Textbook Reading: Northouse Chapter 6

Path–Goal Theory

Description

Path–goal theory is about how leaders motivate followers to accomplish designated goals. Drawing heavily from research on what motivates followers, path–goal theory first appeared in the leadership literature in the early 1970s in the works of Evans (1970), House (1971), House and Dessler (1974), and House and Mitchell (1974). The stated goal of this leadership theory is to enhance follower performance and follower satisfaction by focusing on follower motivation.

In contrast to the situational approach, which suggests that a leader must adapt to the development level of followers (see Chapter 5), path–goal theory emphasizes the relationship between the leader’s style and the characteristics of the followers and the organizational setting. For the leader, the imperative is to use a leadership style that best meets followers’ motivational needs. This is done by choosing behaviors that complement or supplement what is missing in the work setting. Leaders try to enhance followers’ goal attainment by providing information or rewards in the work environment (Indvik, 1986); leaders provide followers with the elements they think followers need to reach their goals.

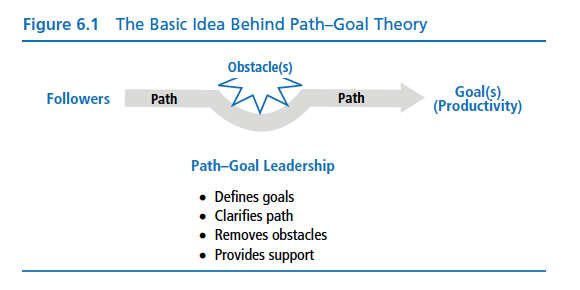

According to House and Mitchell (1974), leadership generates motivation when it increases the number and kinds of payoffs that followers receive from their work. Leadership also motivates when it makes the path to the goal clear and easy to travel through coaching and direction, removing obstacles and roadblocks to attaining the goal, and making the work itself more personally satisfying (Figure 6.1).

In brief, path–goal theory is designed to explain how leaders can help followers along the path to their goals by selecting specific behaviors that are best suited to followers’ needs and to the situation in which followers are working. By choosing the appropriate style, leaders increase followers’ expectations for success and satisfaction.

Within path-goal theory, motivation is conceptualized from the perspective of the expectancy theory of motivation (Vroom, 1964). The underlying assumption of expectancy theory is that followers will be motivated if they think they are capable of performing their work, if they believe their efforts will result in a certain outcome, and if they believe that the payoffs for doing their work are worthwhile. The challenge for a leader using ideas from expectancy theory is to understand fully the goals of each follower and the rewards associated with the goals. Followers want to feel efficacious like they can accomplish what they set out to do. But, they also want to know that they will be rewarded if they can accomplish their work. A leader needs to find out what is rewarding to followers about their work and then make those rewards available to them when they accomplish the requirements of their work. Expectancy theory is about the goals that followers choose and how leaders help them and reward them for meeting those goals.

Conceptually, path–goal theory is complex. It is useful to break it down into smaller units so we can better understand the complexities of this approach.

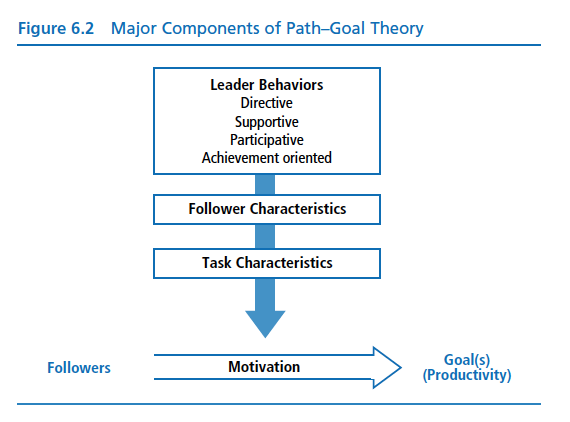

Figure 6.2 illustrates the different components of path–goal theory, including leader behaviors, follower characteristics, task characteristics, and motivation. Path–goal theory suggests that each type of leader behavior has a different kind of impact on followers’ motivation. Whether a particular leader behavior is motivating to followers is contingent on the followers’ characteristics and the characteristics of the task.

Leader Behaviors

Although many different leadership behaviors could have been selected to be a part of path–goal theory, this approach has so far examined directive, supportive, participative, and achievement-oriented leadership behaviors (House & Mitchell, 1974, p. 83). Path–goal theory is explicitly left open to the inclusion of other variables.

Directive Leadership

Directive leadership is similar to the “initiating structure” concept described in the Ohio State studies (Halpin & Winer, 1957) and the “telling” style described in Situational Leadershipâ. It characterizes a leader who gives followers instructions about their task, including what is expected of them, how it is to be done, and the timeline for when it should be completed. A directive leader sets clear standards of performance and makes the rules and regulations clear to followers.

supportive Leadership

Supportive leadership resembles the consideration behavior construct that was identified by the Ohio State studies discussed in Chapter 4. Supportive leadership consists of being friendly and approachable as a leader and

includes attending to the well-being and human needs of followers. Leaders using supportive behaviors go out of their way to make work pleasant for followers. In addition, supportive leaders treat followers as equals and give them respect for their status.

Participative Leadership

Participative leadership consists of inviting followers to share in the decision making. A participative leader consults with followers, obtains their ideas and opinions, and integrates their suggestions into the decisions about how the group or organization will proceed.

Achievement-oriented Leadership

Achievement-oriented leadership is characterized by a leader who challenges followers to perform work at the highest level possible. This leader establishes a high standard of excellence for followers and seeks continuous improvement. In addition to expecting a lot from followers, achievement- oriented leaders show a high degree of confidence that followers are capable of establishing and accomplishing challenging goals.

House and Mitchell (1974) suggested that leaders might exhibit any or all of these four styles with various followers and in different situations. Path–goal theory is not a trait approach that locks leaders into only one kind of leadership- ship. Leaders should adapt their styles to the situation or to the motivational needs of their followers. For example, if followers need participative leadership at one point in a task and directive leadership at another, the leader can change her or his style as needed. Different situations may call for different types of leadership behavior. Furthermore, there may be instances when it is appropriate for a leader to use more than one style at the same time.

In addition to leader behaviors, Figure 6.2 illustrates two other major components of path–goal theory: follower characteristics and task characteristics. Each of these two sets of characteristics influences the way leaders’ behaviors affect follower motivation. In other words, the impact of leadership is contingent on the characteristics of both followers and their task.

Follower Characteristics

Follower characteristics determine how a leader’s behavior is interpreted by followers in a given work context. Researchers have focused on followers’

needs for affiliation, preferences for structure, desires for control, and self-perceived level of task ability. These characteristics and many others determine the degree to which followers find the behavior of a leader an immediate source of satisfaction or instrumental to some future satisfaction.

Path–goal theory predicts that followers who have strong needs for affiliation prefer supportive leadership because friendly and concerned leadership is a source of satisfaction. For followers who are dogmatic and authoritarian and have to work in uncertain situations, path–goal theory suggests directive leadership because that provides psychological structure and task clarity. Directive leadership helps these followers by clarifying the path to the goal, making it less ambiguous. The authoritarian type of follower feels more comfortable when the leader provides a greater sense of certainty in the work setting.

Followers’ desires for control have received special attention in path–goal research through studies of a personality construct locus of control that can be subdivided into internal and external dimensions. Followers with an internal locus of control believe that they are in charge of the events that occur in their life, whereas those with an external locus of control believe that chance, fate, or outside forces determine life events. Path–goal theory suggests that for followers with an internal locus of control participative leadership is most satisfying because it allows them to feel in charge of their work and to be an integral part of decision making. For followers with an external locus of control, path–goal theory suggests that directive leadership is best because it parallels followers’ feelings that outside forces control their circumstances.

Another way in which leadership affects follower motivation is the followers’ perceptions of their own abilities to perform a specific task. As followers’ perceptions of their abilities and competence goes up, the need for directive leadership goes down. In effect, directive leadership becomes redundant and perhaps excessively controlling when followers feel competent to complete their own work.

Task Characteristics

In addition to follower characteristics, task characteristics also have a major impact on the way a leader’s behavior influences followers’ motivation (see Figure 6.2). Task characteristics include the design of the follower’s task, the formal authority system of the organization, and the primary work group of followers. Collectively, these characteristics in themselves can provide motivation for followers. When a situation provides a clearly structured task, strong group norms, and an established authority system, followers will find

the paths to desired goals apparent and will not need a leader to clarify goals or coach them in how to reach these goals. Followers will feel as if they can accomplish their work and that their work is of value. Leadership in these types of contexts could be seen as unnecessary, unempathic, and excessively controlling.

In some situations, however, the task characteristics may call for leadership involvement. Tasks that are unclear and ambiguous call for leadership input that provides structure. In addition, highly repetitive tasks call for leadership that gives support in order to maintain followers’ motivation. In work settings where the formal authority system is weak, leadership becomes a tool that helps followers by making the rules and work requirements clear. In contexts where the group norms are weak or nonsupportive, leadership assists in building cohesiveness and role responsibility.

A special focus of path–goal theory is helping followers overcome obstacles. Obstacles could be just about anything in the work setting that gets in the way of followers. Specifically, obstacles create excessive uncertainties, frustrations, or threats for followers. In these settings, path–goal theory suggests that it is the leader’s responsibility to help followers by removing these obstacles or helping them around them. Helping followers around these obstacles will increase followers’ expectations that they can complete the task and increase their sense of job satisfaction.

In 1996, House published a reformulated path–goal theory that extends his original work to include eight classes of leadership behaviors. Besides the four leadership behaviors discussed previously in this chapter—(a) directive,

(a) supportive, (c) participative, and (d) achievement-oriented behavior—the new theory adds (e) work facilitation, (f ) group-oriented decision process,

(g) work-group representation and networking, and (h) value-based leadership behavior. The essence of the new theory is the same as the original: To be effective, leaders need to help followers by giving them what is missing in their environment and by helping them compensate for deficiencies in their abilities.

How Does Path-Goal Theory work?

Path–goal theory is an approach to leadership that is not only theoretically complex, but also pragmatic. In theory, it provides a set of assumptions about how various leadership styles interact with characteristics of followers and the work setting to affect the motivation of followers. In practice, the theory

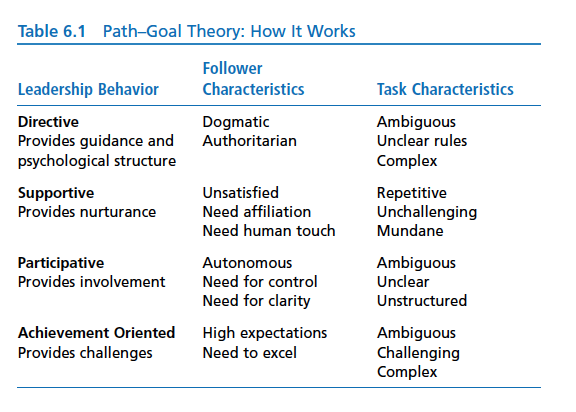

provides direction about how leaders can help followers to accomplish their work in a satisfactory manner. Table 6.1 illustrates how leadership behaviors are related to follower and task characteristics in path–goal theory.

Theoretically, the path–goal approach suggests that leaders need to choose a leadership style that best fits the needs of followers and the work they are doing. The theory predicts that a directive style of leadership is best in situations in which followers are dogmatic and authoritarian, the task demands are ambiguous, the organizational rules are unclear, and the task is complex. In these situations, directive leadership complements the work by providing guidance and psychological structure for followers (House & Mitchell, 1974, p. 90).

For tasks that are structured, unsatisfying, or frustrating, path–goal theory suggests that leaders should use a supportive style. The supportive style pro- vides what is missing by nurturing followers when they are engaged in tasks that are repetitive and unchallenging. Supportive leadership offers a sense of human touch for followers engaged in mundane, mechanized activity.

Participative leadership is considered best when a task is ambiguous: Participation gives greater clarity to how certain paths lead to certain goals, and helps followers learn what leads to what (House & Mitchell, 1974, p. 92).

Theoretically, the path–goal approach suggests that leaders need to choose a leadership style that best fits the needs of followers and the work they are doing. The theory predicts that a directive style of leadership is best in situations in which followers are dogmatic and authoritarian, the task demands are ambiguous, the organizational rules are unclear, and the task is complex. In these situations, directive leadership complements the work by providing guidance and psychological structure for followers (House & Mitchell, 1974, p. 90).

For tasks that are structured, unsatisfying, or frustrating, path–goal theory suggests that leaders should use a supportive style. The supportive style pro- vides what is missing by nurturing followers when they are engaged in tasks that are repetitive and unchallenging. Supportive leadership offers a sense of human touch for followers engaged in mundane, mechanized activity.

Participative leadership is considered best when a task is ambiguous: Participation gives greater clarity to how certain paths lead to certain goals, and helps followers learn what leads to what (House & Mitchell, 1974, p. 92).

In addition, participative leadership has a positive impact when followers are autonomous and have a strong need for control because this kind of follower responds favorably to being involved in decision making and in the structuring of work.

Furthermore, path–goal theory predicts that achievement-oriented leadership is most effective in settings in which followers are required to perform ambiguous tasks. In settings such as these, leaders who challenge and set high standards for followers raise followers’ confidence that they have the ability to reach their goals. In effect, achievement-oriented leadership helps followers feel that their efforts will result in effective performance. In set- tings where the task is more structured and less ambiguous, however, achievement-oriented leadership appears to be unrelated to followers’ expec- tations about their work efforts.

Pragmatically, path–goal theory is straightforward. An effective leader has to attend to the needs of followers. The leader should help followers to define their goals and the paths they want to take in reaching those goals. When obstacles arise, the leader needs to help followers confront them. This may mean helping the follower around the obstacle, or it may mean remov- ing the obstacle. The leader’s job is to help followers reach their goals by directing, guiding, and coaching them along the way.

Strengths

Path–goal theory has several positive features. First, path–goal theory pro-vides a useful theoretical framework for understanding how various leadership behaviors affect followers’ satisfaction and work performance. It was one of the first theories to specify four conceptually distinct varieties of leadership (e.g., directive, supportive, participative, and achievement ori- ented), expanding the focus of prior research, which dealt exclusively with task- and relationship-oriented behaviors ( Jermier, 1996). The path–goal approach was also one of the first situational contingency theories of leadership to explain how task and follower characteristics affect the impact of leadership on follower performance. The framework provided in path–goal theory informs leaders about how to choose an appropriate leadership style based on the various demands of the task and the type of followers being asked to do the task.

A second positive feature of path–goal theory is that it attempts to integrate the motivation principles of expectancy theory into a theory of leadership.

This makes path–goal theory unique because no other leadership approach deals directly with motivation in this way. Path–goal theory forces us continually to ask questions such as these about follower motivation: How can I motivate followers to feel that they have the ability to do the work? How can I help them feel that if they successfully do their work, they will be rewarded? What can I do to improve the payoffs that followers expect from their work? Path–goal theory is designed to keep these kinds of questions, which address issues of motivation, at the forefront of the leader’s mind.

A third strength, and perhaps its greatest, is that path–goal theory provides a model that in certain ways is very practical. The representation of the model (see Figure 6.1) underscores and highlights the important ways leaders help followers. It shouts out for leaders to clarify the paths to the goals and remove or help followers around the obstacles to the goals. In its simplest form, the theory reminds leaders that the overarching purpose of leadership is to guide and coach followers as they move along the path to achieve a goal.

Criticisms

Although path–goal theory has various strengths, it also has several identifiable weaknesses. First, path–goal theory is so complex and incorporates so many different aspects of leadership that interpreting the theory can be confusing. For example, path–goal theory makes predictions about which of four different leadership styles is appropriate for tasks with different degrees of structure, for goals with different levels of clarity, for followers at different levels of ability, and for organizations with different degrees of formal authority. To say the least, it is a daunting task to incorporate all of these factors simultaneously into one’s selection of a preferred leadership style. Because the scope of path–goal theory is so broad and encompasses so many different interrelated sets of assumptions, it is difficult to use this theory fully in trying to improve the leadership process in a given organizational context.

A second limitation of path–goal theory is that it has received only partial support from the many empirical research studies that have been conducted to test its validity (House & Mitchell, 1974; Indvik, 1986; Schriesheim, Castro, Zhou, & DeChurch, 2006; Schriesheim & Kerr, 1977; Schriesheim & Schriesheim, 1980; Stinson & Johnson, 1975; Wofford & Liska, 1993). For example, some research supports the prediction that leader directiveness is positively related to follower satisfaction when tasks are ambiguous, but

other research has failed to confirm this relationship. Furthermore, not all aspects of the theory have been given equal attention. A great deal of research has been designed to study directive and supportive leadership, but fewer studies address participative and achievement-oriented leadership. The claims of path–goal theory remain tentative because the research findings to date do not provide a full and consistent picture of the basic assumptions and corollaries of path–goal theory (Evans, 1996; Jermier, 1996; Schriesheim & Neider, 1996).

Another criticism of path–goal theory is that it fails to explain adequately the relationship between leadership behavior and follower motivation. Path–goal theory is unique in that it incorporates the tenets of expectancy theory; however, it does not go far enough in explicating how leadership is related to these tenets. The principles of expectancy theory suggest that followers will be motivated if they feel competent and trust that their efforts will get results, but path–goal theory does not describe how a leader could use various styles directly to help followers feel competent or assured of success. For example, path–goal theory does not explain how directive leadership during ambiguous tasks increases follower motivation. Similarly, it does not explain how supportive leadership during tedious work relates to follower motivation. The result is that the practitioner is left with an inadequate understanding of how her or his leadership will affect followers’ expectations about their work.

A final criticism that can be made of path–goal theory concerns a practical outcome of the theory. Path–goal theory suggests that it is important for leaders to provide coaching, guidance, and direction for followers, to help followers define and clarify goals, and to help followers around obstacles as they attempt to reach their goals. In effect, this approach treats leadership as a one-way event: The leader affects the follower. The potential difficulty in this type of “helping” leadership is that followers may easily become dependent on the leader to accomplish their work. Path–goal theory places a great deal of responsibility on leaders and much less on followers. Over time, this kind of leadership could be counterproductive because it promotes dependency and fails to recognize the full abilities of followers.

Application

Path–goal theory is not an approach to leadership for which many management training programs have been developed. You will not find many seminars with titles such as “Improving Your Path–Goal Leadership” or

“Assessing Your Skills in Path–Goal Leadership,” either. Nevertheless, path–goal theory does offer significant insights that can be applied in ongo- ing settings to improve one’s leadership.

Path–goal theory provides a set of general recommendations based on the characteristics of followers and tasks for how leaders should act in various situations if they want to be effective. It informs us about when to be directive, supportive, participative, or achievement oriented. For instance, the theory suggests that leaders should be directive when tasks are complex, and the leader should give support when tasks are dull. Similarly, it suggests that leaders should be participative when followers need control and that leaders should be achievement oriented when followers need to excel. In a general way, path–goal theory offers leaders a road map that gives directions about ways to improve follower satisfaction and performance.

The principles of path–goal theory can be used by leaders at all levels in the organization and for all types of tasks. To apply path–goal theory, a leader must carefully assess the followers and their tasks, and then choose an appropriate leadership style to match those characteristics. If followers are feeling insecure about doing a task, the leader needs to adopt a style that builds follower confidence. For example, in a university setting where a junior faculty member feels apprehensive about his or her teaching and research, a department chair should give supportive leadership. By giving care and support, the chair helps the junior faculty member gain a sense of confidence about his or her ability to perform the work (Bess & Goldman, 2001). If followers are uncertain whether their efforts will result in reaching their goals, the leader needs to prove to them that their efforts will be rewarded. As discussed earlier in the chapter, path–goal theory is useful because it continually reminds leaders that their central purpose is to help followers define their goals and then to help followers reach their goals in the most efficient manner.

Case Studies

The following cases provide descriptions of various situations in which a leader

is attempting to apply path–goal theory. Two of the cases, Cases 6.1 and 6.2, are from traditional business

contexts; the third, Case 6.3, is from an

academic perspective of teaching orchestra students. As you read the cases, try to apply the principles of

path–goal theory to determine the degree

to which you think the leaders in the cases have done a good job of using this theory.

Case 6.1

Three Shifts, Three Supervisors

Brako is a small manufacturing company that produces parts for the automobile industry. The company has several patents on parts that fit in the brake assembly of nearly all domestic and foreign cars. Each year, the company produces 3 million parts that it ships to assembly plants throughout the world. To produce the parts, Brako runs three shifts with about 40 workers on each shift.

The supervisors for the three shifts (Art, Bob, and Carol) are experienced employees, and each has been with the company for more than 20 years. The supervisors appear satisfied with their work and have reported no major difficulty in supervising employees at Brako.

Art supervises the first shift. Employees describe him as being a very hands-on type of leader. He gets very involved in the day-to-day operations of the facility. Workers joke that Art knows to the milligram the amount of raw materials the company has on hand at any given time. Art often can be found walking through the plant and reminding people of the correct procedures to follow in doing their work. Even for those working on the production line, Art always has some directions and reminders.

Workers on the first shift have few negative comments to make about Art’s leadership. However, they are negative about many other aspects of their work. Most of the work on this shift is very straightforward and repetitive; as a result, it is monotonous. The rules for working on the production line or in the packaging area are all clearly spelled out and require no independent decision making on the part of workers. Workers simply need to show up and go through the motions. On lunch breaks, workers often are heard complaining about how bored they are doing the same old thing over and over. Workers do not criticize Art, but they do not think he really understands their situation.

Bob supervises the second shift. He really enjoys working at Brako and wants all the workers on the afternoon shift to enjoy their work as well. Bob is a people-oriented supervisor whom workers describe as very genuine and caring. Hardly a day goes by that Bob does not post a message about someone’s birthday or someone’s personal accomplishment. Bob works hard at creating camaraderie, including sponsoring a company softball team, taking people out to lunch, and having people over to his house for social events.

Despite Bob’s personableness, absenteeism and turnover are highest on the second shift. The second shift is responsible for setting up the machines and equipment when changes are made from making one part to making another. In addition, the second shift is responsible for the complex computer programs that monitor the machines.

Workers on the second shift take a lot of heat from others at Brako for not doing a good job. Workers on the second shift feel pressure because it is not always easy to figure out how to do their tasks. Each setup is different and entails different procedures. Although the computer is extremely helpful when it is calibrated appropriately to the task, it can be extremely problematic when the software it uses is off the mark. Workers have complained to Bob and upper management many times about the difficulty of their jobs.

Carol supervises the third shift. Her style is different from that of the others at Brako. Carol routinely has meetings, which she labels troubleshooting sessions, for the purpose of identifying problems workers are experiencing. Any time there is a glitch on the production line, Carol wants to know about it so she can help workers find a solution. If workers cannot do a particular job, she shows them how. For those who are uncertain of their competencies, Carol gives reassurance. Carol tries to spend time with each worker and help the workers focus on their personal goals. In addition, she stresses company goals and the rewards that are available if workers are able to make the grade.

People on the third shift like to work for Carol. They find she is good at helping them do their job. They say she has a wonderful knack for making everything fall into place. When there are problems, she addresses them. When workers feel down, she builds them up. Carol was described by one worker as an interesting mixture of part parent, part coach, and part manufacturing expert. Upper management at Brako is pleased with Carol’s leadership, but they have experienced problems repeatedly when workers from Carol’s shift have been rotated to other shifts at Brako.

Questions

1. Based on the principles of path–goal theory, describe why Art and Bob appear to be less effective than Carol.

2. How does the leadership of each of the three supervisors affect the motivation of their respective followers?

3. If you were consulting with Brako about leadership, what changes and recommendations would you make regarding the supervision of Art, Bob, and Carol?

Case 6.2

Direction for Some, Support for Others

fDaniel Shivitz is the manager of a small business called The Copy Center, which is located near a large university. The Copy Center employs about 18 people, most of whom work part-time while going to school full-time. The store caters to the university community by specializing in course packs, but it also provides desktop publishing and standard copying services. It has three large, state-of-the-art copy machines and several computer workstations.

There are two other national chain copy stores in the immediate vicinity of The Copy Center, yet this store does more business than both of the other stores combined. A major factor contributing to the success of this store is Daniel’s leadership style.

One of the things that stand out about Daniel is the way he works with his part-time staff. Most of them are students, who have to schedule their work hours around their class schedules, and Daniel has a reputation of being really helpful with working out schedule conflicts. No conflict is too small for Daniel, who is always willing to juggle schedules to meet the needs of everyone. Students talk about how much they feel included and like the spirit at The Copy Center. It is as if Daniel makes the store like a second family for them.

Work at The Copy Center divides itself into two main areas: duplicating services and desktop publishing. In both areas, Daniel’s leadership is effective.

Duplicating is a straightforward operation that entails taking a customer’s originals and making copies of them. Because this job is tedious, Daniel goes out of his way to help the staff make it tolerable. He promotes a friendly work atmosphere by doing such things as letting the staff wear casual attire, letting them choose their own background music, and letting them be a bit wild on the job. Daniel spends a lot of time each day conversing informally with each employee; he also welcomes staff talking with each other. Daniel has a knack for making each worker feel significant even when the work is insignificant. He promotes camaraderie among his staff, and he is not afraid to become involved in their activities.

The desktop publishing area is more complex than duplicating. It involves creating business forms, advertising pieces, and résumés for customers. Working in desktop publishing requires skills in writing, editing, design, and layout. It is challenging work because it is not always easy to satisfy customers’ needs. Most of the employees in this area are full-time workers.

Through the years, Daniel has found that employees who work best in desktop publishing are a unique type of person, very different from those who work in duplicating. They are usually quite independent, self-assured, and self-motivated. In supervising them, Daniel gives them a lot of space, is available when they need help, but otherwise leaves them alone.

Daniel likes the role of being the resource person for these employees. For example, if an employee is having difficulty on a customer’s project, he willingly joins the employee in troubleshooting the problem. Similarly, if one of the staff is having problems with a software program, Daniel is quick to offer his technical expertise. Because the employees in desktop publishing are self-directed, Daniel spends far less time with them than with those who work in duplicating.

Overall, Daniel feels successful with his leadership at The Copy Center. Profits for the store continue to grow each year, and its reputation for high-quality service is widespread.

Questions

1. According to path–goal theory, why is Daniel an effective leader?

2. How does his leadership style affect the motivation of employees at The Copy Center?

3. How do characteristics of the task and the followers influence Daniel’s leadership?

4. One of the principles of path–goal theory is to make the end goal valuable to workers. What could Daniel do to improve follower motivation in this area?

Case 6.3

Playing in the Orchestra

Martina Bates is the newly hired orchestra teacher at Middletown School District in rural Sparta, Kansas. After graduating from the Juilliard School of Music, Martina had intended to play violin professionally, but when no jobs became available, she accepted an offer to teach orchestra in her hometown, believing it would be a good place to hone her skills until a professional position became available.

Being the orchestra instructor at Middletown is challenging because it involves teaching music classes, directing the high school orchestra, and directing both the middle school and grade school orchestra programs. When classes started, Martina hit the ground running and found she liked teaching, exhilarated by her work with students. After her first year, however, she is having misgivings about her decision to teach. Most of all, she is feeling troubled by how different students are in each of the three programs, and how her leadership does not seem to be effective with all the students.

Running the elementary orchestra program is demanding, but fun. A lot of parents want their children to play an instrument, so the turnout for orchestra is really strong, and it is the largest of the three Middletown programs. Many students have never held an instrument before, so teaching them is quite a challenge. Learning to make the cornet sound like a cornet or moving the bow of a cello so it sounds like a cello is a huge undertaking. Whether it is drums, bass viol, clarinet, or saxophone, Martina patiently shows the kids how to play and consistently compliments them every small step of the way. First and foremost, she wants each child to feel like he or she can “do it.” She instructs her students with great detail about how to hold the instruments, position their tongues, and read notes. They respond well to Martina’s kindness and forbearance, and the parents are thrilled. The orchestra’s spring concert had many wild sounds but was also wildly successful, with excited children and happy parents.

The middle school orchestra is somewhat smaller in size and presents different challenges for Martina. The students in this orchestra are starting to sound good on their instruments and are willing to play together as a group, but some of them are becoming disinterested and want to quit. Martina uses a different style of leadership with the middle schoolers, stressing practice and challenging students to improve their skills. At this level, students are placed in “chairs” for each instrument. The best players sit in the first chair, the next best are second chair, and so on down to the last chair. Each week, the students engage in “challenges” for the chairs. If students practice hard and improve, they can advance to a higher chair; students who don’t practice can slip down to a lower chair. Martina puts up charts to track students’ practice hours, and when they reach established goals, they can choose a reward from “the grab bag of goodies,” which has candy, trinkets, and gift cards. Never knowing what their prize will be motivates the students, especially as they all want to get the gift cards. Although some kids avoid practice because they find it tedious and boring, many enjoy it because it improves their performance, to say nothing about the chance to get a prize. The spring concert for this group is Martina’s favorite, because the sounds are better and the students are interested in playing well.

Middletown’s high school orchestra is actually very small, which is surprising to Martina. Why does she have nearly a hundred kids in the elementary orchestra and less than half that number in the high school program? She likes teaching the high school students, but they do not seem too excited about playing. Because she is highly trained herself, Martina likes to show students advanced techniques and give them challenging music to play. She spends hours listening to each student play, providing individualized feedback that, unfortunately in many cases, doesn’t seem to have any impact on the students. For example, Chris Trotter, who plays third-chair trumpet, is considering dropping orchestra to go out for cross-country. Similarly, Lisa Weiss, who is first-chair flute, seems bored and may quit the orchestra to get a part-time job. Martina is frustrated and baffled; why would these students want to quit? They are pretty good musicians, and most of them are willing to practice. The students have such wonderful potential but don’t seem to want to use it. Students profess to liking Martina, but many of them just don’t seem to want to be in the orchestra.

Questions

1. Path–goal leadership is about how leaders can help followers reach their goals. Generally, what are the goals for the students in each of the different orchestras? What obstacles do they face? In what way does Martina help them address obstacles and reach their goals?

2. Based on the principles of expectancy theory described in the chapter, why is Martina effective with the elementary and middle school orchestras? Why do both of these groups seem motivated to play for her? In what ways did she change her leadership style for the middle schoolers?

3. Martina’s competencies as a musician do not seem to help her with the students who are becoming disinterested in orchestra. Why? Using ideas from expectancy theory, what would you advise her to do to improve her leadership with the high school orchestra?

4. Achievement-oriented leadership is one of the four major kinds of path–goal leadership. For which of the three orchestras do you think this style would be most effective? Discuss.

Leadership Instrument

Because the path–goal theory was developed as a complex set of theoretical assumptions to direct researchers in developing new leadership theory, it has used many different instruments to measure the leadership process. The Path–Goal Leadership Questionnaire has been useful in measuring and learning about important aspects of path–goal leadership (Indvik, 1985, 1988). This questionnaire provides information for respondents about four different leadership styles: directive, supportive, participative, and achievement oriented. Respondents’ scores on each of the different styles provide them with information on their strong and weak styles and the relative importance they place on each of the styles.

To understand the path–goal questionnaire better, it may be useful to analyze a hypothetical set of scores. For example, hypothesize that your scores on the questionnaire were 29 for directive, which is high; 22 for supportive, which is low; 21 for participative, which is average; and 25 for achievement, which is high. These scores suggest that you are a leader who is typically more directive and achievement oriented than most other leaders, less supportive than other leaders, and quite similar to other leaders in the degree to which you act participatively.

According to the principles of path–goal theory, if your scores matched these hypothetical scores, you would be effective in situations where the tasks and procedures are unclear and your followers have a need for certainty. You would be less effective in work settings that are structured and unchalleng- ing. In addition, you would be moderately effective in ambiguous situations with followers who want control. Last, you would do very well in uncertain situations where you could set high standards, challenge followers to meet these standards, and help them feel confident in their abilities.

In addition to the Path–Goal Leadership Questionnaire, leadership researchers have commonly used multiple instruments to study path–goal theory, including measures of task structure, locus of control, follower expectancies, and follower satisfaction. Although the primary use of these instruments has been for theory building, many of the instruments offer valuable information related to practical leadership issues.

Path–Goal Leadership Questionnaire

Instructions: This questionnaire contains questions about different styles of path–

goal leadership. Indicate how often each statement is true of your own behavior.

Key: 1 = Never 2 = Hardly ever 3 = Seldom 4 = Occasionally 5 = Often

6 = Usually 7 = Always

1. I let followers know what is expected of them. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

2. I maintain a friendly working relationship

with followers.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

3. I consult with followers when facing a problem.1 2 3 4 5 6 7

4. I listen receptively to followers’ ideas and

suggestions.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

5. I inform followers about what needs to be

done and how it needs to be done.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

6. I let followers know that I expect them to perform

at their highest level.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

7. I act without consulting my followers. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

8. I do little things to make it pleasant to be a

member of the group.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

9. I ask followers to follow standard rules and

regulations.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

10. I set goals for followers’ performance that are

quite challenging.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

11. I say things that hurt followers’ personal feelings.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

12. I ask for suggestions from followers concerning

how to carry out assignments.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

13. I encourage continual improvement in followers’

performance.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

14. I explain the level of performance that is

expected of followers.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

15. I help followers overcome problems that stop

them from carrying out their tasks.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

16. I show that I have doubts about followers’

ability to meet most objectives.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

17. I ask followers for suggestions on what assignments

should be made.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

18. I give vague explanations of what is expected

of followers on the job.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

19. I consistently set challenging goals for followers

to attain.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

20. I behave in a manner that is thoughtful of followers’

personal needs.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Scoring

1. Reverse the scores for Items 7, 11, 16, and 18.

2. D irective style: Sum of scores on Items 1, 5, 9, 14, and 18.

3. Supportive style: Sum of scores on Items 2, 8, 11, 15, and 20.

4. Participative style: Sum of scores on Items 3, 4, 7, 12, and 17.

5. Achievement-oriented style: Sum of scores on Items 6, 10, 13, 16, and 19.

Scoring Interpretation

• Directive style: A common score is 23, scores above 28 are considered

high, and scores below 18 are considered low.

• Supportive style: A common score is 28, scores above 33 are considered

high, and scores below 23 are considered low.

• Participative style: A common score is 21, scores above 26 are

considered high, and scores below 16 are considered low.

• Achievement-oriented style: A common score is 19, scores above 24

are considered high, and scores below 14 are considered low.

The scores you received on the Path–Goal Leadership Questionnaire provide

information about which styles of leadership you use most often

and which you use less often. In addition, you can use these scores to

assess your use of each style relative to your use of the other styles.

Summary

Path–goal theory was developed to explain how leaders motivate followers to be productive and satisfied with their work. It is a contingency approach to leadership because effectiveness depends on the fit between the leader’s behavior and the characteristics of followers and the task.

The basic principles of path–goal theory are derived from expectancy theory, which suggests that followers will be motivated if they feel competent, if they think their efforts will be rewarded, and if they find the payoff for their work valuable. A leader can help followers by selecting a style of leadership (directive, supportive, participative, or achievement oriented) that provides what is missing for followers in a particular work setting. In simple terms, it is the leader’s responsibility to help followers reach their goals by directing, guiding, and coaching them along the way.

Path–goal theory offers a large set of predictions for how a leader’s style interacts with followers’ needs and the nature of the task. Among other things, it predicts that directive leadership is effective with ambiguous tasks, that supportive leadership is effective for repetitive tasks, that participative leadership is effective when tasks are unclear and followers are autonomous, and that achievement-oriented leadership is effective for challenging tasks.

Path–goal theory has three major strengths. First, it provides a theoretical framework that is useful for understanding how directive, supportive, participative, and achievement-oriented styles of leadership affect the productivity and satisfaction of followers. Second, path–goal theory is unique in that it integrates the motivation principles of expectancy theory into a the- ory of leadership. Third, it provides a practical model that underscores the important ways in which leaders help followers.

On the negative side, four criticisms can be leveled at path–goal theory. First, the scope of path–goal theory encompasses so many interrelated sets of assumptions that it is hard to use this theory in a given organizational setting. Second, research findings to date do not support a full and consistent picture of the claims of the theory. Furthermore, path–goal theory does not show in a clear way how leader behaviors directly affect follower motivation levels. Last, path–goal theory is very leader oriented and fails to recognize the interactional nature of leadership. It does not promote follower involvement in the leadership process.