns (1978) pointed out, discussions of leadership sometimes are viewed as elitist because of the implied power and importance often ascribed to leaders in the leader- follower relationship. Leaders are not above or better than followers. Leaders and followers must be understood in relation to each other (Hollander, 1992) and collectively (Burns, 1978). They are in the leadership relationship together—and are two sides of the same coin (Rost, 1991).

Leadership Described

In addition to definitional issues, it is important to discuss several other questions pertaining to the nature of leadership. In the following section, we will address questions such as how leadership as a trait differs from leadership as a process; how appointed leadership differs from emergent leadership; and how the concepts of power, coercion, and management dif- fer from leadership.

Trait Versus Process Leadership

We have all heard statements such as “He is born to be a leader” or “She is a natural leader.” These statements are commonly expressed by people who take a trait perspective toward leadership. The trait perspective suggests that certain individuals have special innate or inborn characteristics or qualities that make them leaders, and that it is these qualities that differentiate them from nonleaders. Some of the personal qualities used to identify leaders include unique physical factors (e.g., height), personality features (e.g., extra- version), and other characteristics (e.g., intelligence and fluency; Bryman, 1992). In Chapter 2, we will discuss a large body of research that has exam- ined these personal qualities.

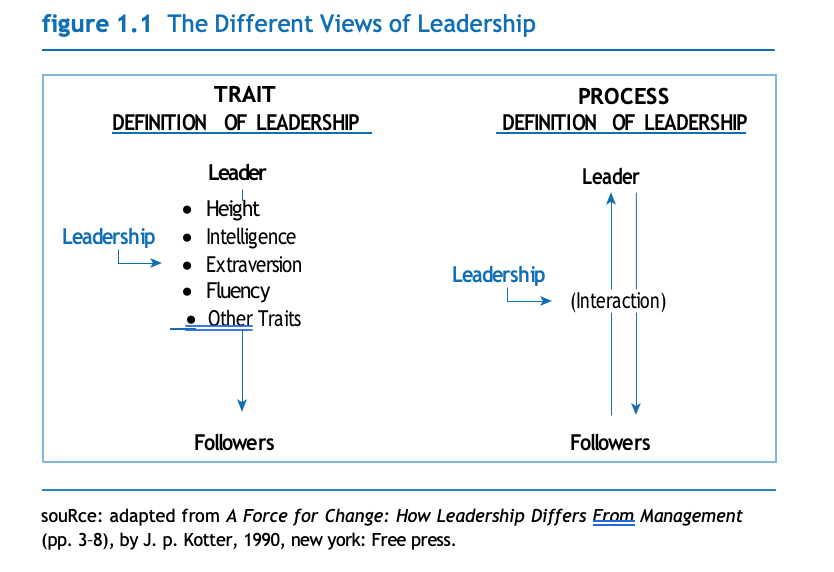

To describe leadership as a trait is quite different from describing it as a process (Figure 1.1). The trait viewpoint conceptualizes leadership as a prop- erty or set of properties possessed in varying degrees by different people ( Jago, 1982). This suggests that it resides in select people and restricts lead- ership to those who are believed to have special, usually inborn, talents.

The process viewpoint suggests that leadership is a phenomenon that resides in the context of the interactions between leaders and followers and makes leadership available to everyone. As a process, leadership can be observed in leader behaviors ( Jago, 1982), and can be learned. The process definition of leadership is consistent with the definition of leadership that we have set forth in this chapter.

Assigned Versus Emergent Leadership

Some people are leaders because of their formal position in an organization, whereas others are leaders because of the way other group members respond to them. These two common forms of leadership are called assigned leader- ship and emergent leadership. Leadership that is based on occupying a posi- tion in an organization is assigned leadership. Team leaders, plant managers, department heads, directors, and administrators are all examples of assigned leadership.

Yet the person assigned to a leadership position does not always become the real leader in a particular setting. When others perceive an individual as the most influential member of a group or an organization, regardless of the individual’s title, the person is exhibiting emergent leadership. The individual acquires emergent leadership through other people in the organization who support and accept that individual’s behavior. This type of leadership is not assigned by position; rather, it emerges over a period through communication. Some of the positive communication behaviors that account for successful leader emergence include being verbally involved, being informed, seeking others’ opinions, initiating new ideas, and being firm but not rigid (Fisher, 1974).

In addition to communication behaviors, researchers have found that per- sonality plays a role in leadership emergence. For example, Smith and Foti (1998) found that certain personality traits were related to leadership emer- gence in a sample of 160 male college students. The individuals who were more dominant, more intelligent, and more confident about their own per- formance (general self-efficacy) were more likely to be identified as leaders by other members of their task group. Although it is uncertain whether these findings apply to women as well, Smith and Foti suggested that these three traits could be used to identify individuals perceived to be emergent leaders.

Leadership emergence may also be affected by gender-biased perceptions. In a study of 40 mixed-sex college groups, Watson and Hoffman (2004) found that women who were urged to persuade their task groups to adopt high-quality decisions succeeded with the same frequency as men with identical instructions. Although women were equally influential leaders in their groups, they were rated significantly lower than comparable men were on leadership. Furthermore, these influential women were also rated as significantly less likable than comparably influential men were. These results suggest that there continue to be barriers to women’s emergence as leaders in some settings.

A unique perspective on leadership emergence is provided by social identity theory (Hogg, 2001). From this perspective, leadership emergence is the degree to which a person fits with the identity of the group as a whole. As groups develop over time, a group prototype also develops. Individuals emerge as leaders in the group when they become most like the group prototype. Being similar to the prototype makes leaders attractive to the group and gives them influence with the group.

The leadership approaches we discuss in the subsequent chapters of this book apply equally to assigned leadership and emergent leadership. When a person is engaged in leadership, that person is a leader, whether leadership

Table 1.1 six Bases of power

referent power Based on followers’ identification and liking for the leader. A teacher who is adored by students has referent power.

expert power Based on followers’ perceptions of the leader’s competence. A tour guide who is knowledgeable about a foreign country has expert power.

Legitimate power Associated with having status or formal job authority. A judge who administers sentences in the courtroom exhibits legitimate power.

reward power Derived from having the capacity to provide rewards to others. A supervisor who gives rewards to employees who work hard is using reward power.

Coercive power Derived from having the capacity to penalize or punish others.

A coach who sits players on the bench for being late to practice is using coercive power.

Information power

Derived from possessing knowledge that others want or need. A boss who has information regarding new criteria to decide employee promotion eligibility has information power.

souRce: adapted from “The Bases of social power,” by J. R. French Jr. and B. Raven, 1962, in

D. cartwright (ed.), Group Dynamics: Research and Theory (pp. 259–269), new york: harper & Row; and “social influence and power,” by B. h. Raven, 1965, in i. D. steiner & M. Fishbein (eds.), Current Studies in Social Psychology (pp. 371–382), new york: holt, Rinehart, & Winston.

was assigned or emerged. This book focuses on the leadership process that occurs when any individual is engaged in influencing other group members in their efforts to reach a common goal.

Leadership and Power

The concept of power is related to leadership because it is part of the influence process. Power is the capacity or potential to influence. People have power when they have the ability to affect others’ beliefs, attitudes, and courses of action. Judges, doctors, coaches, and teachers are all examples of people who have the potential to influence us. When they do, they are using their power, the resource they draw on to effect change in us.

Although there are no explicit theories in the research literature about power and leadership, power is a concept that people often associate with leadership. It is common for people to view leaders (both good and bad) and people in positions of leadership as individuals who wield power over others, and as a result, power is often thought of as synonymous with leadership. In addition, people are often intrigued by how leaders use their power. Studying how famous leaders, such as Hitler or Alexander the Great, use power to effect change in others is titillating to many people because it underscores that power can indeed effectuate change and maybe if they had power they too could effectuate change. But regardless of people’s general interest in power and leadership, power has not been a major variable in theories of leadership. Clearly, it is a component in the overall leadership process, but research on its role is limited.

In her recent book, The End of Leadership (2012), Kellerman argues there has been a shift in leadership power during the last 40 years. Power used to be the domain of leaders, but that is diminishing and shifting to followers. Changes in culture have meant followers demand more from leaders, and leaders have responded. Access to technology has empowered followers, given them access to huge amounts of information, and made leaders more transparent. The result is a decline in respect of leaders and leaders’ legitimate power. In effect, followers have used information power to level the playing field. Power is no longer synonymous with leadership, and in the social contract between leaders and followers, leaders wield less power, according to Kellerman.

In college courses today, the most widely cited research on power is French and Raven’s (1959) work on the bases of social power. In their work, they conceptualized power from the framework of a dyadic relationship that included both the person influencing and the person being influenced. French and Raven identified five common and important bases of power—referent, expert, legitimate, reward, and coercive—and Raven (1965) identified a sixth, information power (Table 1.1). Each of these bases of power increases a lead- er’s capacity to influence the attitudes, values, or behaviors of others.

In organizations, there are two major kinds of power: position power and personal power. Position power is the power a person derives from a particular office or rank in a formal organizational system. It is the influence capacity a leader derives from having higher status than the followers have. Vice presidents and department heads have more power than staff personnel do because of the positions they hold in the organization. Position power includes legitimate, reward, coercive, and information power (Table 1.2).

Personal power is the influence capacity a leader derives from being seen by followers as likable and knowledgeable. When leaders act in ways that are important to followers, it gives leaders power. For example, some managers have power because their followers consider them to be good role models. Others have power because their followers view them as highly competent or considerate. In both cases, these managers’ power is ascribed to them by others, based on how they are seen in their relationships with others. Personal power includes referent and expert power (Table 1.2).

In discussions of leadership, it is not unusual for leaders to be described as wielders of power, as individuals who dominate others. In these instances, power is conceptualized as a tool that leaders use to achieve their own ends. Contrary to this view of power, Burns (1978) emphasized power from a relationship standpoint. For Burns, power is not an entity that leaders use over others to achieve their own ends; instead, power occurs in relationships. It should be used by leaders and followers to promote their collective goals.

In this text, our discussions of leadership treat power as a relational concern for both leaders and followers. We pay attention to how leaders work with followers to reach common goals.

Leadership and Coercion

Coercive power is one of the specific kinds of power available to leaders. Coercion involves the use of force to effect change. To coerce means to influ- ence others to do something against their will and may include manipulating penalties and rewards in their work environment. Coercion often involves the use of threats, punishment, and negative reward schedules. Classic examples of coercive leaders are Adolf Hitler in Germany, the Taliban leaders in Afghanistan, Jim Jones in Guyana, and North Korea’s Supreme Leader Kim Jong-il, each of whom has used power and restraint to force followers to engage in extreme behaviors.

It is important to distinguish between coercion and leadership because it allows us to separate out from our examples of leadership the behaviors of individuals such as Hitler, the Taliban, and Jones. In our discussions of leadership, coercive people are not used as models of ideal leadership. Our definition suggests that leadership is reserved for those who influence a group of individuals toward a common goal. Leaders who use coercion are interested in their own goals and seldom are interested in the wants and needs of followers. Using coercion runs counter to working with followers to achieve a common goal.

Leadership and Management

Leadership is a process that is similar to management in many ways. Leader- ship involves influence, as does management. Leadership entails working with people, which management entails as well. Leadership is concerned with effective goal accomplishment, and so is management. In general, many of the functions of management are activities that are consistent with the definition of leadership we set forth at the beginning of this chapter.

But leadership is also different from management. Whereas the study of leadership can be traced back to Aristotle, management emerged around the turn of the 20th century with the advent of our industrialized society. Man- agement was created as a way to reduce chaos in organizations, to make them run more effectively and efficiently. The primary functions of manage- ment, as first identified by Fayol (1916), were planning, organizing, staffing, and controlling. These functions are still representative of the field of man- agement today.

In a book that compared the functions of management with the functions of leadership, Kotter (1990) argued that the functions of the two are quite dis- similar (Figure 1.2). The overriding function of management is to provide order and consistency to organizations, whereas the primary function of leadership is to produce change and movement. Management is about seek- ing order and stability; leadership is about seeking adaptive and constructive change.

As illustrated in Figure 1.2, the major activities of management are played out differently than the activities of leadership. Although they are different in scope, Kotter (1990, pp. 7–8) contended that both management and lead- ership are essential if an organization is to prosper. For example, if an orga- nization has strong management without leadership, the outcome can be stifling and bureaucratic. Conversely, if an organization has strong leadership without management, the outcome can be meaningless or misdirected change for change’s sake. To be effective, organizations need to nourish both competent management and skilled leadership.

figure 1.2 Functions of Management and Leadership

Management produces Order and Consistency

Planning and Budgeting

· Establish agendas

· Set timetables

· Allocate resources Organizing and Staffing

· Provide structure

· Make job placements

· Establish rules and procedures

Controlling and Problem Solving

· Develop incentives

· Generate creative solutions

· Take corrective action

Leadership produces Change and Movement

Establishing Direction

· Create a vision

· Clarify big picture

· Set strategies Aligning People

· Communicate goals

· Seek commitment

· Build teams and coalitions

Motivating and Inspiring

· Inspire and energize

· Empower followers

· Satisfy unmet needs

souRce: adapted from A Force for Change: How Leadership Differs From Management

(pp. 3–8), by J. p. Kotter, 1990, new york: Free press.

Many scholars, in addition to Kotter (1990), argue that leadership and management are distinct constructs. For example, Bennis and Nanus (1985) maintained that there is a significant difference between the two. To manage means to accomplish activities and master routines, whereas to lead means to influence others and create visions for change. Bennis and Nanus made the distinction very clear in their frequently quoted sentence, “Managers are people who do things right and leaders are people who do the right thing” (p. 221).

Rost (1991) has also been a proponent of distinguishing between leadership and management. He contended that leadership is a multidirectional influence relationship and management is a unidirectional authority relationship. Whereas leadership is concerned with the process of developing mutual purposes, management is directed toward coordinating activities in order to get a job done. Leaders and followers work together to create real change, whereas managers and subordinates join forces to sell goods and services (Rost, 1991, pp. 149–152).

In a recent study, Simonet and Tett (2012) explored how leadership and management are best conceptualized by having 43 experts identify the overlap and differences between leadership and management in regard to 63 different competencies. They found a large number of competencies (22)

descriptive of both leadership and management (e.g., productivity, customer focus, professionalism, and goal setting), but they also found several unique descriptors for each. Specifically, they found leadership was distinguished by motivating intrinsically, creative thinking, strategic planning, tolerance of ambiguity, and being able to read people, and management was distinguished by rule orientation, short-term planning, motivating extrinsically, orderli- ness, safety concerns, and timeliness.

Approaching the issue from a narrower viewpoint, Zaleznik (1977) went so far as to argue that leaders and managers themselves are distinct, and that they are basically different types of people. He contended that managers are reactive and prefer to work with people to solve problems but do so with low emotional involvement. They act to limit choices. Zaleznik suggested that leaders, on the other hand, are emotionally active and involved. They seek to shape ideas instead of responding to them and act to expand the available options to solve long-standing problems. Leaders change the way people think about what is possible.

Although there are clear differences between management and leadership, the two constructs overlap. When managers are involved in influencing a group to meet its goals, they are involved in leadership. When leaders are involved in planning, organizing, staffing, and controlling, they are involved in management. Both processes involve influencing a group of individuals toward goal attainment. For purposes of our discussion in this book, we focus on the leadership process. In our examples and case studies, we treat the roles of managers and leaders similarly and do not emphasize the differ- ences between them.

Plan of the Book

This book is user-friendly. It is based on substantive theories but is written to emphasize practice and application. Each chapter in the book follows the same format. The first section of each chapter briefly describes the leader- ship approach and discusses various research studies applicable to the approach. The second section of each chapter evaluates the approach, high- lighting its strengths and criticisms. Special attention is given to how the approach contributes or fails to contribute to an overall understanding of the leadership process. The next section uses case studies to prompt discus- sion of how the approach can be applied in ongoing organizations. Finally, each chapter provides a leadership questionnaire along with a discussion of how the questionnaire measures the reader’s leadership style. Each chapter ends with a summary and references.

Summary

Leadership is a topic with universal appeal; in the popular press and aca- demic research literature, much has been written about leadership. Despite the abundance of writing on the topic, leadership has presented a major challenge to practitioners and researchers interested in understanding the nature of leadership. It is a highly valued phenomenon that is very complex.

Through the years, leadership has been defined and conceptualized in many ways. The component common to nearly all classifications is that leadership is an influence process that assists groups of individuals toward goal attain- ment. Specifically, in this book leadership is defined as a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal.

Because both leaders and followers are part of the leadership process, it is important to address issues that confront followers as well as issues that confront leaders. Leaders and followers should be understood in relation to each other.

In prior research, many studies have focused on leadership as a trait. The trait perspective suggests that certain people in our society have special inborn qualities that make them leaders. This view restricts leadership to those who are believed to have special characteristics. In contrast, the approach in this text suggests that leadership is a process that can be learned, and that it is available to everyone.

Two common forms of leadership are assigned and emergent. Assigned leader- ship is based on a formal title or position in an organization. Emergent lead- ership results from what one does and how one acquires support from fol- lowers. Leadership, as a process, applies to individuals in both assigned roles and emergent roles.

Related to leadership is the concept of power, the potential to influence. There are two major kinds of power: position and personal. Position power, which is much like assigned leadership, is the power an individual derives from having a title in a formal organizational system. It includes legitimate, reward, infor- mation, and coercive power. Personal power comes from followers and includes referent and expert power. Followers give it to leaders because followers believe leaders have something of value. Treating power as a shared resource is impor- tant because it deemphasizes the idea that leaders are power wielders.

While coercion has been a common power brought to bear by many indi- viduals in charge, it should not be viewed as ideal leadership. Our definition of leadership stresses using influence to bring individuals toward a common goal, while coercion involves the use of threats and punishment to induce change in followers for the sake of the leaders. Coercion runs counter to leadership because it does not treat leadership as a process that emphasizes working with followers to achieve shared objectives.

Leadership and management are different concepts that overlap. They are different in that management traditionally focuses on the activities of plan- ning, organizing, staffing, and controlling, whereas leadership emphasizes the general influence process. According to some researchers, management is concerned with creating order and stability, whereas leadership is about adaptation and constructive change. Other researchers go so far as to argue that managers and leaders are different types of people, with managers being more reactive and less emotionally involved and leaders being more proactive and more emotionally involved. The overlap between leadership and man- agement is centered on how both involve influencing a group of individuals in goal attainment.

In this book, we discuss leadership as a complex process. Based on the research literature, we describe selected approaches to leadership and assess how they can be used to improve leadership in real situations.

Trait Approach

Description

Of interest to scholars throughout the 20th century, the trait approach was one of the first systematic attempts to study leadership. In the early 20th century, leadership traits were studied to determine what made certain people great leaders. The theories that were developed were called “great man” theories because they focused on identifying the innate qualities and characteristics possessed by great social, political, and military leaders (e.g., Catherine the Great, Mohandas Gandhi, Indira Gandhi, Abraham Lincoln, Joan of Arc, and Napoleon Bonaparte). It was believed that people were born with these traits, and that only the “great” people possessed them. During this time, research concentrated on determining the specific traits that clearly differentiated leaders from followers (Bass, 1990; Jago, 1982).

In the mid-20th century, the trait approach was challenged by research that questioned the universality of leadership traits. In a major review, Stogdill (1948) suggested that no consistent set of traits differentiated leaders from nonleaders across a variety of situations. An individual with leadership traits who was a leader in one situation might not be a leader in another situation. Rather than being a quality that individuals possess, leadership was reconceptualized as a relationship between people in a social situation. Personal factors related to leadership continued to be important, but researchers contended that these factors were to be considered as relative to the requirements of the situation.

The trait approach has generated much interest among researchers for its explanation of how traits influence leadership (Bryman, 1992). For example, an analysis of much of the previous trait research by Lord, DeVader, andAlliger (1986) found that traits were strongly associated with individuals’ perceptions of leadership. Similarly, Kirkpatrick and Locke (1991) went so far as to claim that effective leaders are actually distinct types of people in several key respects.

The trait approach has earned new interest through the current emphasis given by many researchers to visionary and charismatic leadership (see Bass, 1990; Bennis & Nanus, 1985; Nadler & Tushman, 1989; Zaccaro, 2007; Zaleznik, 1977). Charismatic leadership catapulted to the forefront of public attention with the 2008 election of the United States’ first African American president, Barack Obama, who is perceived by many to be charismatic, among many other attributes. In a study to determine what distinguishes charismatic leaders from others, Jung and Sosik (2006) found that charismatic leaders consistently possess traits of self-monitoring, engagement in impression management, motivation to attain social power, and motivation to attain self-actualization. In short, the trait approach is alive and well. It began with an emphasis on identifying the qualities of great persons, shifted to include the impact of situations on leadership, and, currently, has shifted back to reemphasize the critical role of traits in effective leadership.

Although the research on traits spanned the entire 20th century, a good overview of this approach is found in two surveys completed by Stogdill (1948, 1974). In his first survey, Stogdill analyzed and synthesized more than 124 trait studies conducted between 1904 and 1947. In his second study, he analyzed another 163 studies completed between 1948 and 1970. By taking a closer look at each of these reviews, we can obtain a clearer picture of how individuals’ traits contribute to the leadership process.

Stogdill’s first survey identified a group of important leadership traits that were related to how individuals in various groups became leaders. His results showed that the average individual in the leadership role is different from an average group member with regard to the following eight traits: intelligence, alertness, insight, responsibility, initiative, persistence, self-confidence, and sociability.

The findings of Stogdill’s first survey also indicated that an individual does not become a leader solely because that individual possesses certain traits. Rather, the traits that leaders possess must be relevant to situations in which the leader is functioning. As stated earlier, leaders in one situation may not necessarily be leaders in another situation. Findings showed that leadership was not a passive state but resulted from a working relationship between the leader and other group members. This research marked the beginning of a new approach to leadership research that focused on leadership behaviors and leadership situations.

Stogdill’s second survey, published in 1974, analyzed 163 new studies and compared the findings of these studies to the findings he had reported in his first survey. The second survey was more balanced in its description of the role of traits and leadership. Whereas the first survey implied that leadership is determined principally by situational factors and not traits, the second survey argued more moderately that both traits and situational factors were determinants of leadership. In essence, the second survey validated the original trait idea that a leader’s characteristics are indeed a part of leadership.

Similar to the first survey, Stogdill’s second survey also identified traits that were positively associated with leadership. The list included the following 10 characteristics:

1. drive for responsibility and task completion;

2. vigor and persistence in pursuit of goals;

3. risk taking and originality in problem solving;

4. drive to exercise initiative in social situations;

5. self-confidence and sense of personal identity;

6. willingness to accept consequences of decision and action;

7. readiness to absorb interpersonal stress;

8. willingness to tolerate frustration and delay;

9. ability to influence other people’s behavior; and

10. capacity to structure social interaction systems to the purpose at hand.

Mann (1959) conducted a similar study that examined more than 1,400 findings regarding traits and leadership in small groups, but he placed less emphasis on how situational factors influenced leadership. Although tentative in his conclusions, Mann suggested that certain traits could be used to distinguish leaders from nonleaders. His results identified leaders as strong in the following six traits: intelligence, masculinity, adjustment, dominance, extraversion, and conservatism.

Lord et al. (1986) reassessed Mann’s (1959) findings using a more sophisticated procedure called meta-analysis. Lord et al. found that intelligence, masculinity, and dominance were significantly related to how individuals perceived leaders. From their findings, the authors argued strongly that traits could be used to make discriminations consistently across situations between leaders and nonleaders.

Both of these studies were conducted during periods in American history where male leadership was prevalent in most aspects of business and society. In Chapter 15, we explore more contemporary research regarding the role of gender in leadership, and we look at whether traits such as masculinity and dominance still bear out as important factors in distinguishing between leaders and nonleaders.

Yet another review argues for the importance of leadership traits: Kirkpatrick and Locke (1991, p. 59) contended that “it is unequivocally clear that leaders are not like other people.” From a qualitative synthesis of earlier research, Kirkpatrick and Locke postulated that leaders differ from nonleaders on six traits: drive, motivation, integrity, confidence, cognitive ability, and task knowledge. According to these writers, individuals can be born with these traits, they can learn them, or both. It is these six traits that make up the

“right stuff ” for leaders. Kirkpatrick and Locke contended that leadership traits make some people different from others, and this difference should be recognized as an important part of the leadership process.

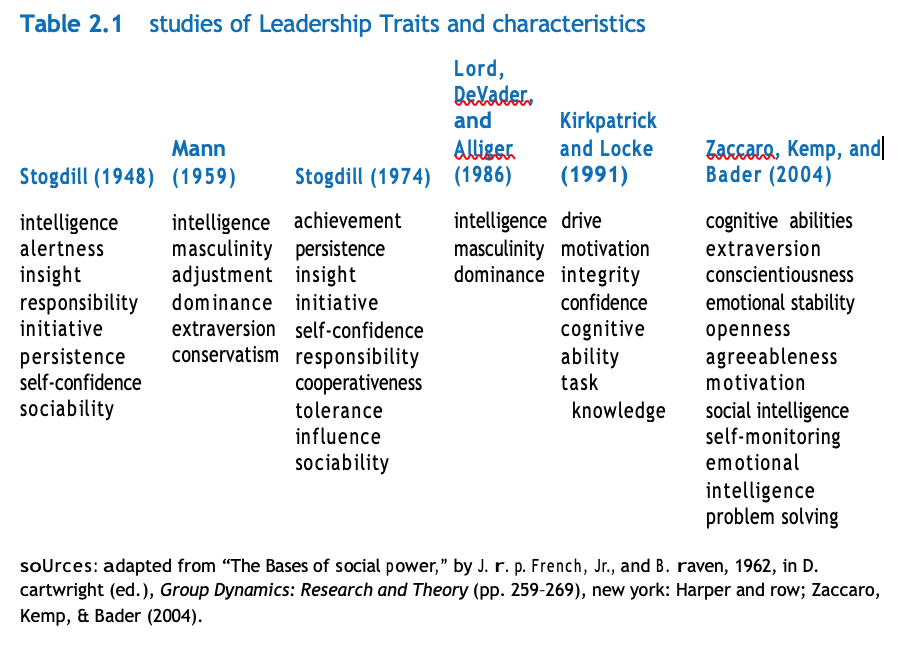

In the 1990s, researchers began to investigate the leadership traits associated with “social intelligence,” characterized as those abilities to understand one’s own and others’ feelings, behaviors, and thoughts and to act appropriately (Marlowe, 1986). Zaccaro (2002) defined social intelligence as having such capacities as social awareness, social acumen, self-monitoring, and the ability to select and enact the best response given the contingencies of the situation and social environment. A number of empirical studies showed these capacities to be a key trait for effective leaders. Zaccaro, Kemp, and Bader (2004) included such social abilities in the categories of leadership traits they outlined as important leadership attributes (see Table 2.1).

Table 2.1 provides a summary of the traits and characteristics that were identified by researchers from the trait approach. It illustrates clearly the breadth of traits related to leadership. Table 2.1 also shows how difficult it is to select certain traits as definitive leadership traits; some of the traits appear in several of the survey studies, whereas others appear in only one or two studies. Regardless of the lack of precision in Table 2.1, however, it represents a general convergence of research regarding which traits are leadership traits.

What, then, can be said about trait research? What has a century of research on the trait approach given us that is useful? The answer is an extended list of traits that individuals might hope to possess or wish to cultivate if they want to be perceived by others as leaders. Some of the traits that are central to this list include intelligence, self-confidence, determination, integrity, and sociability (Table 2.2).

Intelligence

Intelligence or intellectual ability is positively related to leadership. Based on their analysis of a series of recent studies on intelligence and various indices of leadership, Zaccaro et al. (2004) found support for the finding that leaders tend to have higher intelligence than nonleaders. Having strong verbal

ability, perceptual ability, and reasoning appears to make one a better leader. Although it is good to be bright, the research also indicates that a leader’s intellectual ability should not differ too much from that of the subordinates. If the leader’s IQ is very different from that of the followers, it can have a counterproductive impact on leadership. Leaders with higher abilities may have difficulty communicating with followers because they are preoccupied or because their ideas are too advanced for their followers to accept.

An example of a leader for whom intelligence was a key trait was Steve Jobs, founder and CEO of Apple who died in 2011. Jobs once said, “I have this really incredible product inside me and I have to get it out” (Sculley, 2011,

p. 27). Those visionary products, first the Apple II and Macintosh computers and then the iMac, iPod, iPhone, and iPad, have revolutionized the personal computer and electronic device industry, changing the way people play and work.

In the next chapter of this text, which addresses leadership from a skills perspective, intelligence is identified as a trait that significantly contributes to a leader’s acquisition of complex problem-solving skills and social judgment skills. Intelligence is described as having a positive impact on an individual’s capacity for effective leadership.

Self-confidence is another trait that helps one to be a leader. Self-confidence is the ability to be certain about one’s competencies and skills. It includes a sense of self-esteem and self-assurance and the belief that one can make a difference. Leadership involves influencing others, and self-confidence allows the leader to feel assured that his or her attempts to influence others are appropriate and right.

Again, Steve Jobs is a good example of a self-confident leader. When Jobs described the devices he wanted to create, many people said they weren’t possible. But Jobs never doubted his products would change the world, and, despite resistance, he did things the way he thought best. “Jobs was one of those CEOs who ran the company like he wanted to. He believed he knew more about it than anyone else, and he probably did,” said a colleague (Stone, 2011).

Many leaders also exhibit determination. Determination is the desire to get the job done and includes characteristics such as initiative, persistence, dominance, and drive. People with determination are willing to assert themselves, are proactive, and have the capacity to persevere in the face of obstacles. Being determined includes showing dominance at times and in situations where followers need to be directed.

Dr. Paul Farmer has shown determination in his efforts to secure health care and eradicate tuberculosis for the very poor of Haiti and other third world countries. He began his efforts as a recent college graduate, traveling and working in Cange, Haiti. While there, he was accepted to Harvard Medical School. Knowing that his work in Haiti was invaluable to his training, he managed to do both: spending months traveling back and forth between Haiti and Cambridge, Massachusetts, for school. His first effort in Cange was to establish a one-room clinic where he treated “all comers” and trained local health care workers. Farmer found that there was more to providing health care than just dispensing medicine: He secured donations to build schools, houses, and communal sanitation and water facilities in the region. He spearheaded vaccinations of all the children in the area, dramatically reducing malnutrition and infant mortality. In order to keep working in Haiti, he returned to America and founded Partners In Health, a charitable foundation that raises money to fund these efforts. Since its founding, PIH not only has succeeded in improving the health of many communities in Haiti but now has projects in Haiti, Lesotho, Malawi, Peru, Russia, Rwanda, and the United States, and supports other projects in Mexico and Guatemala (Kidder, 2004; Partners In Health, 2014).

Integrity is another of the important leadership traits. Integrity is the quality of honesty and trustworthiness. People who adhere to a strong set of principles and take responsibility for their actions are exhibiting integrity. Leaders with integrity inspire confidence in others because they can be trusted to do what they say they are going to do. They are loyal, dependable, and not deceptive. Basically, integrity makes a leader believable and worthy of our trust.

In our society, integrity has received a great deal of attention in recent years. For example, as a result of two situations—the position taken by President George W. Bush regarding Iraq’s alleged weapons of mass destruction and the impeachment proceedings during the Clinton presidency—people are demanding more honesty of their public officials. Similarly, scandals in the corporate world (e.g., Enron and WorldCom) have led people to become skeptical of leaders who are not highly ethical. In the educational arena, new

K–12 curricula are being developed to teach character, values, and ethical leadership. (For instance, see the Character Counts! program developed by the Josephson Institute of Ethics in California at www.charactercounts.org, and the Pillars of Leadership program taught at the J. W. Fanning Institute for Leadership in Georgia at www.fanning.uga.edu.) In short, society is demanding greater integrity of character in its leaders.

A final trait that is important for leaders is sociability. Sociability is a leader’s inclination to seek out pleasant social relationships. Leaders who show sociability are friendly, outgoing, courteous, tactful, and diplomatic. They are sensitive to others’ needs and show concern for their well-being. Social leaders have good interpersonal skills and create cooperative relationships with their followers.

An example of a leader with great sociability skills is Michael Hughes, a university president. Hughes prefers to walk to all his meetings because it gets him out on campus where he greets students, staff, and faculty. He has lunch in the dorm cafeterias or student union and will often ask a table of strangers if he can sit with them. Students rate him as very approachable, while faculty say he has an open-door policy. In addition, he takes time to write personal notes to faculty, staff, and students to congratulate them on their successes.

Although our discussion of leadership traits has focused on five major traits (i.e., intelligence, self-confidence, determination, integrity, and sociability), this list is not all-inclusive. While other traits indicated in Table 2.1 are associated with effective leadership, the five traits we have identified contribute substantially to one’s capacity to be a leader.

Until recently, most reviews of leadership traits have been qualitative. In addition, they have lacked a common organizing framework. However, the research described in the following section provides a quantitative assessment of leadership traits that is conceptually framed around the five-factor model of personality. It describes how five major personality traits are related to leadership.

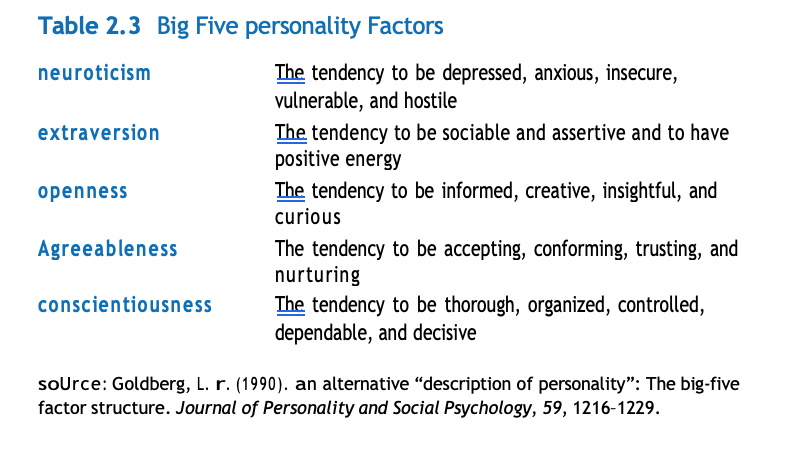

Five-Factor Personality Model and Leadership

Over the past 25 years, a consensus has emerged among researchers regarding the basic factors that make up what we call personality (Goldberg, 1990;

McCrae & Costa, 1987). These factors, commonly called the Big Five, are neuroticism, extraversion (surgency), openness (intellect), agreeableness, and conscientiousness (dependability). (See Table 2.3.)

To assess the links between the Big Five and leadership, Judge, Bono, Ilies, and Gerhardt (2002) conducted a major meta-analysis of 78 leadership and personality studies published between 1967 and 1998. In general, Judge et al. found a strong relationship between the Big Five traits and leadership. It appears that having certain personality traits is associated with being an effective leader.

Specifically, in their study, extraversion was the factor most strongly associated with leadership. It is the most important trait of effective leaders. Extraversion was followed, in order, by conscientiousness, openness, and low neuroticism. The last factor, agreeableness, was found to be only weakly associated with leadership.

Emotional Intelligence

Another way of assessing the impact of traits on leadership is through the concept of emotional intelligence, which emerged in the 1990s as an important area of study in psychology. It has been widely studied by researchers, and has captured the attention of many practitioners (Caruso & Wolfe, 2004; Goleman, 1995, 1998; Mayer & Salovey, 1995, 1997; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000; Shankman & Allen, 2008).

As the two words suggest, emotional intelligence has to do with our emotions (affective domain) and thinking (cognitive domain), and the interplay between the two. Whereas intelligence is concerned with our ability to learn information and apply it to life tasks, emotional intelligence is concerned with our ability to understand emotions and apply this understanding to life’s tasks. Specifically, emotional intelligence can be defined as the ability to perceive and express emotions, to use emotions to facilitate thinking, to understand and reason with emotions, and to effectively manage emotions within oneself and in relationships with others (Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2000).

There are different ways to measure emotional intelligence. One scale is the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test (MSCEIT; Mayer, Caruso, & Salovey, 2000). The MSCEIT measures emotional intelligence as a set of mental abilities, including the abilities to perceive, facilitate, understand, and manage emotion.

Goleman (1995, 1998) takes a broader approach to emotional intelligence, suggesting that it consists of a set of personal and social competencies. Personal competence consists of self-awareness, confidence, self-regulation, conscientiousness, and motivation. Social competence consists of empathy and social skills such as communication and conflict management.

Shankman and Allen (2008) developed a practice-oriented model of emotionally intelligent leadership, which suggests that leaders must be conscious of three fundamental facets of leadership: context, self, and others. In the model, emotionally intelligent leaders are defined by 21 capacities to which a leader should pay attention, including group savvy, optimism, initiative, and teamwork.

There is a debate in the field regarding how big a role emotional intelligence plays in helping people be successful in life. Some researchers, such as Goleman (1995), suggested that emotional intelligence plays a major role in whether people are successful at school, home, and work. Others, such as Mayer, Salovey, and Caruso (2000), made softer claims for the significance of emotional intelligence in meeting life’s challenges.

As a leadership ability or trait, emotional intelligence appears to be an important construct. The underlying premise suggested by this framework is that people who are more sensitive to their emotions and the impact of their emotions on others will be leaders who are more effective. As more research is conducted on emotional intelligence, the intricacies of how emotional intelligence relates to leadership will be better understood.

How Does The Trait Approach Work?

The trait approach is very different from the other approaches discussed in subsequent chapters because it focuses exclusively on the leader, not on the followers or the situation. This makes the trait approach theoretically more straightforward than other approaches. In essence, the trait approach is concerned with what traits leaders exhibit and who has these traits.

The trait approach does not lay out a set of hypotheses or principles about what kind of leader is needed in a certain situation or what a leader should do, given a particular set of circumstances. Instead, this approach emphasizes that having a leader with a certain set of traits is crucial to having effective leadership. It is the leader and the leader’s traits that are central to the leadership process.

The trait approach suggests that organizations will work better if the people in managerial positions have designated leadership profiles. To find the right people, it is common for organizations to use trait assessment instruments. The assumption behind these procedures is that selecting the right people will increase organizational effectiveness. Organizations can specify the characteristics or traits that are important to them for particular positions and then use trait assessment measures to determine whether an individual fits their needs.

The trait approach is also used for personal awareness and development. By analyzing their own traits, managers can gain an idea of their strengths and weaknesses, and can get a feel for how others in the organization see them. A trait assessment can help managers determine whether they have the qualities to move up or to move to other positions in the company.

A trait assessment gives individuals a clearer picture of who they are as leaders and how they fit into the organizational hierarchy. In areas where their traits are lacking, leaders can try to make changes in what they do or where they work to increase their traits’ potential impact.

Near the end of the chapter, a leadership instrument is provided that you can use to assess your leadership traits. This instrument is typical of the kind of assessments that companies use to evaluate individuals’ leadership potential. As you will discover by completing this instrument, trait measures are a good way to assess your own characteristics.

Strengths

The trait approach has several identifiable strengths. First, the trait approach is intuitively appealing. It fits clearly with our notion that leaders are the individuals who are out front and leading the way in our society. The image in the popular press and community at large is that leaders are a special kind of people—people with gifts who can do extraordinary things. The trait approach is consistent with this perception because it is built on the premise that leaders are different, and their difference resides in the special traits they possess. People have a need to see their leaders as gifted people, and the trait approach fulfills this need.

A second strength of the trait approach is that it has a century of research to back it up. No other theory can boast of the breadth and depth of studies conducted on the trait approach. The strength and longevity of this line of research give the trait approach a measure of credibility that other approaches lack. Out of this abundance of research has emerged a body of data that points to the important role of various traits in the leadership process.

Another strength, more conceptual in nature, results from the way the trait approach highlights the leader component in the leadership process. Leadership is composed of leaders, followers, and situations, but the trait approach is devoted to only the first of these—leaders. Although this is also a potential weakness, by focusing exclusively on the role of the leader in leadership the trait approach has been able to provide us with a deeper and more intricate understanding of how the leader and the leader’s traits are related to the leadership process.

Last, the trait approach has given us some benchmarks for what we need to look for if we want to be leaders. It identifies what traits we should have and whether the traits we do have are the best traits for leadership. Based on the findings of this approach, trait assessment procedures can be used to offer invaluable information to supervisors and managers about their strengths and weaknesses and ways to improve their overall leadership effectiveness.

Criticisms

In addition to its strengths, the trait approach has several weaknesses. First and foremost is the failure of the trait approach to delimit a definitive list of leadership traits. Although an enormous number of studies have been conducted over the past 100 years, the findings from these studies have

been ambiguous and uncertain at times. Furthermore, the list of traits that has emerged appears endless. This is obvious from Table 2.1, which lists a multitude of traits. In fact, these are only a sample of the many leadership traits that were studied.

Another criticism is that the trait approach has failed to take situations into account. As Stogdill (1948) pointed out more than 60 years ago, it is difficult to isolate a set of traits that are characteristic of leaders without also factoring situational effects into the equation. People who possess certain traits that make them leaders in one situation may not be leaders in another situation. Some people may have the traits that help them emerge as leaders but not the traits that allow them to maintain their leadership over time. In other words, the situation influences leadership. It is therefore difficult to identify a universal set of leadership traits in isolation from the context in which the leadership occurs.

A third criticism, derived from the prior two criticisms, is that this approach has resulted in highly subjective determinations of the most important leadership traits. Because the findings on traits have been so extensive and broad, there has been much subjective interpretation of the meaning of the data. This subjectivity is readily apparent in the many self-help, practice- oriented management books. For example, one author might identify ambition and creativity as crucial leadership traits; another might identify empathy and calmness. In both cases, it is the author’s subjective experience and observations that are the basis for the identified leadership traits. These books may be helpful to readers because they identify and describe important leadership traits, but the methods used to generate these lists of traits are weak. To respond to people’s need for a set of definitive traits of leaders, authors have set forth lists of traits, even if the origins of these lists are not grounded in strong, reliable research.

Research on traits can also be criticized for failing to look at traits in relationship to leadership outcomes. This research has emphasized the identification of traits, but has not addressed how leadership traits affect group members and their work. In trying to ascertain universal leadership traits, researchers have focused on the link between specific traits and leader emergence, but they have not tried to link leader traits with other outcomes such as productivity or employee satisfaction. For example, trait research does not provide data on whether leaders who might have high intelligence and strong integrity have better results than leaders without these traits. The trait approach is weak in describing how leaders’ traits affect the outcomes of groups and teams in organizational settings.

A final criticism of the trait approach is that it is not a useful approach for training and development for leadership. Even if definitive traits could be identified, teaching new traits is not an easy process because traits are not easily changed. For example, it is not reasonable to send managers to a training program to raise their IQ or to train them to become extraverted. The point is that traits are largely fixed psychological structures, and this limits the value of teaching and leadership training.

Application

Despite its shortcomings, the trait approach provides valuable information about leadership. It can be applied by individuals at all levels and in all types of organizations. Although the trait approach does not provide a definitive set of traits, it does provide direction regarding which traits are good to have if one aspires to a leadership position. By taking trait assessments and other similar questionnaires, people can gain insight into whether they have certain traits deemed important for leadership, and they can pinpoint their strengths and weaknesses with regard to leadership.

As we discussed previously, managers can use information from the trait approach to assess where they stand in their organization and what they need to do to strengthen their position. Trait information can suggest areas in which their personal characteristics are very beneficial to the company and areas in which they may want to get more training to enhance their overall approach. Using trait information, managers can develop a deeper understanding of who they are and how they will affect others in the organization.

Case Studies

In this section, three case studies (Cases 2.1, 2.2, and 2.3) are provided to illustrate the trait approach and to help you understand how the trait approach can be used in making decisions in organizational settings. The settings of the cases are diverse—directing research and development at a large snack food company, running an office supply business, and being head of recruitment for a large bank—but all of the cases deal with trait leadership. At the end of each case, you will find questions that will help in analyzing the cases.

Case 2. 1Choosing a New Director of Research

sandra coke is vice president for research and development at Great Lakes Foods (GLF), a large snack food company that has approximately 1,000 employees. as a result of a recent reorganization, sandra must choose the new director of research. The director will report directly to sandra and will be responsible for developing and testing new products. The research division of GLF employs about 200 people. The choice of directors is important because sandra is receiving pressure from the president and board of GLF to improve the company’s overall growth and productivity.

sandra has identified three candidates for the position. each candidate is at the same managerial level. she is having difficulty choosing one of them because each has very strong credentials. alexa smith is a longtime employee of GLF who started part-time in the mailroom while in high school. after finishing school, alexa worked in as many as 10 different positions throughout the company to become manager of new product marketing. performance reviews of alexa’s work have repeatedly described her as being very creative and insightful. in her tenure at GLF, alexa has developed and brought to market four new product lines. alexa is also known throughout GLF as being very persistent about her work: When she starts a project, she stays with it until it is finished. it is probably this quality that accounts for the success of each of the four new products with which she has been involved.

a second candidate for the new position is Kelsey Metts, who has been with GLF for 5 years and is manager of quality control for established products. Kelsey has a reputation for being very bright. Before joining GLF, she received her MBa at Harvard, graduating at the top of her class. people talk about Kelsey as the kind of person who will be president of her own company someday. Kelsey is also very personable. on all her performance reviews, she received extra-high scores on sociability and human relations. There isn’t a supervisor in the company who doesn’t have positive things to say about how comfortable it is to work with Kelsey. since joining GLF, Kelsey has been instrumental in bringing two new product lines to market.

Thomas santiago, the third candidate, has been with GLF for 10 years and is often consulted by upper management regarding strategic plan- ning and corporate direction setting. Thomas has been very involved in establishing the vision for GLF and is a company person all the way. He believes in the values of GLF, and actively promotes its mission. The two qualities that stand out above the rest in Thomas's performance reviews are his honesty and integrity. Employees who have worked under his supervision consistently report that they feel they can trust Thomas to be fair and consistent. Thomas has been involved in some capacity with the development of three new product lines. The challenge confronting Sandra is to choose the best person for the newly established director's position. Because of the pressure she feels from upper management, Sandra knows she must select the best leader for the new position.

Questions

1. Based on the information provided about the trait approach in Tables 2.1 and 2.2, if you were Sandra, whom would you select?

2. In what ways is the trait approach helpful in this type of selection?

3. In what ways are the weaknesses of the trait approach highlighted in this case?

Case 2.2

Carol Baines was married for 20 years to the owner of the Baines company until he died in a car accident. After his death, Carol decided not to sell the business but to try to run it herself. Before the accident, her only involvement in the business was in informal discussions with her husband over dinner, although she has a college degree in business, with a major in management.

Baines company was one of th three office supply stores in a city with a population of 200,000 people. The other two stores were owned by national chains. Baines was not a large company, and employed only five people. Baines had stable sales of about $200,000 a year, serving mostly the smaller companies in the city. The firm had not grown in a number of years and was beginning to feel the pressure of the advertising and lower prices of the national chains. For the first 6 months, carol spent her time familiarizing herself with the employees and the operations of the company. Next, she did a citywide

analysis of companies that had reason to purchase office supplies. Based on her understanding of the company’s capabilities and her assessment of the potential market for their products and services, carol developed a specific set of short-term and long-term goals for the company. Behind all of her planning, carol had a vision that Baines could be a viable, healthy, and competitive company. she wanted to carry on the business that her husband had started, but more than that she wanted it to grow. over the first 5 years, carol invested significant amounts of money in advertising, sales, and services. These efforts were well spent because the company began to show rapid growth immediately. Because of the growth, the company hired another 20 people. The expansion at Baines was particularly remarkable because of another major hardship carol had to confront. carol was diagnosed with breast cancer a year after her husband died. The treatment for her cancer included 2 months of radiation therapy and 6 months of strong chemo- therapy. although the side effects included hair loss and fatigue, carol continued to manage the company throughout the ordeal. Despite her difficulties, carol was successful. Under the strength of her leadership, the growth at Baines continued for 10 consecutive years. interviews with new and old employees at Baines revealed much about carol’s leadership. employees said that carol was a very solid person. she cared deeply about others and was fair and considerate. They said she created a family-like atmosphere at Baines. Few employees had quit Baines since carol took over. carol was devoted to all the employees, and she supported their interests. For example, the company sponsored a softball team in the summer and a basketball team in the winter. others described carol as a strong person. even though she had cancer, she continued to be positive and interested in them. she did not get depressed about the cancer and its side effects, even though coping with cancer was difficult. employees said she was a model of strength, good- ness, and quality. at age 55, carol turned the business over to her two sons. she continues to act as the president but does not supervise the day-to-day operations. The company is doing more than $3.1 million in sales, and it outpaces the two chain stores in the city.

Questions

1. How would you describe Carol's leadership traits?

2. How big a part did Carol's traits play in the expansion of the company?

3. Would Carol be a leader in other business contexts?

Case 2.3

Recruiting for theBank

pat nelson is the assistant director of human resources in charge of recruitment for central Bank, a large, full-service banking institu- tion. one of pat’s major responsibilities each spring is to visit as many college campuses as he can to interview graduating seniors for credit analyst positions in the commercial lending area at central Bank. although the number varies, he usually ends up hiring about 20 new people, most of whom come from the same schools, year after year.

pat has been doing recruitment for the bank for more than 10 years, and he enjoys it very much. However, for the upcoming spring he is feeling increased pressure from management to be particularly dis- criminating about whom he recommends hiring. Management is con- cerned about the retention rate at the bank because in recent years as many as 25% of the new hires have left. Departures after the first year have meant lost training dollars and strain on the staff who remain. although management understands that some new hires always leave, the executives are not comfortable with the present rate, and they have begun to question the recruitment and hiring procedures.

The bank wants to hire people who can be groomed for higher-level leadership positions. although certain competencies are required of entry-level credit analysts, the bank is equally interested in skills that will allow individuals to advance to upper management positions as their careers progress.

in the recruitment process, pat always looks for several characteristics. First, applicants need to have strong interpersonal skills, they need to be confident, and they need to show poise and initiative. next, because banking involves fiduciary responsibilities, applicants need to have proper ethics, including a strong sense of the importance of confidentiality. in addition, to do the work in the bank, they need to have strong analytical and technical skills, and experience in working with computers. Last, applicants need to exhibit a good work ethic, and they need to show commitment and a willingness to do their job even in difficult circumstances.

pat is fairly certain that he has been selecting the right people to be leaders at central Bank, yet upper management is telling him to reassess his hiring criteria. although he feels that he has been doing the right thing, he is starting to question himself and his recruitment practices.

1. Based on ideas described in the traits approach, do you think Pat is looking for the right characteristics in the people he hires?

2. Could it be that the retention problem raised by upper management is unrelated to Pat's recruitment criteria?

3. If you were Pat, would you change your approach to recruiting?

Leadership Instrument

Organizations use a wide variety of questionnaires to measure individuals’ traits. In many organizations, it is common practice to use standard trait measures such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory or the Myers-Briggs Type Indicatorâ. These measures provide valuable information to the individual and the organization about the individual’s unique attributes for leadership and where the individual could best serve the organization.