Textbook Reading: Northouse Chapter 13

Leadership Ethics

Description

This chapter is different from many of the other chapters in this book. Most of the other chapters focus on one unified leadership theory or approach (e.g., trait approach, path–goal theory, or transformational leadership), whereas this chapter is multifaceted and presents a broad set of ethical viewpoints. The chapter is intended not as an “ethical leadership theory,” but rather as a guide to some of the ethical issues that arise in leadership situations.

Probably since our cave-dwelling days, human beings have been concerned with the ethics of our leaders. Our history books are replete with descriptions of good kings and bad kings, great empires and evil empires, and strong presidents and weak presidents. But despite a wealth of biographical accounts of great leaders and their morals, very little research has been published on the theoretical foundations of leadership ethics. There have been many studies on business ethics in general since the early 1970s, but these studies have been only tangentially related to leadership ethics. Even in the literature of management, written primarily for practitioners, there are very few books on leadership ethics. This suggests that theoretical formulations in this area are still in their infancy.

One of the earliest writings that specifically focused on leadership ethics appeared as recently as 1996. It was a set of working papers generated from a small group of leadership scholars, brought together by the W. K. Kellogg Foundation. These scholars examined how leadership theory and practice could be used to build a more caring and just society. The ideas of the Kellogg group are now published in a volume titled Ethics, the Heart of Leadership (Ciulla, 1998).

Interest in the nature of ethical leadership has continued to grow, particularly because of the many recent scandals in corporate America and the political realm. On the academic front, there has also been a strong interest in exploring the nature of ethical leadership (see Aronson, 2001; Ciulla, 2001, 2003; Johnson, 2011; Kanungo, 2001; Price, 2008; Trevino, Brown, &

Hartman, 2003).

Ethics Defined

From the perspective of Western tradition, the development of ethical theory dates back to Plato (427–347 b.c.) and Aristotle (384–322 b.c.). The word ethics has its roots in the Greek word ethos, which translates to “customs,” “conduct,” or “character.” Ethics is concerned with the kinds of values and morals an individual or a society finds desirable or appropriate. Furthermore, ethics is concerned with the virtuousness of individuals and their motives. Ethical theory provides a system of rules or principles that guide us in making decisions about what is right or wrong and good or bad in a particular situation. It provides a basis for understanding what it means to be a morally decent human being.

In regard to leadership, ethics is concerned with what leaders do and who leaders are. It has to do with the nature of leaders’ behavior, and with their virtuousness. In any decision-making situation, ethical issues are either implicitly or explicitly involved. The choices leaders make and how they respond in a given circumstance are informed and directed by their ethics.

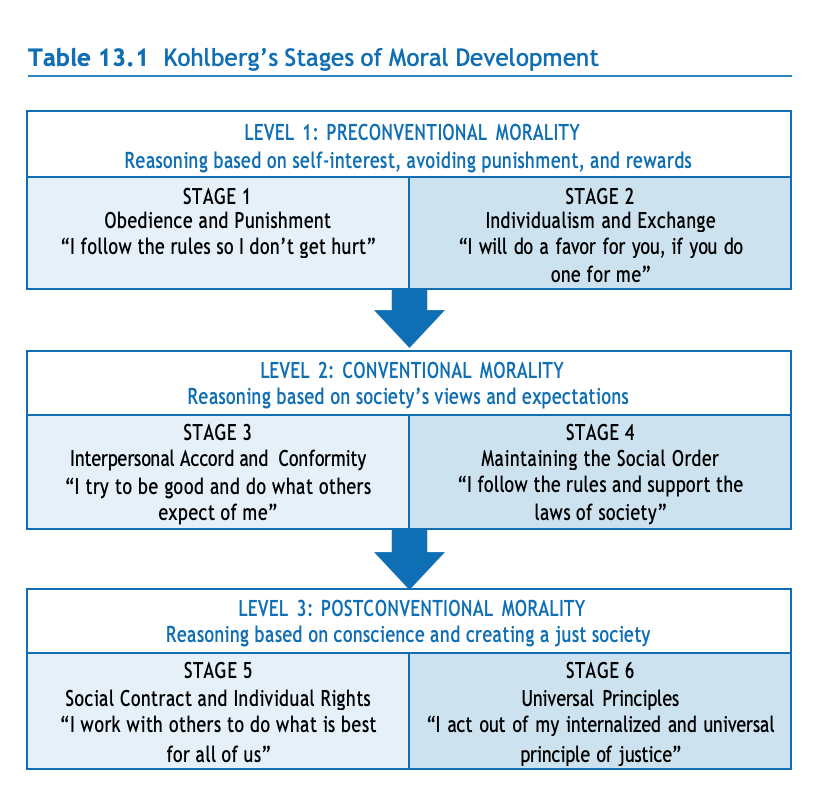

A leader’s choices are also influenced by their moral development. The most widely recognized theory advanced to explain how people think about moral issues is Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. Kohlberg (1984) presented a series of dilemmas (the most famous of which is “the Heinz dilemma”) to groups of young children who he then interviewed about the reasoning behind their choices regarding the dilemmas. From these data he created a classification system of moral reasoning that was divided into six stages: Stage 1—Obedience and Punishment, Stage 2— Individualism and Exchange, Stage 3—Interpersonal Accord and Conformity, Stage 4—Maintaining the Social Order, Stage 5—Social Contract and Individual Rights, and Stage 6—Universal Principles (see Table 13.1). Kohlberg further classified the first two stages as preconventional morality, the second two as conventional morality, and the last two as postconventional morality.

Level 1. Preconventional Morality

When an individual is at the preconventional morality level, he or she tends to judge the morality of an action by its direct consequences. There are two stages that fall within preconventional morality:

Stage 1—Obedience and Punishment. At this stage, the individual is egocentric and sees morality as external to self. Rules are fixed and handed down by authority. Obeying rules is important because it means avoiding punishment. For example, a child reasons it is bad to steal because the consequence will be to go to jail.

Stage 2—Individualism and Exchange. At this stage, the individual makes moral decisions based on self-interest. An action is right if it serves the individual. Everything is relative, so each person is free to do his or her own thing. People do not identify with the values of the community (Crain, 1985) but are willing to exchange favors. For example, an individual might say, “I’ll do a favor for you, if you do a favor for me.”

Level 2. conventional Morality

Those who are at this level judge the morality of actions by comparing them to society’s views and expectations. Authority is internalized but not questioned, and reasoning is based on the norms of the group to which the person belongs. Kohlberg identified two stages at the conventional morality level:

Stage 3—Interpersonal Accord and Conformity. At this stage, the individual makes moral choices based on conforming to the expectations of others and trying to behave like a “good” person. It is important to be “nice” and live up to the community standard of niceness. For example, a student says, “I am not going to cheat because that is not what a good student does.”

Stage 4—Maintaining the Social Order. At this stage, the individual makes moral decisions in ways that show concern for society as a whole. In order for society to function, it is important that people obey the laws, respect authority, and support the rules of the community. For example, a person does not run a red light in the middle of the night when no other cars are around because it is important to maintain and support the traffic laws of the community.

Level 3. postconventional Morality

At this level of morality, also known as the principled level, individuals have developed their own personal set of ethics and morals that guide their behavior. Postconventional moralists live by their own ethical principles—principles that typically include such basic human rights as life, liberty, and justice. There are two stages that Kohlberg identified as part of the postconventional morality level:

Stage 5—Social Contract and Individual Rights. At this stage, the individual makes moral decisions based on a social contract and his or her views on what a good society should be like. A good society supports values such as liberty and life, and fair procedures for changing laws (Crain, 1985), but recognizes that groups have different opinions and values. Societal laws are important, but people need to agree on them. For example, if a boy is dying of cancer and his parents do not have money to pay for his treatment, the state should step in and pay for it.

Stage 6—Universal Principles. At this stage, the individual’s moral reasoning is based on internalized universal principles of justice that apply to everyone. Decisions that are made need to respect the viewpoints of all parties involved. People follow their internal rules of fairness, even if they conflict with laws. An example of this stage would be a civil rights activist who believes a com- mitment to justice requires a willingness to disobey unjust laws.

Kohlberg’s model of moral development has been criticized for focusing exclusively on justice values, for being sex-biased since it is derived from an all-male sample, for being culturally biased since it is based on a sample from an individualist culture, and for advocating a postconventional morality where people place their own principles above those of the law or society (Crain, 1985). Regardless of these criticisms, this model is seminal to developing an understanding of what forms the basis for individuals’ ethical leadership.

Ethical Theories

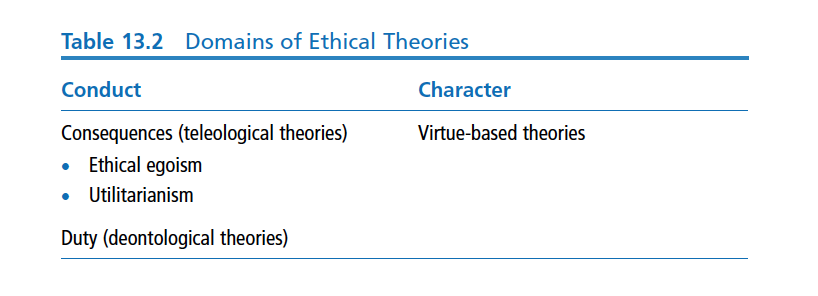

For the purposes of studying ethics and leadership, ethical theories can be thought of as falling within two broad domains: theories about leaders’ conduct and theories about leaders’ character (Table 13.2). Stated another way, ethical theories when applied to leadership are about both the actions of leaders and who they are as people. Throughout the chapter, our discussions about ethics and leadership will always fall within one of these two domains: conduct or character.

Ethical theories that deal with the conduct of leaders are in turn divided into two kinds: theories that stress the consequences of leaders’ actions and those that emphasize the duty or rules governing leaders’ actions (see Table 13.2). Teleological theories, from the Greek word telos, meaning “ends” or “purposes,” try to answer questions about right and wrong by focusing on whether a person’s conduct will produce desirable consequences. From the

teleological perspective, the question “What is right?” is answered by looking at results or outcomes. In effect, the consequences of an individual’s actions determine the goodness or badness of a particular behavior.

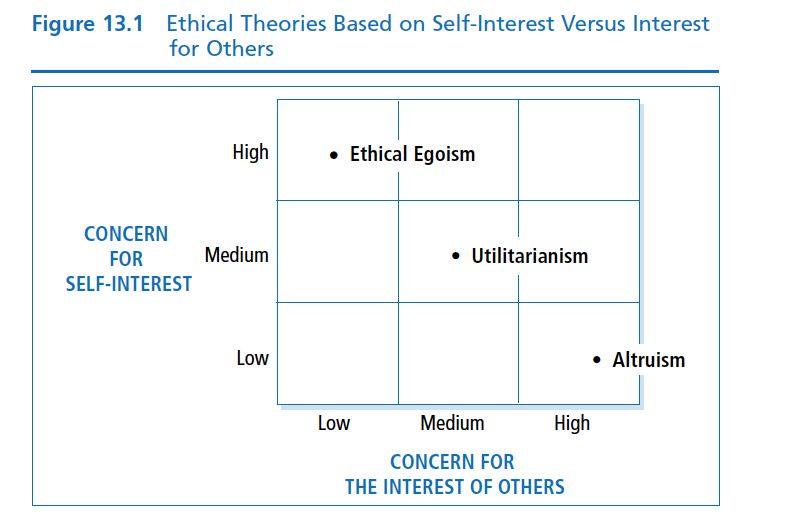

In assessing consequences, there are three different approaches to making decisions regarding moral conduct (Figure 13.1): ethical egoism, utilitarianism, and altruism. Ethical egoism states that a person should act so as to create the greatest good for her- or himself. A leader with this orientation would take a job or career that she or he selfishly enjoys (Avolio & Locke, 2002). Self-interest is an ethical stance closely related to transactional leadership theories (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999). Ethical egoism is common in some business contexts in which a company and its employees make decisions to achieve its goal of maximizing profits. For example, a midlevel, upward-aspiring manager who wants her team to be the best in the company could be described as acting out of ethical egoism.

A second teleological approach, utilitarianism, states that we should behave so as to create the greatest good for the greatest number. From this viewpoint, the morally correct action is the action that maximizes social benefits while minimizing social costs (Schumann, 2001). When the U.S. government allocates a large part of the federal budget for preventive health care rather than for catastrophic illnesses, it is acting from a utilitarian perspective, putting money where it will have the best result for the largest number of citizens.

Closely related to utilitarianism, and opposite of ethical egoism, is a third teleological approach, altruism. Altruism is an approach that suggests that actions are moral if their primary purpose is to promote the best interests of others. From this perspective, a leader may be called on to act in the interests of others, even when it runs contrary to his or her own self-interests (Bowie, 1991). Authentic transformational leadership (Chapter 8) is based on altru- istic principles (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999; Kanungo & Mendonca, 1996) and altruism is pivotal to exhibiting servant leadership (Chapter 10). The strongest example of altruist ethics can be found in the work of Mother Teresa, who devoted her life to helping the poor.

Quite different from looking at which actions will produce which outcomes, deontological theory is derived from the Greek word deos, which means “duty.” Whether a given action is ethical rests not only with its consequences (teleo- logical), but also with whether the action itself is good. Telling the truth, keep- ing promises, being fair, and respecting others are all examples of actions that are inherently good, independent of the consequences. The deontological per- spective focuses on the actions of the leader and his or her moral obligations and responsibilities to do the right thing. A leader’s actions are moral if the leader has a moral right to do them, if the actions do not infringe on others’ rights, and if the actions further the moral rights of others (Schumann, 2001).

In the late 1990s, the president of the United States, Bill Clinton, was brought before Congress for misrepresenting under oath an affair he had maintained with a White House intern. For his actions, he was impeached by the U.S. House of Representatives, but then was acquitted by the U.S. Senate. At one point during the long ordeal, the president appeared on national television and, in what is now a famous speech, declared his innocence. Because subsequent hearings provided information that suggested that he may have lied during this television speech, many Americans felt President Clinton had violated his duty and responsibility (as a person, leader, and president) to tell the truth. From a deontological perspective, it could be said that he failed his ethical responsibility to do the right thing—to tell the truth.

Whereas teleological and deontological theories approach ethics by looking at the behavior or conduct of a leader, a second set of theories approaches ethics from the viewpoint of a leader’s character (see Table 13.2). These theories are called virtue-based theories; they focus on who leaders are as people. In this perspective, virtues are rooted in the heart of the individual and in the individual’s disposition (Pojman, 1995). Furthermore, it is believed that virtues and moral abilities are not innate but can be acquired and learned through practice. People can be taught by their families and communities to be morally appropriate human beings.

With their origin traced back in the Western tradition to the ancient Greeks and the works of Plato and Aristotle, virtue theories are experiencing a resurgence in popularity. The Greek term associated with these theories is aretaic, which means “excellence” or “virtue.” Consistent with Aristotle, current advocates of virtue-based theory stress that more attention should be given to the development and training of moral values (Velasquez, 1992). Rather than telling people what to do, attention should be directed toward telling people what to be, or helping them to become more virtuous.

What, then, are the virtues of an ethical person? There are many, all of which seem to be important. Based on the writings of Aristotle, a moral person demonstrates the virtues of courage, temperance, generosity, self-control, honesty, sociability, modesty, fairness, and justice (Velasquez, 1992). For Aristotle, virtues allowed people to live well in communities. Applying ethics to leadership and management, Velasquez has suggested that managers should develop virtues such as perseverance, public-spiritedness, integrity, truthfulness, fidelity, benevolence, and humility.

In essence, virtue-based ethics is about being and becoming a good, worthy human being. Although people can learn and develop good values, this theory maintains that virtues are present in one’s disposition. When practiced over time, from youth to adulthood, good values become habitual, and part of the people themselves. By telling the truth, people become truthful; by giving to the poor, people become benevolent; by being fair to others, people become just. Our virtues are derived from our actions, and our actions manifest our virtues (Frankena, 1973; Pojman, 1995).

Centrality of Ethics to Leadership

As discussed in Chapter 1, leadership is a process whereby the leader influences others to reach a common goal. The influence dimension of leadership requires the leader to have an impact on the lives of those being led. To make a change in other people carries with it an enormous ethical burden and responsibility. Because leaders usually have more power and control than followers, they also have more responsibility to be sensitive to how their leadership affects followers’ lives.

Whether in group work, organizational pursuits, or community projects, leaders engage followers and utilize them in their efforts to reach common goals. In all these situations, leaders have the ethical responsibility to treat followers with dignity and respect—as human beings with unique identities.

This “respect for people” demands that leaders be sensitive to followers’ own interests, needs, and conscientious concerns (Beauchamp & Bowie, 1988). Although all of us have an ethical responsibility to treat other people as unique human beings, leaders have a special responsibility, because the nature of their leadership puts them in a special position in which they have a greater opportunity to influence others in significant ways.

Ethics is central to leadership, and leaders help to establish and reinforce organizational values. Every leader has a distinct philosophy and point of view. “All leaders have an agenda, a series of beliefs, proposals, values, ideas, and issues that they wish to ‘put on the table’” (Gini, 1998, p. 36). The values promoted by the leader have a significant impact on the values exhibited by the organization (see Carlson & Perrewe, 1995; Schminke, Ambrose, & Noel, 1997; Trevino, 1986). Again, because of their influence, leaders play a major role in establishing the ethical climate of their organizations.

In short, ethics is central to leadership because of the nature of the process of influence, the need to engage followers in accomplishing mutual goals, and the impact leaders have on the organization’s values.

The following section provides a discussion of some of the work of prominent leadership scholars who have addressed issues related to ethics and leadership. Although many additional viewpoints exist, those presented are representative of the predominant thinking in the area of ethics and leadership today.

Heifetz’s Perspective on Ethical Leadership

Based on his work as a psychiatrist and his observations and analysis of many world leaders (e.g., President Lyndon Johnson, Mohandas Gandhi, and Margaret Sanger), Ronald Heifetz (1994) has formulated a unique approach to ethical leadership. His approach emphasizes how leaders help followers to confront conflict and to address conflict by effecting changes. Heifetz’s perspective is related to ethical leadership because it deals with values: the values of workers and the values of the organizations and communities in which they work. According to Heifetz, leadership involves the use of authority to help followers deal with the conflicting values that emerge in rapidly changing work environments and social cultures. It is an ethical perspective because it speaks directly to the values of workers.

For Heifetz (1994), leaders must use authority to mobilize people to face tough issues. As was discussed in the chapter on adaptive leadership (Chapter 11), it is up to the leader to provide a “holding environment” in which there is trust, nurturance, and empathy. In a supportive context, followers can feel safe to confront hard problems. Specifically, leaders use authority to get people to pay attention to the issues, to act as a reality test regarding information, to manage and frame issues, to orchestrate conflicting perspectives, and to facilitate decision making (Heifetz, 1994, p. 113). The leader’s duties are to assist the follower in struggling with change and personal growth.

Burns’s Perspective on Ethical Leadership

As discussed in Chapter 8, Burns’s theory of transformational leadership places a strong emphasis on followers’ needs, values, and morals. Transformational leadership involves attempts by leaders to move followers to higher standards of moral responsibility. This emphasis sets transformational leadership apart from most other approaches to leadership because it clearly states that leadership has a moral dimension (see Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999).

Similar to that of Heifetz, Burns’s (1978) perspective argues that it is important for leaders to engage themselves with followers and help them in their personal struggles regarding conflicting values. The resulting connection raises the level of morality in both the leader and the follower.

The origins of Burns’s position on leadership ethics are rooted in the works of such writers as Abraham Maslow, Milton Rokeach, and Lawrence Kohlberg (Ciulla, 1998). The influence of these writers can be seen in how Burns emphasizes the leader’s role in attending to the personal motivations and moral development of the follower. For Burns, it is the responsibility of the leader to help followers assess their own values and needs in order to raise them to a higher level of functioning, to a level that will stress values such as liberty, justice, and equality (Ciulla, 1998).

Burns’s position on leadership as a morally uplifting process has not been without its critics. It has raised many questions: How do you choose what a better set of moral values is? Who is to say that some decisions represent higher moral ground than others? If leadership, by definition, entails raising individual moral functioning, does this mean that the leadership of corrupt leaders is not actually leadership? Notwithstanding these very legitimate questions, Burns’s perspective is unique in that it makes ethics the central characteristic of the leadership process. His writing has placed ethics at the forefront of scholarly discussions of what leadership means and how leadership should be carried out.

The Dark Side of Leadership

Although Burns (1978) placed ethics at the core of leadership, there still exists a dark side of leadership that exemplifies leadership that is unethical and destructive. It is what we defined in Chapter 8 (“Transformational Leadership”) as pseudotransformational leadership. The dark side of leadership is the destructive and toxic side of leadership in that a leader uses leadership for personal ends. Lipman-Blumen (2005) suggests that toxic leaders are characterized by destructive behaviors such as leaving their followers worse off than they found them, violating the basic human rights of others, and playing to their basest fears. Furthermore, Lipman-Blumen identifies many dysfunctional personal characteristics destructive leaders demonstrate including lack of integrity, insatiable ambition, arrogance, and reckless dis- regard for their actions. The same characteristics and behaviors that distinguish leaders as special can also be used by leaders to produce disastrous outcomes (Conger, 1990). Because researchers have been focused on the positive attributes and outcomes of effective leadership, until recently, there has been little attention paid to the dark side of leadership. Nevertheless, it is important to understand that it exists.

In a meta-analysis of 57 studies of destructive leadership and its outcomes, Schyns and Schilling (2013) found a strong relationship between destructive leadership and negative attitudes in followers toward the leader. Destructive leadership is also negatively related to followers’ attitudes toward their jobs and toward their organization as a whole. Furthermore, Schyns and Schilling found it closely related to negative affectivity and to the experience of occupational stress.

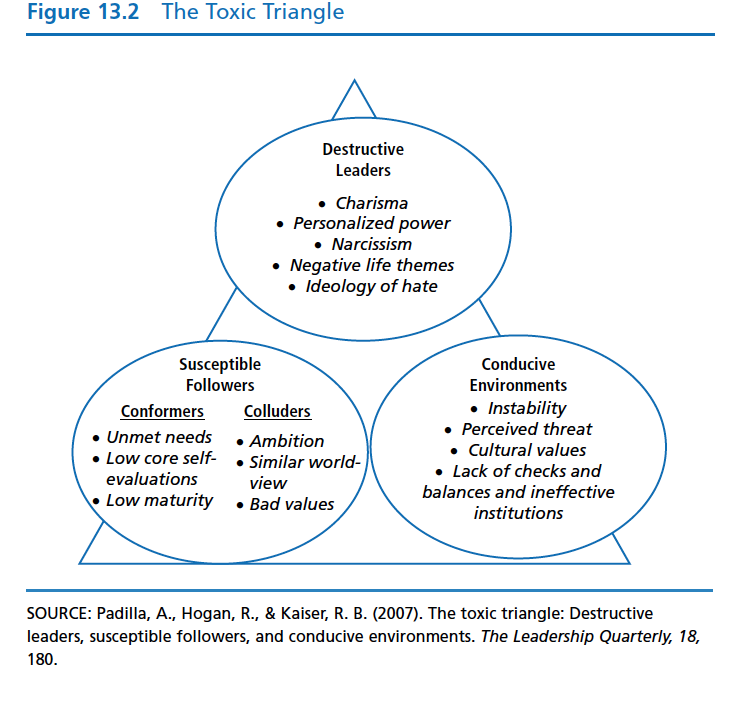

In an attempt to more clearly define destructive leadership, Padilla, Hogan, and Kaiser (2007) developed the concept of a toxic triangle that focuses on the influences of destructive leaders, susceptible followers, and conducive environments (see Figure 13.2). As shown in the model, destructive leaders are characterized by having charisma and a need to use power and coercion for personal gains. They are also narcissistic and often attention-getting and self-absorbed. Destructive leaders often have negative life stories that can be traced to traumatic childhood events. Perhaps from self-hatred, they often express an ideology of hate in their rhetoric and worldview.

As illustrated in Figure 13.2, destructive leadership also incorporates susceptible followers who have been characterized as conformers and colluders. Conformers go along with destructive leaders to satisfy unmet needs such as emptiness, alienation, or need for community. These followers have low self- esteem and identify with charismatic leaders in an attempt to become more

desirable. Because they are psychologically immature, conformers more easily go along with authority and engage in destructive activity. On the other hand, colluders may respond to destructive leaders because they are ambitious, desire status, or see an opportunity to profit. Colluders may also go along because they identify with the leader’s beliefs and values, which may be unsocialized such as greed and selfishness.

Finally, the toxic triangle illustrates that destructive leadership includes a conducive environment. When the environment is unstable, the leader is often granted more authority to assert radical change. When there is a perceived threat, followers often accept assertive leadership. People are attracted to leaders who will stand up to the threats they feel in the environment. Destructive leaders who express compatible cultural values with followers are more likely to succeed. For example, cultures high on collectiveness would prefer a leader who promotes community and group identity. Destructive leadership will also thrive when the checks and balances of the organization are weak and the rules of the institution are ineffective.

Although research on the dark side of leadership has been limited, it is an area critical to our understanding of leadership that is unethical. Clearly, there is a need for the development of models, theories, and assessment instruments about the process of destructive leadership.

Principles of Ethical Leadership

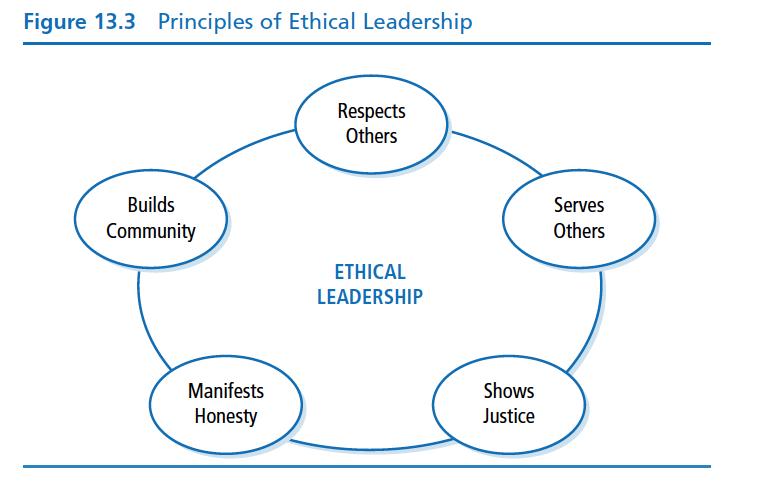

In this section, we turn to a discussion of five principles of ethical leadership, the origins of which can be traced back to Aristotle. The importance of these principles has been discussed in a variety of disciplines, including biomedical ethics (Beauchamp & Childress, 1994), business ethics (Beauchamp & Bowie, 1988), counseling psychology (Kitchener, 1984), and leadership edu- cation (Komives, Lucas, & McMahon, 1998), to name a few. Although not inclusive, these principles provide a foundation for the development of sound ethical leadership: respect, service, justice, honesty, and community (Figure 13.3).

Ethical Leaders respect others

Philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804) argued that it is our duty to treat others with respect. To do so means always to treat others as ends in themselves and never as means to ends. As Beauchamp and Bowie (1988,

p. 37) pointed out, “Persons must be treated as having their own autono- mously established goals and must never be treated purely as the means to another’s personal goals.” These writers then suggested that treating others as ends rather than as means requires that we treat other people’s decisions and values with respect: Failing to do so would signify that we were treat- ing them as a means to our own ends.

Leaders who respect others also allow them to be themselves, with creative wants and desires. They approach other people with a sense of their uncon- ditional worth and valuable individual differences (Kitchener, 1984). Respect includes giving credence to others’ ideas and confirming them as human beings. At times, it may require that leaders defer to others. As Burns (1978) suggested, leaders should nurture followers in becoming aware of their own needs, values, and purposes, and assist followers in integrating these with the leader’s needs, values, and purposes.

Respect for others is a complex ethic that is similar to but goes deeper than the kind of respect that parents teach little children. Respect means that a leader listens closely to followers, is empathic, and is tolerant of opposing points of view. It means treating followers in ways that confirm their beliefs, attitudes, and values. When a leader exhibits respect to followers, followers can feel competent about their work. In short, leaders who show respect treat others as worthy human beings.

Ethical Leaders serve others

Earlier in this chapter, we contrasted two ethical theories, one based on a concern for self (ethical egoism) and another based on the interests of others (ethical altruism). The service principle clearly is an example of altruism. Leaders who serve are altruistic: They place their followers’ welfare foremost in their plans. In the workplace, altruistic service behavior can be observed in activities such as mentoring, empowerment behaviors, team building, and citizenship behaviors, to name a few (Kanungo & Mendonca, 1996).

The leader’s ethical responsibility to serve others is very similar to the ethical principle in health care of beneficence. Beneficence is derived from the Hippocratic tradition, which holds that health professionals ought to make choices that benefit patients. In a general way, beneficence asserts that providers have a duty to help others pursue their own legitimate interests and goals (Beauchamp & Childress, 1994). Like health professionals, ethical leaders have a responsibility to attend to others, be of service to them, and make decisions pertaining to them that are beneficial and not harmful to their welfare.

In the past decade, the service principle has received a great deal of emphasis in the leadership literature. It is clearly evident in the writings of Block (1993), Covey (1990), De Pree (1989), Gilligan (1982), and Kouzes and Posner (1995), all of whom maintained that attending to others is the primary building block of moral leadership. Further emphasis on service can be observed in the work of Senge (1990) in his well-recognized writing on learning organizations. Senge contended that one of the important tasks of leaders in learning organizations is to be the steward (servant) of the vision within the organization. Being a steward means clarifying and nurturing a vision that is greater than oneself. This means not being self-centered, but rather integrating one’s self or vision with that of others in the organization. Effective leaders see their own personal vision as an important part of something larger than themselves—a part of the organization and the community at large.

The idea of leaders serving others was more deeply explored by Robert Greenleaf (1970, 1977), who developed the servant leadership approach. Servant leadership, which is explored in depth in Chapter 10, has strong altruistic ethical overtones in how it emphasizes that leaders should be attentive to the concerns of their followers and should take care of them and nurture them. In addition, Greenleaf argues that the servant leader has a social responsibility to be concerned with the have-nots and should strive to remove inequalities and social injustices. Greenleaf places a great deal of emphasis on listening, empathy, and unconditional acceptance of others.

In short, whether it is Greenleaf ’s notion of waiting on the have-nots or Senge’s notion of giving oneself to a larger purpose, the idea behind service is contributing to the greater good of others. Recently, the idea of serving the “greater good” has found an unusual following in the business world. In 2009, 20% of the graduating class of the Harvard Business School, considered to be one of the premier schools producing today’s business leaders, took an oath pledging that they will act responsibly and ethically, and refrain from advancing their own ambitions at the expense of others. Similarly, Columbia Business School requires all students to pledge to an honor code requiring they adhere to truth, integrity, and respect (Wayne, 2009). In practicing the principle of service, these and other ethical leaders must be willing to be follower centered, must place others’ interests foremost in their work, and must act in ways that will benefit others.

Ethical Leaders Are Just

Ethical leaders are concerned about issues of fairness and justice. They make it a top priority to treat all of their followers in an equal manner. Justice demands that leaders place issues of fairness at the center of their decision making. As a rule, no one should receive special treatment or special consideration except when his or her particular situation demands it. When individuals are treated differently, the grounds for different treatment must be clear and reasonable, and must be based on moral values.

For example, many of us can remember being involved with some type of athletic team when we were growing up. The coaches we liked were those we thought were fair with us. No matter what, we did not want the coach to treat anyone differently from the rest. When someone came late to practice with a poor excuse, we wanted that person disciplined just as we would have been disciplined. If a player had a personal problem and needed a break, we wanted the coach to give it, just as we would have been given a break. Without question, the good coaches were those who never had favorites and who made a point of playing everyone on the team. In essence, what we wanted was that our coach be fair and just.

When resources and rewards or punishments are distributed to employees, the leader plays a major role. The rules that are used and how they are applied say a great deal about whether the leader is concerned about justice and how he or she approaches issues of fairness.

Rawls (1971) stated that a concern with issues of fairness is necessary for all people who are cooperating together to promote their common interests. It is similar to the ethic of reciprocity, otherwise known as the Golden Rule— “Do unto others as you would have them do unto you”—variations of which have appeared in many different cultures throughout the ages. If we expect fairness from others in how they treat us, then we should treat others fairly in our dealings with them. Issues of fairness become problematic because there is always a limit on goods and resources, and there is often competition for the limited things available. Because of the real or perceived scarcity of resources, conflicts often occur between individuals about fair methods of distribution. It is important for leaders to clearly establish the rules for dis- tributing rewards. The nature of these rules says a lot about the ethical underpinnings of the leader and the organization.

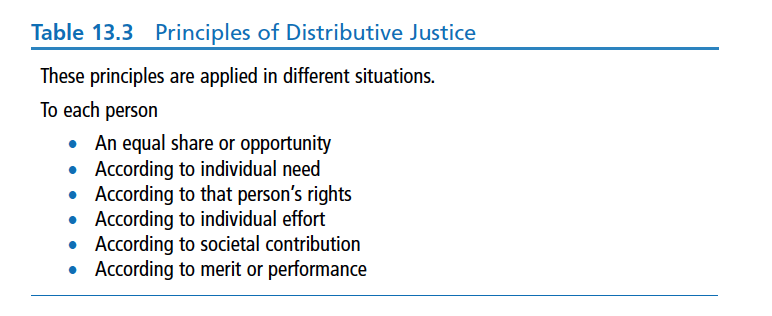

Beauchamp and Bowie (1988) outlined several of the common principles that serve as guides for leaders in distributing the benefits and burdens fairly in an organization (Table 13.3). Although not inclusive, these principles point to the reasoning behind why leaders choose to distribute things as they do in organizations. In a given situation, a leader may use a single principle or a combination of several principles in treating followers.

To illustrate the principles described in Table 13.3, consider the following hypothetical example: You are the owner of a small trucking company that employs 50 drivers. You have just opened a new route, and it promises to be one that pays well and has an ideal schedule. Only one driver can be assigned to the route, but seven drivers have applied for it. Each driver wants an equal opportunity to get the route. One of the drivers recently lost his wife to breast cancer and is struggling to care for three young children (individual need). Two of the drivers are minorities, and one of them feels strongly that he has a right to the job. One of the drivers has logged more driving hours for three consecutive years, and she feels her effort makes her the logical candidate for the new route. One of the drivers serves on the National Transportation Safety Board and has a 20-year accident-free driving record (societal contri- bution). Two drivers have been with the company since its inception, and their performance has been meritorious year after year.

As the owner of the company, your challenge is to assign the new route in a fair way. Although many other factors could influence your decision (e.g., seniority, wage rate, or employee health), the principles described in Table 13.3 provide guidelines for deciding who is to get the new route.

Ethical Leaders Are Honest

When we were children, grown-ups often told us we must “never tell a lie.” To be good meant we must be truthful. For leaders the lesson is the same: To be a good leader, one must be honest.

The importance of being honest can be understood more clearly when we consider the opposite of honesty: dishonesty (see Jaksa & Pritchard, 1988). Dishonesty is a form of lying, a way of misrepresenting reality. Dishonesty may bring with it many objectionable outcomes; foremost among those outcomes is the distrust it creates. When leaders are not honest, others come to see them as undependable and unreliable. People lose faith in what leaders say and stand for, and their respect for leaders is diminished. As a result, the leader’s impact is compromised because others no longer trust and believe in the leader.

When we relate to others, dishonesty also has a negative impact. It puts a strain on how people are connected to each other. When we lie to others, we are in essence saying that we are willing to manipulate the relationship on our own terms. We are saying that we do not trust the other person in the relationship to be able to deal with information we have. In reality, we are putting ourselves ahead of the relationship by saying that we know what is best for the relationship. The long-term effect of this type of behavior is that it weakens relationships. Even when used with good intentions, dishonesty contributes to the breakdown of relationships.

But being honest is not just about telling the truth. It has to do with being open with others and representing reality as fully and completely as possible. This is not an easy task, however, because there are times when telling the complete truth can be destructive or counterproductive. The challenge for leaders is to strike a balance between being open and candid while monitoring what is appropriate to disclose in a particular situation. Many times, there are organizational constraints that prevent leaders from disclosing information to followers. It is important for leaders to be authentic, but it is also essential that they be sensitive to the attitudes and feelings of others. Honest leadership involves a wide set of behaviors.

Dalla Costa (1998) made the point clearly in his book, The Ethical Imperative, that being honest means more than not deceiving. For leaders in organizations, being honest means, “Do not promise what you can’t deliver, do not misrepresent, do not hide behind spin-doctored evasions, do not suppress obligations, do not evade accountability, do not accept that the ‘survival of the fittest’ pressures of business release any of us from the responsibility to respect another’s dignity and humanity” (p. 164). In addition, Dalla Costa suggested that it is imperative that organizations recognize and acknowledge the necessity of honesty and reward honest behavior within the organization.

Ethical Leaders Build community

In Chapter 1, we defined leadership as a process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal. This definition has a clear ethical dimension because it refers to a common goal. A common goal requires that the leader and followers agree on the direction to be taken by the group. Leaders need to take into account their own and followers’ purposes while working toward goals that are suitable for both of them. This factor, concern for others, is the distinctive feature that delineates authentic transformational leaders from pseudotransformational leaders (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999) (for more on pseudotransformational leadership see page 163 in Chapter 8). Concern for the common good means that leaders cannot impose their will on others. They need to search for goals that are compat- ible with everyone.

Burns (1978) placed this idea at the center of his theory on transformational leadership. A transformational leader tries to move the group toward a common good that is beneficial for both the leaders and the followers. In moving toward mutual goals, both the leader and the followers are changed. It is this feature that makes Burns’s theory unique. For Burns, leadership has to be grounded in the leader–follower relationship. It cannot be controlled by the leader, such as Hitler’s influence in Germany. Hitler coerced people to meet his own agenda and followed goals that did not advance the goodness of humankind.

An ethical leader takes into account the purposes of everyone involved in the group and is attentive to the interests of the community and the culture. Such a leader demonstrates an ethic of caring toward others (Gilligan, 1982) and does not force others or ignore the intentions of others (Bass & Steidlmeier, 1999).

Rost (1991) went a step farther and suggested that ethical leadership demands attention to a civic virtue. By this, he meant that leaders and followers need to attend to more than their own mutually determined goals. They need to attend to the community’s goals and purpose. As Burns (1978,

p. 429) wrote, transformational leaders and followers begin to reach out to wider social collectivities and seek to establish higher and broader moral purposes. Similarly, Greenleaf (1970) argued that building community was a main characteristic of servant leadership. All of our individual and group goals are bound up in the common good and public interest. We need to pay attention to how the changes proposed by a leader and followers will affect the larger organization, the community, and society. An ethical leader is concerned with the common good, in the broadest sense.

Strengths

This chapter discusses a broad set of ideas regarding ethics and leadership. This general field of study has several strengths. First, it provides a body of timely research on ethical issues. There is a high demand for moral leadership in our society today. Beginning with the Nixon administration in the 1970s and continuing through Barack Obama’s administration, people have been insisting on higher levels of moral responsibility from their leaders. At a time when there seems to be a vacuum in ethical leadership, this research offers us some direction on how to think about and practice ethical leadership.

Second, this body of research suggests that ethics ought to be considered as an integral part of the broader domain of leadership. Except for servant, transformational, and authentic leadership, none of the other leadership theories discussed in this book includes ethics as a dimension of the leadership process. This chapter suggests that leadership is not an amoral phenomenon. Leadership is a process of influencing others; it has a moral dimension that distinguishes it from other types of influence, such as coercion or despotic control. Leadership involves values, including showing respect for followers, being fair to others, and building community. It is not a process that we can demonstrate without showing our values. When we influence, we have an effect on others, which means we need to pay attention to our values and our ethics.

Third, this body of research highlights several principles that are important to the development of ethical leadership. The virtues discussed in this research have been around for more than 2,000 years. They are reviewed in this chapter because of their significance for today’s leaders.

Criticisms

Although the area of ethics and leadership has many strengths, it also has some weaknesses. First, it is an area of research in its early stage of development, and therefore lacks a strong body of traditional research findings to substantiate it. As was pointed out at the beginning of the chapter, very little research has been published on the theoretical foundations of leadership ethics. Although many studies have been published on business ethics, these studies have not been directly related to ethical leadership. The dearth of research on leadership ethics makes speculation about the nature of ethical leadership difficult. Until more research studies have been conducted that deal directly with the ethical dimensions of leadership, theoretical formulations about the process will remain tentative.

Another criticism is that leadership ethics today relies primarily on the writings of just a few people who have written essays and texts that are strongly influenced by their personal opinions about the nature of leadership ethics and their view of the world. Although these writings, such as Heifetz’s and Burns’s, have stood the test of time, they have not been tested using traditional quantitative or qualitative research methods. They are primarily descriptive and anecdotal. Therefore, leadership ethics lacks the traditional kind of empirical support that usually accompanies accepted theories of human behavior.

Application

Although issues of morality and leadership are discussed more often in society today, these discussions have not resulted in a large number of programs in training and development designed to teach ethical leadership. Many new programs are oriented toward helping managers become more effective at work and in life in general, but these programs do not directly target the area of ethics and leadership.

Yet the ethics and leadership research in this chapter can be applied to people at all levels of organizations and in all walks of life. At a very minimum, it is crucial to state that leadership involves values, and one cannot be a leader without being aware of and concerned about one’s own values. Because leadership has a moral dimension, being a leader demands awareness on our part of the way our ethics defines our leadership.

Managers and leaders can use the information in this research to better understand themselves and strengthen their own leadership. Ethical theories can remind leaders to ask themselves, “What is the right and fair thing to do?” or “What would a good person do?” Leaders can use the ethical principles described in this research as benchmarks for their own behavior. Do I show respect to others? Do I act with a generous spirit? Do I show honesty and faithfulness to others? Do I serve the community? Finally, we can learn from the overriding theme in this research that the leader–follower relationship is central to ethical leadership. To be an ethical leader, we must be sensitive to the needs of others, treat others in ways that are just, and care for others.

Case Studies

The following section contains three case studies (Cases 13.1, 13.2, and 13.3) in which ethical leadership is needed. Case 13.1 describes a department chair who must choose which student will get a special assignment. Case 13.2 is concerned with one manufacturing company’s unique approach to safety standards. Case 13.3 deals with the ethical issues surrounding how a human resource service company established the pricing for its services. At the end of each case, there are questions that point to the intricacies and complexities of practicing ethical leadership.

Case 13.1Choosing a Research Assistant

Dr. Angi Dirks is the chair of the state university’s organizational psychology department, which has four teaching assistants (TAs). Angi has just found out that she has received a grant for research work over the summer and that it includes money to fund one of the TAs as her research assistant. In Angi’s mind, the top two candidates are Roberto and Michelle, who are both available to work over the summer. Roberto, a foreign student from Venezuela, has gotten very high teaching evaluations and is well liked by the faculty. Roberto needs a summer job to help pay for school since it is too expensive for him to return home for the summer to work. Michelle is also an exceptional graduate student; she is married and doesn’t necessarily need the extra income, but she is going to pursue a PhD, so the extra experience would be beneficial to her future endeavors.

A third teaching assistant, Carson, commutes to school from a town an hour away, where he is helping to take care of his aging grandparents. Carson manages to juggle school, teaching, and his home responsibilities well, carrying a 4.0 GPA in his classwork. Angi knows Carson could use the money, but she is afraid that he has too many other responsibilities to take on the research project over the summer.

As Angi weighs which TA to offer the position, a faculty member approaches her about considering the fourth TA, Analisa. It’s been a tough year with Analisa as a TA. She has complained numerous times to her faculty mentor and to Angi that the other TAs treat her differently, and she thinks it’s because of her race. The student newspaper printed a column she wrote about “being a speck of brown in a campus of white,” in which she expressed her frustration with the predominantly white faculty’s inability to understand the unique perspectives and experiences of minority students. After the column came out, the faculty in the department became wary of working with Analisa, fearing becoming part of the controversy. Their lack of interaction with her made Analisa feel further alienated.

Angi knows that Analisa is a very good researcher and writer, and her skills would be an asset to the project. Analisa’s faculty mentor says that giving the position to her would go a long way to “smooth things over” between faculty and Analisa and make Analisa feel included in the department. Analisa knows about the open position and has expressed interest in it to her faculty mentor, but hasn’t directly talked to Angi. Angi is afraid that by not giving it to Analisa, she may stir up more accusations of ill treatment while at the same time facing accusations from others that she is giving Analisa preferential treatment.

1. Of the four options available to Angi, which is the most ethical?

2. Using the principles of distributive justice, who would Angi choose to become the research assistant?

3. From Heifetz’s perspective, can Angi use this decision to help her department and faculty face a difficult situation? Should she?

4. Do you agree with Burns’s perspective that it is Angi’s responsibility to help followers assess their own values and needs in order to raise them to a higher level that will stress values such as liberty, justice, and equality? If so, how can Angi do that through this situation?

Case 13.2

How Safe Is Safe?

Perfect Plastics Incorporated (PPI) is a small injection molding plastics company that employs 50 people. The company is 10 years old, has a healthy balance sheet, and does about $4 million a year in sales. The company has a good safety record, and the insurance company that has PPI’s liability policy has not had to pay any claims to employees for several years. There have been no major injuries of any kind since the company began.

Tom Griffin, the owner, takes great pride in the interior design and working conditions at PPI. He describes the interior of the plant as being like a hospital compared with his competitors. Order, efficiency, and cleanliness are top priorities at PPI. It is a remarkably well-organized manufacturing company.

PPI has a unique approach to guaranteeing safe working conditions. Each year, management brings in outside consultants from the insurance industry and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to audit

the plant for unsafe conditions. Each year, the inspections reveal a variety of concerns, which are then addressed through new equipment, repairs, and changed workflow designs. Although the inspectors continue to find opportunities for improvement, the overall safety improves each year.

The attorneys for PPI are very opposed to the company’s approach to safety. The lawyers are vehemently against the procedure of having outside auditors. If a lawsuit were to be brought against PPI, the attorneys argue that any previous issues could be used as evidence of a historical pattern and knowledge of unsafe conditions. In effect, the audits that PPI conducts voluntarily could be used by plaintiffs to strengthen a case against the company.

The president and management recognize the potential downside of outside audits, but they point out that the periodic reviews are critical to the ongoing improvement of the safety of everyone in the plant. The purpose of the audits is to make the shop a secure place, and that is what has occurred. Management also points out that PPI employees have responded positively to the audits and to the changes that result.

Questions

1. As a company, would you describe PPI as having an identifiable philosophy of moral values? How do its policies contribute to this philosophy?

2. Which ethical perspective best describes PPI’s approach to safety issues? Would you say PPI takes a utilitarian-, duty-, or virtue-based approach?

3. Regarding safety issues, how does management see its responsibilities toward its employees? How do the attorneys see their responsibilities toward PPI?

4. Why does it appear that the ethics of PPI and its attorneys are in conflict?

Case 13.3

Reexamining a Proposal

After working 10 years as the only minority manager in a large printing company, David Jones decided he wanted to set out on his own. Because of his experience and prior connections, David was confident he could survive in the printing business, but he wondered whether he should buy an existing business or start a new one. As part of his planning, David contacted a professional employer organization (PEO), which had a sterling reputation, to obtain an estimate for human resource services for a startup company. The estimate was to include costs for payroll, benefits, workers’ compensation, and other traditional human resource services. Because David had not yet started his business, the PEO generated a generic quote applicable to a small company in the printing industry. In addition, because the PEO had nothing tangible to quote, it gave David a quote for human resource services that was unusually high.

In the meantime, David found an existing small company that he liked, and he bought it. Then he contacted the PEO to sign a contract for human resource services at the previously quoted price. David was ready to take ownership and begin his new venture. He signed the original contract as presented.

After David signed the contract, the PEO reviewed the earlier proposal in light of the actual figures of the company he had purchased. This review raised many concerns for management. Although the goals of the PEO were to provide high-quality service, be competitive in the marketplace, and make a reasonable profit, the quote it had provided David appeared to be much too high. It was not comparable in any way with the other service contracts the PEO had with other companies of similar size and function.

During the review, it became apparent that several concerns had to be addressed. First, the original estimate made the PEO appear as if it was gouging the client. Although the client had signed the original contract, was it fair to charge such a high price for the proposed services? Would charging such high fees mean that the PEO would lose this client or similar clients in the future? Another concern was related to the PEO’s support of minority businesses. For years, the PEO had prided itself on having strong values about affirmative action and fairness in the workplace, but this contract appeared to actually hurt and to be somewhat unfair to a minority client. Finally, the PEO was concerned with the implications of the contract for the salesperson who drew up the proposal for David. Changing the estimated costs in the proposal would have a significant impact on the salesperson’s commission, which would negatively affect the morale of others in the PEO’s sales area.

After a reexamination of the original proposal, a new contract was drawn up for David’s company with lower estimated costs. Though lower than the original proposal, the new contract remained much higher than the average contract in the printing industry. David willingly signed the new contract.

Questions

1. What role should ethics play in the writing of a proposal such as this? Did the PEO do the ethical thing for David? How much money should the PEO have tried to make? What would you have done if you were part of management at the PEO?

2. From a deontological (duty) perspective and a teleological (consequences) perspective, how would you describe the ethics of the PEO?

3. Based on what the PEO did for David, how would you evaluate the PEO on the ethical principles of respect, service, justice, honesty, and community?

4. How would you assess the ethics of the PEO if you were David? If you were among the PEO management? If you were the salesperson? If you were a member of the printing community?

Leadership Instrument

Ethics and morals often are regarded as very personal, and we resist having others judge us about them. We also resist judging others. Perhaps for this reason, very few questionnaires have been designed to measure ethical leadership. To address this problem, Craig and Gustafson (1998) developed the Perceived Leader Integrity Scale (PLIS), which is based on utilitarian ethical theory. The PLIS attempts to evaluate leaders’ ethics by measuring the degree to which coworkers see them as acting in accordance with rules that would produce the greatest good for the greatest number of people. Craig and Gustafson found PLIS ratings to be strongly and positively related to subordinates’ job satisfaction, and negatively related to their desire to quit their jobs.

Parry and Proctor-Thomson (2002) used the PLIS in a study of 1,354 managers and found that perceived integrity was positively related to transformational leadership. Leaders who were seen as transformational were also seen as having more integrity. In addition, the researchers found that perceived integrity was positively correlated with leader and organizational effectiveness.

By taking the PLIS, you can try to assess the ethical integrity of a leader you know, such as a supervisor or leader of a group or organization of which you are a member. At the same time, the PLIS will allow you to apply the ideas we discussed in the chapter to a real-world setting. By focusing on observers’ impressions, the PLIS represents one way to assess the principle of ethical leadership.

In addition, the PLIS can be used for feedback to employees in organizations and as a part of leadership training and development. Finally, if used as part of an organizational climate survey, the PLIS could be useful as a way of identifying areas in an organization that may need an ethics intervention (Craig & Gustafson, 1998).

Perceived Leader Integrity Scale (PLIS)

Instructions: The following items concern your perceptions of another person’s behavior. circle responses to indicate how well each item describes the person you are rating.

Key: 1 = not at all 2 = Barely 3 = somewhat 4 = Well

|

1. puts his or her personal interests ahead of the organization |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

2. Would risk other people to protect himself or herself in work matters |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

3. Enjoys turning down requests |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

4. deliberately fuels conflict between other people |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

5. Would blackmail an employee if she or he thought she or he could get away with it |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

6. Would deliberately exaggerate people’s mistakes to make them look bad to others |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

7. Would treat some people better if they were of the other sex or belonged to a different ethnic group |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

8. ridicules people for their mistakes |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

9. can be trusted with confidential information |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

10. Would lie to me |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

11. is evil |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

12. is not interested in tasks that don’t bring personal glory or recognition |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

13. Would do things that violate organizational policy and then expect others to cover for him or her |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

14. Would allow someone else to be blamed for his or her mistake |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

15. Would deliberately avoid responding to email, telephone, or other messages to cause problems for someone else |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

16. Would make trouble for someone who got on his or her bad side |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

17. Would engage in sabotage against the organization |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

18. Would deliberately distort what other people say |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

19. is a hypocrite |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

20. is vindictive |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

21. Would try to take credit for other people’s ideas |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

22. Likes to bend the rules |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

23. Would withhold information or constructive feedback because he or she wants someone to fail |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

24. Would spread rumors or gossip to try to hurt people or the organization |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

25. is rude or uncivil to coworkers |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

26. Would try to hurt someone’s career because of a grudge |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

27. shows unfair favoritism toward some people |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

28. Would steal from the organization |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

29. Would falsify records if it would help his or her work situation |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

|

30. has high moral standards |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

scoring

The pLis measures your perceptions of another person’s integrity in an organizational setting. your responses on the pLis indicate the degree to which you see that person’s behavior as ethical.

score the questionnaire by doing the following. First, reverse the scores on items 9 and 30 (i.e., 1 becomes 4, 2 becomes 3, 3 becomes 2, and 4 becomes 1). next, sum the responses on all 30 items. a low score on the questionnaire indicates that you perceive the person you evaluated to be highly ethical. a high score indicates that you perceive that person to be very unethical. The interpretation of what the score represents follows.

scoring interpretation

your score is a measure of your perceptions of another person’s ethical integrity. Based on previous findings (craig & Gustafson, 1998), the following interpretations can be made about your total score:

· 30–32 high ethical: if your score is in this range, it means that you see the person you evaluated as highly ethical. your impression is that the person is very trustworthy and principled.

· 33–45 Moderate ethical: scores in this range mean that you see the person as moderately ethical. your impression is that the person might engage in some unethical behaviors under certain conditions.

· 46–120 Low ethical: scores in this range describe people who are seen as very unethical. your impression is that the person you evaluated does things that are dishonest, unfair, and unprincipled almost any time he or she has the opportunity.

Summary

Although there has been an interest in ethics for thousands of years, very little theoretical research exists on the nature of leadership ethics. This chapter has presented an overview of ethical theories as they apply to the leadership process.

Ethical theory provides a set of principles that guide leaders in making decisions about how to act and how to be morally decent. In the Western tradition, ethical theories typically are divided into two kinds: theories about conduct and theories about character. Theories about conduct emphasize the consequences of leader behavior (teleological approach) or the rules that govern their behavior (deontological approach). Virtue-based theories focus on the character of leaders, and they stress qualities such as courage, honesty, fairness, and fidelity.

Ethics plays a central role in the leadership process. Because leadership involves influence and leaders often have more power than followers, they have an enormous ethical responsibility for how they affect other people. Leaders need to engage followers to accomplish mutual goals; therefore, it is imperative that they treat followers and their ideas with respect and dignity. Leaders also play a major role in establishing the ethical climate in their organization; that role requires leaders to be particularly sensitive to the values and ideals they promote.

Several prominent leadership scholars, including Heifetz, Burns, and Greenleaf, have made unique contributions to our understanding of ethical leadership. The theme common to these authors is an ethic of caring, which pays attention to followers’ needs and the importance of leader–follower relationships.

This chapter suggests that sound ethical leadership is rooted in respect, service, justice, honesty, and community. It is the duty of leaders to treat others with respect—to listen to them closely and be tolerant of opposing points of view. Ethical leaders serve others by being altruistic, placing others’ welfare ahead of their own in an effort to contribute to the common good. Justice requires that leaders place fairness at the center of their decision making, including the challenging task of being fair to the individual while simultaneously being fair to the common interests of the community. Good leaders are honest. They do not lie, nor do they present truth to others in ways that are destructive or counterproductive. Finally, ethical leaders are committed to building community, which includes searching for goals that are compatible with the goals of followers and with society as a whole.

Research on ethics and leadership has several strengths. At a time when the public is demanding higher levels of moral responsibility from its leaders, this research provides some direction in how to think about ethical leadership and how to practice it. In addition, this research reminds us that leadership is a moral process. Scholars should include ethics as an integral part of the leadership studies and research. Third, this area of research describes basic principles that we can use in developing real-world ethical leadership.

On the negative side, this research area of ethical leadership is still in an early stage of development. Few studies have been done that directly address the nature of ethical leadership. As a result, the theoretical formulations about the process remain tentative. Second, this area of research relies on the writings of a few individuals whose work has been primarily descriptive and anecdotal. As a result, the development of theory on leadership ethics lacks the traditional empirical support that usually accompanies theories of human behavior. Despite these weaknesses, the field of ethical leadership is wide open for future research. There remains a strong need for research that can advance our understanding of the role of ethics in the leadership process.