Reading: Capital Budgeting

What

is Capital Budgeting?

•Capital

budgeting is the process in which a business determines and evaluates potential

expenses or investments that are large in nature. These expenditures and

investments include projects such as building a new plant or investing in a

long-term venture. Often times, a prospective project's lifetime cash inflows

and outflows are assessed in order to determine whether the potential returns

generated meet a sufficient target benchmark, also known as "investment

appraisal.“

•Ideally,

businesses should pursue all projects and opportunities that enhance

shareholder value. However, because the amount of capital available at any

given time for new projects is limited, management needs to use capital

budgeting techniques to determine which projects will yield the most return

over an applicable period of time. Various methods of capital budgeting can

include throughput analysis, net present value (NPV), internal rate of return

(IRR), discounted cash flow (DCF) and payback period.

Throughput

Analysis

•Throughput

is measured as the amount of material passing through a system. Throughput

analysis is the most complicated form of capital budgeting analysis, but is

also the most accurate in helping managers decide which projects to pursue.

Under this method, the entire company is considered a single, profit-generating

system.

•

•The

analysis assumes that nearly all costs in the system are operating expenses,

that a company needs to maximize the throughput of the entire system to pay for

expenses, and that the way to maximize profits is to maximize the throughput

passing through a bottleneck operation. A bottleneck is the resource in the

system that requires the longest time in operations. This means that managers

should always place higher consideration on capital budgeting projects that

impact and increase throughput passing though the bottleneck.

•This

does not mean that all other capital budgeting proposals will be rejected,

since there are a multitude of possible investments that can reduce costs

elsewhere in a company, and which are therefore worthy of consideration.

However, throughput is more important than cost reduction, since throughput has

no theoretical upper limit, whereas costs can only be reduced to zero. Given

the greater ultimate impact on profits of throughput over cost reduction, any

non-bottleneck proposal is simply not as important.

Discounted

Cash Flow Analysis

•Any

capital investment involves an initial cash outflow to pay for it, followed by

a mix of cash inflows in the form of revenue, or a decline in existing cash

flows that are caused by expenses incurred. We can lay out this information in

a spreadsheet to show all expected cash flows over the useful life of an

investment, and then apply a discount rate that reduces the cash flows to what

they would be worth at the present date. This calculation is known as net

present value. Net present value is the traditional approach to evaluating

capital proposals, since it is based on a single factor – cash flows – that can

be used to judge any proposal arriving from anywhere in a company.

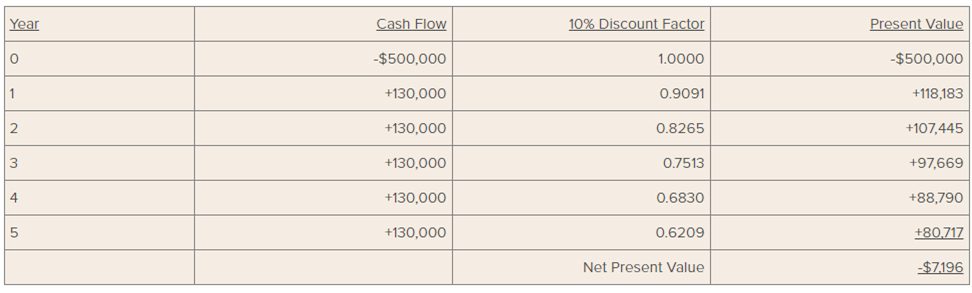

•For

example, ABC Company is planning to acquire an asset that it expects will yield

positive cash flows for the next five years. Its cost of capital is 10%, which

it uses as the discount rate to construct the net present value of the project.

The following table shows the calculation:

Discounted

Cash Flow Analysis

Payback

Analysis

•The

simplest and least accurate evaluation technique is the payback method. This

approach is still heavily used, because it provides a very fast “back of the

envelope” calculation of how soon a company will earn back its investment. This

means that it provides a rough measure of how long a company will have its

investment at risk, before earning back the original amount expended. Thus, it

is a rough measure of risk. There are two ways to calculate the payback period,

which are:

•

•Simplified.

Divide the total amount of an investment by the average resulting cash flow.

This approach can yield an incorrect assessment, because a proposal with cash

flows skewed far into the future can yield a payback period that differs

substantially from when actual payback occurs.

•Manual

calculation. Manually deduct the forecasted positive cash flows from the

initial investment amount, from Year 1 forward, until the investment is paid

back. This method is slower to calculate, but ensures a higher degree of

accuracy.

Net

Present Value

•Net

Present Value (NPV) is the difference between the present value of cash inflows

and the present value of cash outflows. NPV is used in capital budgeting to

analyze the profitability of a projected investment or project.

•A

positive net present value indicates that the projected earnings generated by a

project or investment (in present dollars) exceeds the anticipated costs (also

in present dollars). Generally, an investment with a positive NPV will be a

profitable one and one with a negative NPV will result in a net loss. This

concept is the basis for the Net Present Value Rule, which dictates that the

only investments that should be made are those with positive NPV values.

Internal

Rate of Return

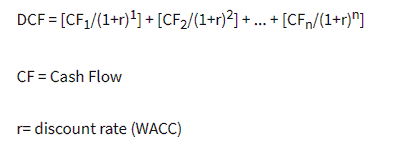

•Internal

rate of return (IRR) is a metric used in capital budgeting measuring the

profitability of potential investments. Internal rate of return is a discount

rate that makes the net present value (NPV) of all cash flows from a particular

project equal to zero. IRR calculations rely on the same formula as NPV does.

•Generally

speaking, the higher a project's internal rate of return, the more desirable it

is to undertake the project. IRR is uniform for investments of varying types

and, as such, IRR can be used to rank multiple prospective projects a firm is

considering on a relatively even basis. Assuming the costs of investment are

equal among the various projects, the project with the highest IRR would

probably be considered the best and undertaken first.

Last modified: Tuesday, August 14, 2018, 8:51 AM