Textbook Reading: Northouse Chapter 7

Leader–Member Exchange Theory

Description

Most of the leadership theories

discussed thus far in this book have emphasized

leadership from the point of view of the leader (e.g., trait approach, skills approach, and style

approach) or the follower and the context (e.g., Situational Leadershipâ and path–goal theory). Leader– member exchange (LMX) theory takes still another approach and

conceptualizes leadership as a process

that is centered on the interactions between leaders and followers.

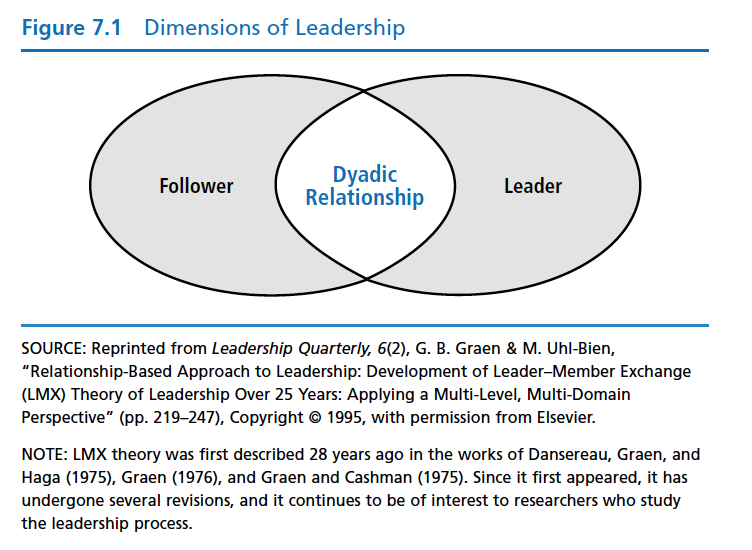

As Figure 7.1 illustrates, LMX theory makes the dyadic relationship between leaders and followers

the focal point of the leadership process.

leadership as a process

that is centered on the interactions between leaders and followers.

As Figure 7.1 illustrates, LMX theory makes the dyadic relationship between leaders and followers

the focal point of the leadership process.

Before LMX theory, researchers treated leadership as something leaders did toward all of their followers. This assumption implied that leaders treated followers in a collective way, as a group, using an average leadership style. LMX theory challenged this assumption and directed researchers’ attention to the differences that might exist between the leader and each of the leader’s followers.

Early Studies

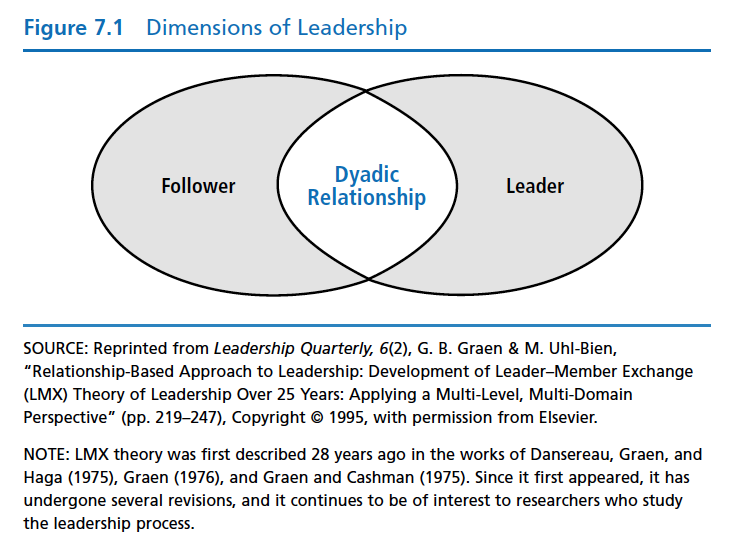

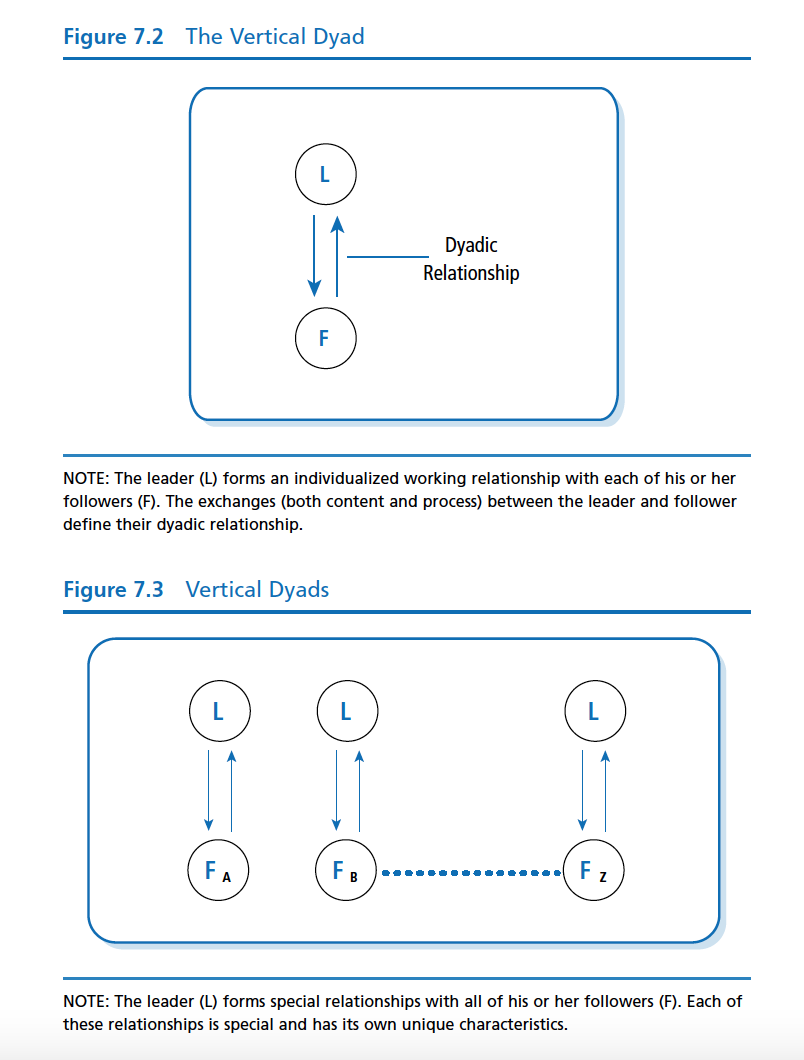

In the first studies of exchange theory, which was then called vertical dyad linkage (VDL) theory, researchers focused on the nature of the vertical linkages leaders formed with each of their followers (Figure 7.2). A leader’s relationship to the work unit as a whole was viewed as a series of vertical dyads (Figure 7.3).

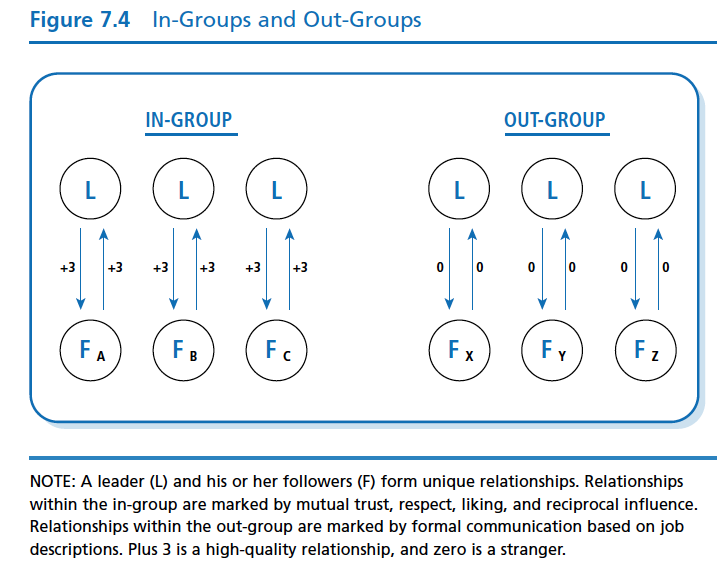

In assessing the characteristics of these vertical dyads, researchers found two general types of linkages (or relationships): those that were based on expanded and negotiated role responsibilities (extra-roles), which were called the in- group, and those that were based on the formal employment contract (defined roles), which were called the out-group (Figure 7.4).

Within an organizational work unit, followers become a part of the in-group or the out-group based on how well they work with the leader and how well the leader works with them. Personality and other personal characteristics are related to this process (Dansereau, Graen, & Haga, 1975). In addition, membership in one group or the other is based on how followers involve themselves in expanding their role responsibilities with the leader (Graen, 1976). Followers who are interested in negotiating with the leader what they are willing to do for the group can become a part of the in-group. These negotiations involve exchanges in which followers do certain activities that go beyond their formal job descriptions, and the leader, in turn, does more for these followers. If followers are not interested in taking on new and different job responsibilities, they become a part of the out-group.

Followers in the in-group receive more information, influence, confidence, and concern from their leaders than do out-group followers (Dansereau et al., 1975). In addition, they are more dependable, more highly involved,

and more communicative than out-group followers (Dansereau et al., 1975). Whereas in-group members do extra things for the leader and the leader does the same for them, followers in the out-group are less compatible with the leader and usually just come to work, do their job, and go home.

Later Studies

After the first set of studies, there was a shift in the focus of LMX theory. Whereas the initial studies of this theory addressed primarily the nature of the differences between in-groups and out-groups, a subsequent line of research addressed how LMX theory was related to organizational effectiveness.

Specifically, these studies focus on how the quality of leader–member exchanges was related to positive outcomes for leaders, followers, groups, and the organization in general (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995).

Researchers found that high-quality leader–member exchanges produced less employee turnover, more positive performance evaluations, higher frequency of promotions, greater organizational commitment, more desirable work assignments, better job attitudes, more attention and support from the leader, greater participation, and faster career progress over 25 years (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Liden, Wayne, & Stilwell, 1993).

In a meta-analysis of 164 LMX studies, Gerstner and Day (1997) found that LMX was consistently related to member job performance, satisfaction (overall and supervisory), commitment, role conflict and clarity, and turnover

intentions. In addition, they found strong support in these studies for the psychometric properties of the LMX 7 Questionnaire. For purposes of research, they highlighted the importance of measuring LMX from the perspective of both the leader and the follower.

Based on a review of 130 studies of LMX research conducted since 2002, Anand, Hu, Liden, and Vidyarthi (2011) found that interest in studying leader–member exchange has not diminished. A large majority of these studies (70%) examined the antecedents and outcomes of leader–member exchange. The research trends show increased attention to the context surrounding LMX relationships (e.g., group dynamics), analyzing leader–member exchange from individual and group levels, and studying leader–member exchange with non-U.S. samples.

For example, using a sample of employees in a variety of jobs in Israeli orga- nizations, Atwater and Carmeli (2009) examined the connection between employees’ perceptions of leader–member exchange and their energy and creativity at work. They found that perceived high-quality leader–member exchange was positively related to feelings of energy in employees, which, in turn, was related to greater involvement in creative work. LMX theory was not directly associated with creativity, but it served as a mechanism to nurture people’s feelings, which then enhanced their creativity.

Ilies, Nahrgang, and Morgeson (2007) did a meta-analysis of 51 research studies that examined the relationship between LMX and employee citizenship behaviors. Citizenship behaviors are discretionary employee behaviors that go beyond the prescribed role, job description, or reward system (Katz, 1964; Organ, 1988). They found a positive relationship between the quality of leader–member relationships and citizenship behaviors. In other words, followers who had higher-quality relationships with their leaders were more likely to engage in more discretionary (positive “payback”) behaviors that benefited the leader and the organization.

Researchers have also studied how LMX theory is related to empowerment. Harris, Wheeler, and Kacmar (2009) explored how empowerment moder- ates the impact of leader–member exchange on job outcomes such as job satisfaction, turnover, job performance, and organizational citizenship behaviors. Based on two samples of college alumni, they found that empowerment and leader–member exchange quality had a slight synergistic effect on job outcomes. The quality of leader–member exchange mattered most for employees who felt little empowerment. For these employees, high-quality leader–member exchange appeared to compensate for the drawbacks of not being empowered.

In essence, the aforementioned findings clearly illustrate that organizations stand to gain much from having leaders who can create good working rela- tionships. When leaders and followers have good exchanges, they feel better and accomplish more, and the organization prospers.

Leadership Making

Research of LMX theory has also focused on how exchanges between leaders and followers can be used for leadership making (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1991). Leadership making is a prescriptive approach to leadership emphasizing that leaders should develop high-quality exchanges with all of their followers rather than just a few. It attempts to make every follower feel as if he or she is a part of the in-group and, by so doing, avoids the inequities and negative implications of being in an out-group. In general, leadership making promotes partnerships in which the leader tries to build effective dyads with all followers in the work unit (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995). In addition, leadership making suggests that leaders can create networks of partnerships throughout the organization, which will benefit the organization’s goals and the leader’s own career progress.

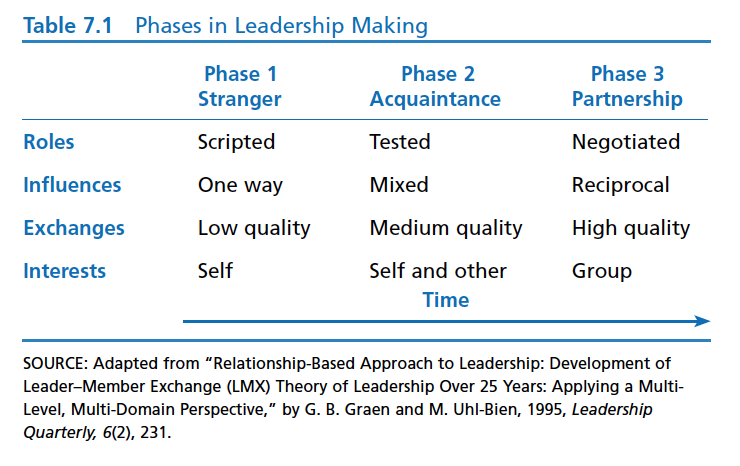

Graen and Uhl-Bien (1991) suggested that leadership making develops progressively over time in three phases: (1) the stranger phase, (2) the acquaintance phase, and (3) the mature partnership phase (Table 7.1). During Phase 1, the stranger phase, the interactions in the leader–follower dyad generally are rule bound, relying heavily on contractual relationships. Leaders and followers relate to each other within prescribed organizational roles. They have lower-quality exchanges, similar to those of out-group members discussed earlier in the chapter. The follower complies with the formal leader, who has hierarchical status for the purpose of achieving the economic rewards the leader controls. The motives of the follower during the stranger phase are directed toward self- interest rather than toward the good of the group (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995).

In a study of the early stages of leader–member relationship development, Nahrgang, Morgeson, and Ilies (2009) found that leaders look for followers who exhibit enthusiasm, participation, gregariousness, and extraversion. In contrast, followers look for leaders who are pleasant, trusting, cooperative, and agreeable. Leader extraversion did not influence relationship quality for the followers, and follower agreeableness did not influence relationship quality for the leaders. A key predictor of relationship quality for both leaders and followers was behaviors such as performance.

Phase 2, the acquaintance phase, begins with an offer by the leader or the follower for improved career-oriented social exchanges, which involve sharing more resources and personal or work-related information. It is a testing period

for both the leader and the follower to assess whether the follower is interested in taking on more roles and responsibilities and to assess whether the leader is willing to provide new challenges for followers. During this time, dyads shift away from interactions that are governed strictly by job descriptions and defined roles and move toward new ways of relating. As measured by LMX theory, it could be said that the quality of their exchanges has improved to medium quality. Successful dyads in the acquaintance phase begin to develop greater trust and respect for each other. They also tend to focus less on their own self-interests and more on the purposes and goals of the group.

Phase 3, mature partnership, is marked by high-quality leader–member exchanges. People who have progressed to this stage in their relationships experience a high degree of mutual trust, respect, and obligation toward each other. They have tested their relationship and found that they can depend on each other. In mature partnerships, there is a high degree of reciprocity between leaders and followers: Each affects and is affected by the other. For example, in a study of 75 bank managers and 58 engineering managers, Schriesheim, Castro, Zhou, and Yammarino (2001) found that good leader– member relations were more egalitarian and that influence and control were more evenly balanced between the supervisor and the follower. In addition, during Phase 3, members may depend on each other for favors and special assistance. For example, leaders may rely on followers to do extra assignments, and followers may rely on leaders for needed support or encouragement. The point is that leaders and followers are tied together in productive ways that go well beyond a traditional hierarchically defined work relationship. They

have developed an extremely effective way of relating that produces positive outcomes for themselves and the organization. In effect, partnerships are transformational in that they assist leaders and followers in moving beyond their own self-interests to accomplish the greater good of the team and organization (see Chapter 8).

The benefits for employees who develop high-quality leader–member relationships include preferential treatment, increased job-related communication, ample access to supervisors, and increased performance-related feedback (Harris et al., 2009). The disadvantages for those with low-quality leader– member relationships include limited trust and support from supervisors and few benefits outside the employment contract (Harris et al., 2009). To evaluate leader–member exchanges, researchers typically use a brief questionnaire that asks leaders and followers to report on the effectiveness of their working relationships. The questionnaire assesses the degree to which respondents express respect, trust, and obligation in their exchanges with others. At the end of this chapter, a version of the LMX questionnaire is provided for you to take for the purpose of analyzing some of your own leader–member relationships.

How does LMX theory work?

LMX theory works in two ways: It describes leadership, and it prescribes leadership. In both instances, the central concept is the dyadic relationship that a leader forms with each of the leader’s followers. Descriptively, LMX theory suggests that it is important to recognize the existence of in-groups and out-groups within a group or an organization.

The differences in how goals are accomplished by in-groups and out-groups are substantial. Working with an in-group allows a leader to accomplish more work in a more effective manner than he or she can accomplish working without one. In-group members are willing to do more than is required in their job description and look for innovative ways to advance the group’s goals. In response to their extra effort and devotion, leaders give them more responsibilities and more opportunities. Leaders also give in-group members more of their time and support.

Out-group members act quite differently than in-group members. Rather than trying to do extra work, out-group members operate strictly within their prescribed organizational roles. They do what is required of them but nothing more. Leaders treat out-group members fairly and according to the formal contract, but they do not give them special attention. For their efforts,out-group members receive the standard benefits as defined in the job description.

Prescriptively, LMX theory is best understood within the leadership-making model of Graen and Uhl-Bien (1991). Graen and Uhl-Bien advocated that leaders should create a special relationship with all followers, similar to the relationships described as in-group relationships. Leaders should offer each follower the opportunity to take on new roles and responsibilities. Furthermore, leaders should nurture high-quality exchanges with their followers. Rather than focusing on the differences between in-group and out-group members, the leadership-making model suggests that leaders should look for ways to build trust and respect with all of their followers, thus making the entire work unit an in-group. In addition, leaders should look beyond their own work unit and create high-quality partnerships with people throughout the organization.

Whether descriptive or prescriptive, LMX theory works by focusing our attention on the special, unique relationship that leaders can create with others. When these relationships are of high quality, the goals of the leader, the followers, and the organization are all advanced.

Strengths

LMX theory makes several positive contributions to our understanding of the leadership process. First, it is a strong descriptive theory. Intuitively, it makes sense to describe work units in terms of those who contribute more and those who contribute less (or the bare minimum) to the organization. Anyone who has ever worked in an organization has felt the presence of in-groups and out-groups. Despite the potential harm of out-groups, we all know that leaders have special relationships with certain people who do more and get more. We may not like this because it seems unfair, but it is a reality, and the LMX theory has accurately described this situation. LMX theory validates our experience of how people within organizations relate to each other and the leader. Some contribute more and receive more; others contribute less and get less.

Second, LMX theory is unique because it is the only leadership approach that makes the concept of the dyadic relationship the centerpiece of the leadership process. Other approaches emphasize the characteristics of leaders, followers, contexts, or a combination of these, but none of them addresses the specific relationships between the leader and each follower. LMX theory underscores that effective leadership is contingent on effective leader– member exchanges.

Third, LMX theory is noteworthy because it directs our attention to the importance of communication in leadership. The high-quality exchanges advocated in LMX theory are inextricably bound to effective communication. Communication is the vehicle through which leaders and followers create, nurture, and sustain useful exchanges. Effective leadership occurs when the communication of leaders and followers is characterized by mutual trust, respect, and commitment.

Fourth, LMX theory provides an important alert for leaders. It warns leaders to avoid letting their conscious or unconscious biases influence who is invited into the in-group (e.g., biases regarding race, gender, ethnicity, religion, or age). The principles outlined in LMX theory serve as a good reminder for leaders to be fair and equal in how they approach each of their followers.

Finally, a large body of research substantiates how the practice of LMX theory is related to positive organizational outcomes. In a review of this research, Graen and Uhl-Bien (1995) pointed out that leader–member exchange is related to performance, organizational commitment, job climate, innovation, organizational citizenship behavior, empowerment, procedural and distributive justice, career progress, and many other important organizational variables. By linking the use of LMX theory to real outcomes, researchers have been able to validate the theory and increase its practical value.

Criticisms

LMX theory also has some limitations. First, on the surface, leader–member exchange in its initial formulation (vertical dyad linkage theory) runs counter to the basic human value of fairness. Throughout our lives, beginning when we are very young, we are taught to try to get along with everyone and to treat everyone equally. We have been taught that it is wrong to form in- groups or cliques because they are harmful to those who cannot be a part of them. Because LMX theory divides the work unit into two groups and one group receives special attention, it gives the appearance of discrimination against the out-group.

Our culture is replete with examples of people of different genders, ages, cultures, and abilities who have been discriminated against. Although LMX theory was not designed to do so, it supports the development of privileged

groups in the workplace. In so doing, it appears unfair and discriminatory. Furthermore, as reported by McClane (1991), the existence of in-groups and out-groups may have undesirable effects on the group as a whole.

Whether LMX theory actually creates inequalities is questionable (cf. Harter & Evanecky, 2002; Scandura, 1999). If a leader does not intentionally keep out- group members “out,” and if they are free to become members of the in-group, then LMX theory may not create inequalities. However, the theory does not elaborate on strategies for how one gains access to the in-group if one chooses to do so.

Furthermore, LMX theory does not address other fairness issues, such as fol- lowers’ perceptions of the fairness of pay increases and promotion opportunities (distributive justice), decision-making rules (procedural justice), or communication of issues within the organization (interactional justice) (Scandura, 1999). There is a need for further research on how these types of fairness issues affect the development and maintenance of LMX relationships.

A second criticism of LMX theory is that the basic ideas of the theory are not fully developed. For example, the theory does not fully explain how high-quality leader–member exchanges are created (Anand et al., 2011). In the early studies, it was implied that they were formed when a leader found certain followers more compatible in regard to personality, interpersonal skills, or job competencies, but these studies never described the relative importance of these factors or how this process worked (Yukl, 1994). Research has suggested that leaders should work to create high-quality exchanges with all followers, but the guidelines for how this is done are not clearly spelled out. For example, the model on leadership making highlights the importance of role making, incremental influence, and type of reciprocity (see Table 7.1), but it does not explain how these concepts function to build mature partnerships. Similarly, the model strongly promotes building trust, respect, and obligation in leader–follower relationships, but it does not describe the means by which these factors are developed in relationships.

Based on an examination of 147 studies of leader–member exchange, Schriesheim, Castro, and Cogliser (1999) concluded that improved theorization about leader–member exchange and its basic processes is needed. Similarly, in a review of the research on relational leadership, Uhl-Bien, Maslyn, and Ospina (2012) point to the need for further understanding of how high- and low-quality relationships develop in leader–member exchange. Although many studies have been conducted on leader–member exchange, these studies have not resulted in a clear, refined set of definitions, concepts, and propositions about the theory.A third criticism of the theory is that researchers have not adequately explained the contextual factors that may have an impact on LMX relationships (Anand et al., 2011). Since leader–member exchange is often studied in isolation, researchers have not examined the potential impact of other variables on LMX dyads. For example, workplace norms and other organizational culture variables are likely to influence leader–member exchange. There is a need to explore how the surrounding constellations of social networks influence specific LMX relationships and the individuals in those relationships.

Finally, questions have been raised about the measurement of leader– member exchanges in LMX theory (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Schriesheim, Castro, & Cogliser, 1999; Schriesheim, Castro, Zhou, et al., 2001). For example, no empirical studies have used dyadic measures to analyze the LMX process (Schriesheim, Castro, Zhou, et al., 2001). In addition, leader–member exchanges have been measured with different versions of leader–member exchange scales and with different levels of analysis, so the results are not always directly comparable. Furthermore, the content validity and dimensionality of the scales have been questioned (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995; Schriesheim, Castro, Zhou, et al., 2001).

Application

Although LMX theory has not been packaged in a way to be used in standard management training and development programs, it offers many insights that leaders could use to improve their own leadership behavior. Foremost, LMX theory directs leaders to assess their leadership from a relationship perspective. This assessment will sensitize leaders to how in- groups and out-groups develop within their own organization. In addition, LMX theory suggests ways in which leaders can improve their organization by building strong leader–member exchanges with all of their followers.

The ideas set forth in LMX theory can be used by leaders at all levels within an organization. For example, LMX theory could be used to explain how CEOs develop special relationships with select individuals in upper management to develop new strategic and tactical corporate goals. A presidential cabinet is a good example of this. A U.S. president will handpick the 15 people that serve as his or her closest advisers. The cabinet includes the vice president and the heads of 15 executive departments—the secretaries of the Departments of Agriculture, Commerce, Defense, Education, Energy, Health and Human Services, Homeland Security, Housing and Urban Development, Interior, Labor, State, Transportation, Treasury, and Veterans Affairs, as well

as the attorney general. These individuals, in turn, run their own departments in accordance with the goals and philosophy of the president.

On a lower level, LMX theory could be used to explain how line managers in a manufacturing plant use a select few workers to accomplish the production quotas of their work unit. The point is that the ideas presented in LMX theory are applicable throughout organizations.

In addition, the ideas of LMX theory can be used to explain how individuals create leadership networks throughout an organization to help them accomplish work more effectively (Graen & Scandura, 1987). A person with a network of high-quality partnerships can call on many people to help solve problems and advance the goals of the organization.

LMX theory can also be applied in different types of organizations. It applies in volunteer settings as well as traditional business, education, and government settings. Imagine a community leader who heads a volunteer program that assists older adults. To run the program effectively, the leader depends on a few of the volunteers who are more dependable and committed than the rest of the volunteers. This process of working closely with a small cadre of trusted volunteers is explained by the principles of LMX theory. Similarly, a manager in a traditional business setting might use certain individuals to achieve a major change in the company’s policies and procedures. The way the manager goes about this process is explicated in LMX theory.

In summary, LMX theory tells us to be aware of how we relate to our followers. It tells us to be sensitive to whether some followers receive special attention and some followers do not. In addition, it tells us to be fair to all followers and allow each of them to become as involved in the work of the unit as they want to be. LMX theory tells us to be respectful and to build trusting relationships with all of our followers, recognizing that each follower is unique and wants to relate to us in a special way.

Case Studies

In the following section, three case studies (Cases 7.1, 7.2, and 7.3) are presented to clarify how LMX theory can be applied to various group set- tings. The first case is about the creative director at an advertising agency, the second is about a production manager at a mortgage company, and the third is about the leadership of the manager of a district office of the Social Security Administration. After each case, there are questions that will help you analyze it, using the ideas from LMX theory.

Case 7.1

His Team Gets the Best Assignments

Carly Peters directs the creative department of the advertising agency of Mills, Smith, & Peters. The agency has about 100 employees, 20 of whom work for Carly in the creative department. Typically, the agency maintains 10 major accounts and a number of smaller accounts. It has a reputation for being one of the best advertising and public relations agencies in the country.

In the creative department, there are four major account teams. Each is led by an associate creative director, who reports directly to Carly. In addition, each team has a copywriter, an art director, and a production artist. These four account teams are headed by Jack, Terri, Julie, and Sarah.

Jack and his team get along really well with Carly, and they have done excellent work for their clients at the agency. Of all the teams, Jack’s team is the most creative and talented and the most willing to go the extra mile for Carly. As a result, when Carly has to showcase accounts to upper management, she often uses the work of Jack’s team. Jack and his team members are comfortable confiding in Carly and she in them. Carly is not afraid to allocate extra resources to Jack’s team or to give them free rein on their accounts because they always come through for her.

Terri’s team also performs well for the agency, but Terri is unhappy with how Carly treats her team. She feels that Carly is not fair because she favors Jack’s team. For example, Terri’s team was counseled out of pursuing an ad campaign because the campaign was too risky, whereas Jack’s group was praised for developing a very provocative campaign. Terri feels that Jack’s team is Carly’s pet: His team gets the best assignments, accounts, and budgets. Terri finds it hard to hold back the animosity she feels toward Carly.

Like Terri, Julie is concerned that her team is not in the inner circle, close to Carly. She has noticed repeatedly that Carly favors the other teams. For example, whenever additional people are assigned to team projects, it is always the other teams who get the best writers and art directors. Julie is mystified as to why Carly doesn’t notice her team or try to help it with its work. She feels Carly undervalues her team because Julie knows the quality of her team’s work is indisputable.

Although Sarah agrees with some of Terri’s and Julie’s observations about Carly, she does not feel any antagonism about Carly’s leadership. Sarah has worked for the agency for nearly 10 years, and nothing seems to bother her. Her account teams have never been earthshaking, but they have never been problematic either. Sarah views her team and its work more as a nuts-and-bolts operation in which the team is given an assignment and carries it out. Being in Carly’s inner circle would entail putting in extra time in the evening or on weekends and would create more headaches for Sarah. Therefore, Sarah is happy with her role as it is, and she has little interest in trying to change the way the department works.

Questions

1. Based on the principles of LMX theory, what observations would you make about Carly’s leadership at Mills, Smith, & Peters?

2. Is there an in-group and out-group, and if so, which are they?

3. In what way is Carly’s relationship with the four groups productive or counterproductive to the overall goals of the agency?

4. Do you think Carly should change her approach toward the associate directors? If so, what should she do differently?

Case 7.2

Working Hard at Being Fair

City Mortgage is a medium-size mortgage company that employs about 25 people. Jenny Hernandez, who has been with the company for 10 years, is the production manager who oversees its day-to-day operations.

Reporting to Jenny are loan originators (salespeople), closing officers, mortgage underwriters, and processing and shipping personnel. Jenny is proud of the company and feels as if she has contributed substantially to its steady growth and expansion.

The climate at City Mortgage is very positive. People like to come to work because the office environment is comfortable. They respect each other at the company and show tolerance for those who are different from themselves.

Whereas at many mortgage companies it is common for resentments to build between people who earn different incomes, this is not the case at City Mortgage.

Jenny’s leadership has been instrumental in shaping the success of City Mortgage. Her philosophy stresses listening to employees and then determining how each employee can best contribute to the mission of the company. She makes a point of helping each person explore her or his own talents, and challenges each one to try new things.

At the annual holiday party, Jenny devised an interesting event that symbolizes her leadership style. She bought a large piece of colorful glass and had it cut into 25 pieces and handed out one piece to each person. Then she asked each employee to come forward with the piece of glass and briefly state what he or she liked about City Mortgage and how he or she had contributed to the company in the past year. After the statements were made, the pieces of glass were formed into a cut glass window that hangs in the front lobby of the office. The glass is a reminder of how each individual contributes his or her uniqueness to the overall purpose of the company.

Another characteristic of Jenny’s style is her fairness. She does not want to give anyone the impression that certain people have the inside track, and she goes to great lengths to prevent this from happening. For example, she avoids social lunches because she thinks they foster the perception of favoritism. Similarly, even though her best friend is one of the loan originators, she is seldom seen talking with her, and if she is, it is always about business matters.

Jenny also applies her fairness principle to how information is shared in the office. She does not want anyone to feel as if he or she is out of the loop, so she tries very hard to keep her employees informed on all the matters that could affect them. Much of this she does through her open-door office policy. Jenny does not have a special group of employees with whom she confides her concerns; rather, she shares openly with each of them.

Jenny is very committed to her work at City Mortgage. She works long hours and carries a beeper on the weekend. At this point in her career, her only concern is that she could be burning out.

Questions

1. Based on the LMX model, how would you describe Jenny’s leadership?

2. How do you think the employees at City Mortgage respond to Jenny?

3. If you were asked to follow in Jenny’s footsteps, do you think you could or would want to manage City Mortgage with a similar style?

Case 7.3

Taking on Additional Responsibilities

Jim Madison is manager of a district office for the Social Security Administration. The office serves a community of 200,000 people and has a staff of 30 employees, most of whom work as claim representatives.

The primary work of the office is to provide the public with information about Social Security benefits and to process retirement, survivor, disability, and Medicare claims.

Jim has been the manager of the office for 6 years; during that time, he has made many improvements in the overall operations of the office. People in the community have a favorable view of the office and have few complaints about the services it provides. On the annual survey of community service organizations, the district office receives consistently high marks for overall effectiveness and customer satisfaction.

Almost all of the employees who work for Jim have been employed at the district office for 6 years or more; one employee has been there for 22 years. Although Jim takes pride in knowing all of them personally, he calls on a few of them more frequently than others to help him accomplish his goals.

When it comes to training staff members about new laws affecting claim procedures, Jim relies heavily on two particular claim representatives, Shirley and Patti, both of whom are very knowledgeable and competent. Shirley and Patti view the additional training responsibilities as a challenge. This helps Jim: He does not need to do the job himself or supervise them closely because they are highly respected people within the office, and they have a history of being mature and conscientious about their work. Shirley and Patti like the additional responsibility because it gives them greater recognition and increased benefits from receiving positive job appraisals.

To showcase the office’s services to the community, Jim calls on two other employees, Ted and Jana. Ted and Jana serve as field representatives for the office and give presentations to community organizations about the nature of Social Security and how it serves the citizens of the district. In addition, they speak on local radio stations, answering call-in questions about the various complexities of Social Security benefits.

Although many of the claim people in the office could act as field representatives, Jim typically calls on Ted and Jana because of their willingness to take on the public relations challenge and because of their special capabilities in this area. This is advantageous for Jim for two reasons: First, these people do an outstanding job in representing the office to the public. Second, Jim is a reticent person, and he finds it quite threatening to be in the public eye. Ted and Jana like to take on this additional role because it gives them added prestige and greater freedom. Being a field representative has its perks because field staff can function as their own bosses when they are not in the office; they can set their own schedules and come and go as they please.

A third area in which Jim calls on a few representatives for added effort is in helping him supervise the slower claim representatives, who seem to be continually behind in writing up the case reports of their clients.

When even a few staff members get behind with their work, it affects the entire office operation. To ameliorate this problem, Jim calls on Glenda and Annie, who are both highly talented, to help the slower staff complete their case reports. Although it means taking on more work themselves, Glenda and Annie do it to be kind and to help the office run more smoothly. Other than personal satisfaction, no additional benefits accrue to them for taking on the additional responsibilities.

Overall, the people who work under Jim’s leadership are satisfied with his supervision. There are some who feel that he caters too much to a few special representatives, but most of the staff think Jim is fair and impartial. Even though he depends more on a few, Jim tries very hard to attend to the wants and needs of his entire staff.

Questions

1. From an LMX theory point of view, how would you describe Jim’s relationships with his employees at the district Social Security office?

2. Can you identify an in-group and an out-group?

3. Do you think the trust and respect Jim places in some of his staff are productive or counterproductive? Why?

4. As suggested in the chapter, leadership making recommends that the leader build high-quality relationships with all of the followers. How would you evaluate Jim’s leadership in regards to leadership making? Discuss.

Leadership Instrument

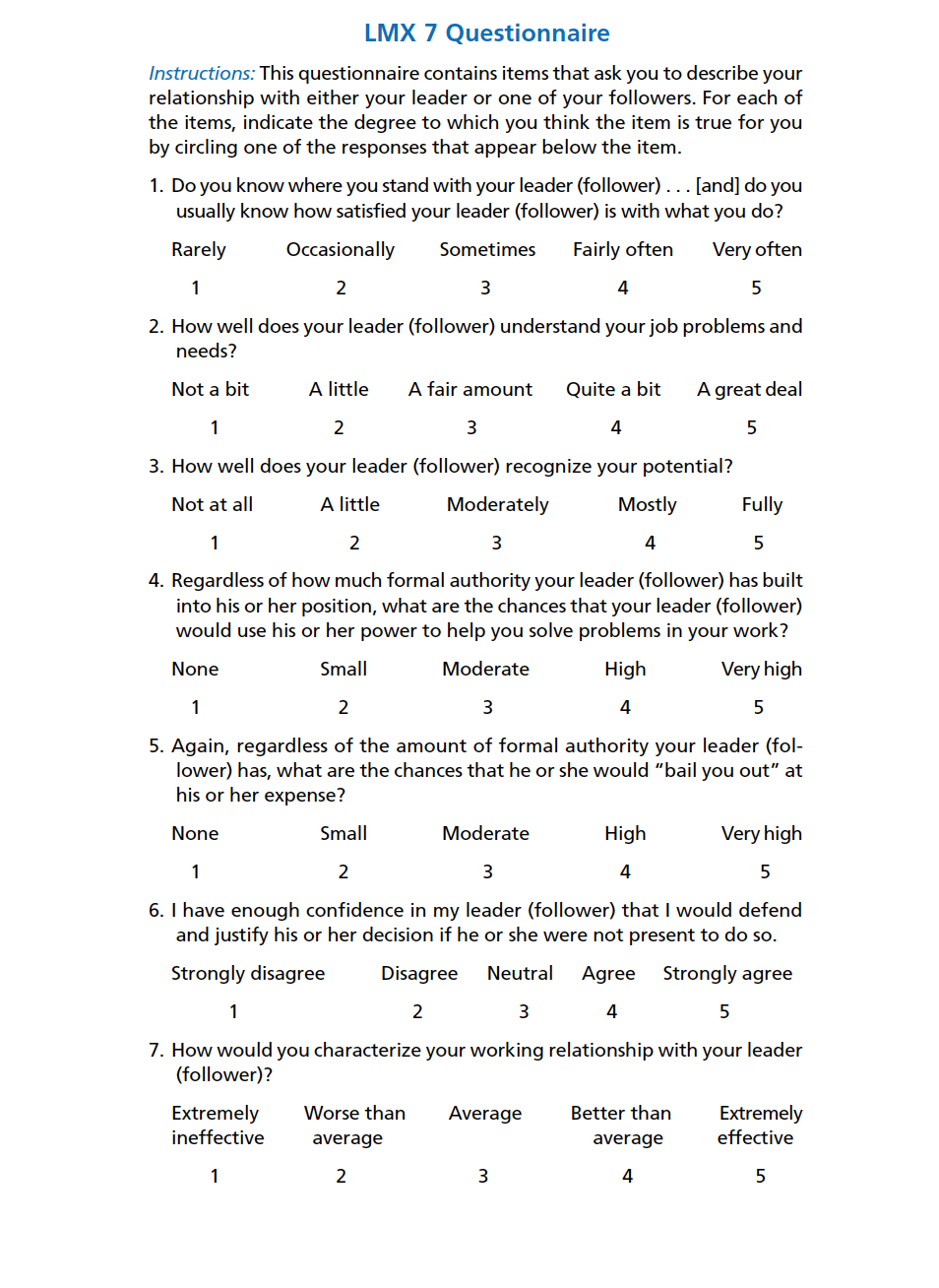

Researchers have used many different questionnaires to study LMX theory. All of them have been designed to measure the quality of the working relationship between leaders and followers. We have chosen to include in this chapter the LMX 7, a seven-item questionnaire that provides a reliable and valid measure of the quality of leader–member exchanges (Graen & Uhl-Bien, 1995).

The LMX 7 is designed to measure three dimensions of leader–member relationships: respect, trust, and obligation. It assesses the degree to which leaders and followers have mutual respect for each other’s capabilities, feel a deepening sense of reciprocal trust, and have a strong sense of obligation to one another. Taken together, these dimensions are the ingredients of strong partnerships.

By completing the LMX 7, you can gain a fuller understanding of how LMX theory works. The score you obtain on the questionnaire reflects the quality of your leader–member relationships, and indicates the degree to which your relationships are characteristic of partnerships, as described in the LMX model.

you can complete the questionnaire both as a leader and as a follower. in the leader role, you would complete the questionnaire multiple times, assessing the quality of the relationships you have with each of your followers. in the follower role, you would complete the questionnaire based on the leaders to whom you report.

scoring interpretation

although the LMX 7 is most commonly used by researchers to explore theoretical questions, you can also use it to analyze your own leadership style. you can interpret your LMX 7 scores using the following guidelines: very high = 30–35, high = 25–29, moderate = 20–24, low = 15–19, and very low = 7–14. scores in the upper ranges indicate stronger, higher- quality leader–member exchanges (e.g., in-group members), whereas scores in the lower ranges indicate exchanges of lesser quality (e.g., out- group members).

Summary

Since it first appeared more than 30 years ago under the title “vertical dyad linkage (VDL) theory,” LMX theory has been and continues to be a much- studied approach to leadership. LMX theory addresses leadership as a pro-cess centered on the interactions between leaders and followers. It makes the leader–member relationship the pivotal concept in the leadership process.

In the early studies of LMX theory, a leader’s relationship to the overall work unit was viewed as a series of vertical dyads, categorized as being of two different types: Leader–member dyads based on expanded role relationships were called the leader’s in-group, and those based on formal job descriptions were called the leader’s out-group. It is believed that followers become in- group members based on how well they get along with the leader and whether they are willing to expand their role responsibilities. Followers who maintain only formal hierarchical relationships with their leader are out-group members. Whereas in-group members receive extra influence, opportunities, and rewards, out-group members receive standard job benefits.

Subsequent studies of LMX theory were directed toward how leader– member exchanges affect organizational performance. Researchers found that high-quality exchanges between leaders and followers produced multiple positive outcomes (e.g., less employee turnover, greater organizational commitment, and more promotions). In general, researchers determined that good leader–member exchanges result in followers feeling better, accomplishing more, and helping the organization prosper.

A select body of LMX research focuses on leadership making, which emphasizes that leaders should try to develop high-quality exchanges with all of their followers. Leadership making develops over time and includes a stranger phase, an acquaintance phase, and a mature partnership phase. By taking on and fulfilling new role responsibilities, followers move through these three phases to develop mature partnerships with their leaders. These partnerships, which are marked by a high degree of mutual trust, respect, and obligation, have positive payoffs for the individuals themselves, and help the organization run more effectively.

There are several positive features to LMX theory. First, LMX theory is a strong descriptive approach that explains how leaders use some followers (in-group members) more than others (out-group members) to accomplish organizational goals effectively. Second, LMX theory is unique in that, unlike other approaches, it makes the leader–member relationship the focal

point of the leadership process. Related to this focus, LMX theory is note- worthy because it directs our attention to the importance of effective com- munication in leader–member relationships. In addition, it reminds us to be evenhanded in how we relate to our followers. Last, LMX theory is sup- ported by a multitude of studies that link high-quality leader–member exchanges to positive organizational outcomes.

There are also negative features in LMX theory. First, the early formulation of LMX theory (VDL theory) runs counter to our principles of fairness and justice in the workplace by suggesting that some members of the work unit receive special attention and others do not. The perceived inequalities created by the use of in-groups can have a devastating impact on the feelings, attitudes, and behavior of out-group members. Second, LMX theory emphasizes the importance of leader–member exchanges but fails to explain the intricacies of how one goes about creating high-quality exchanges. Although the model promotes building trust, respect, and commitment in relationships, it does not fully explicate how this takes place. Third, researchers have not adequately explained the contextual factors that influence LMX relationships. Finally, there are questions about whether the measurement procedures used in LMX research are adequate to fully capture the complexities of the leader–member exchange process.